The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of FreightWaves or its affiliates.

On June 11, 2019, FreightWaves ran my Commentary: Key supply chain innovation issues to consider in a world with VUCA. VUCA is an acronym for a state of the world that is simultaneously and increasingly volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous.

Since then, among other things, the world:

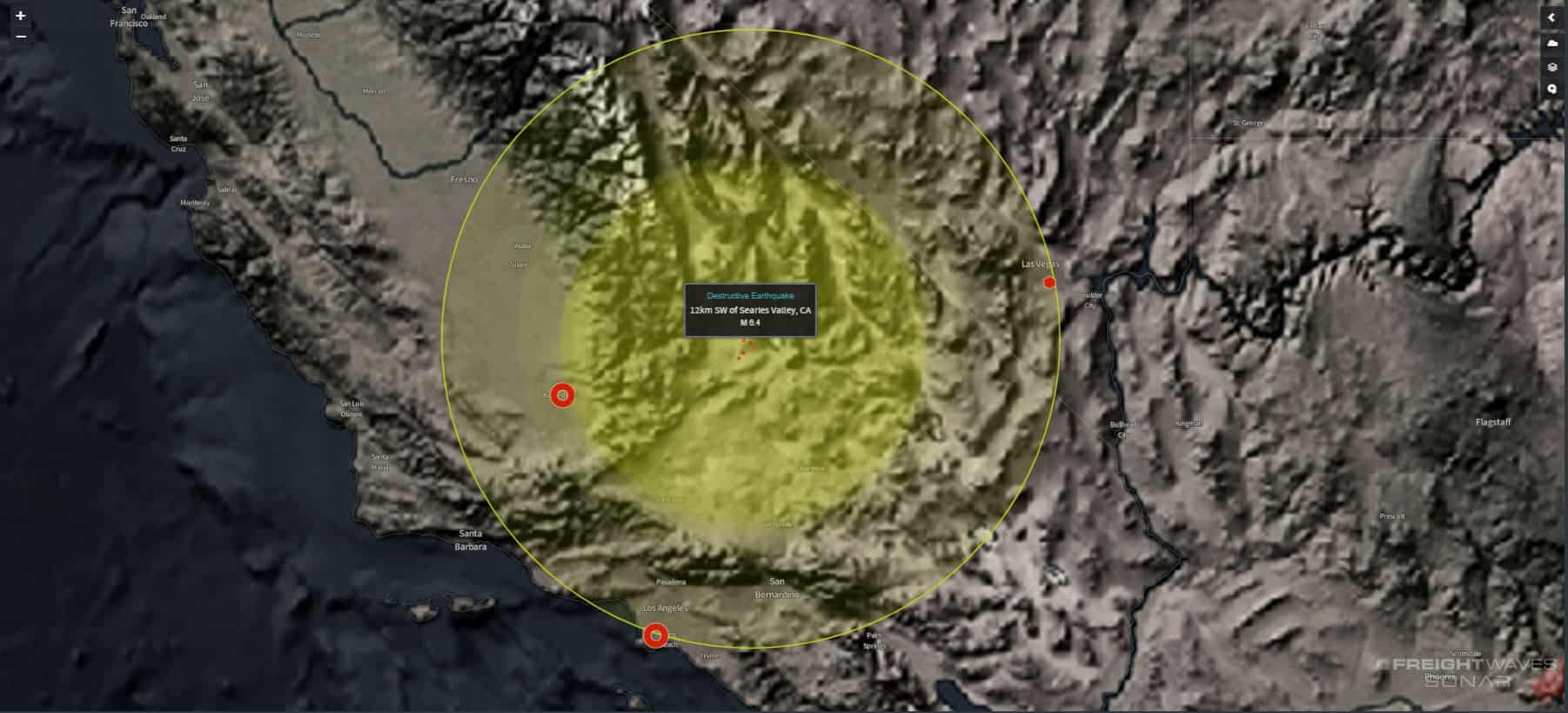

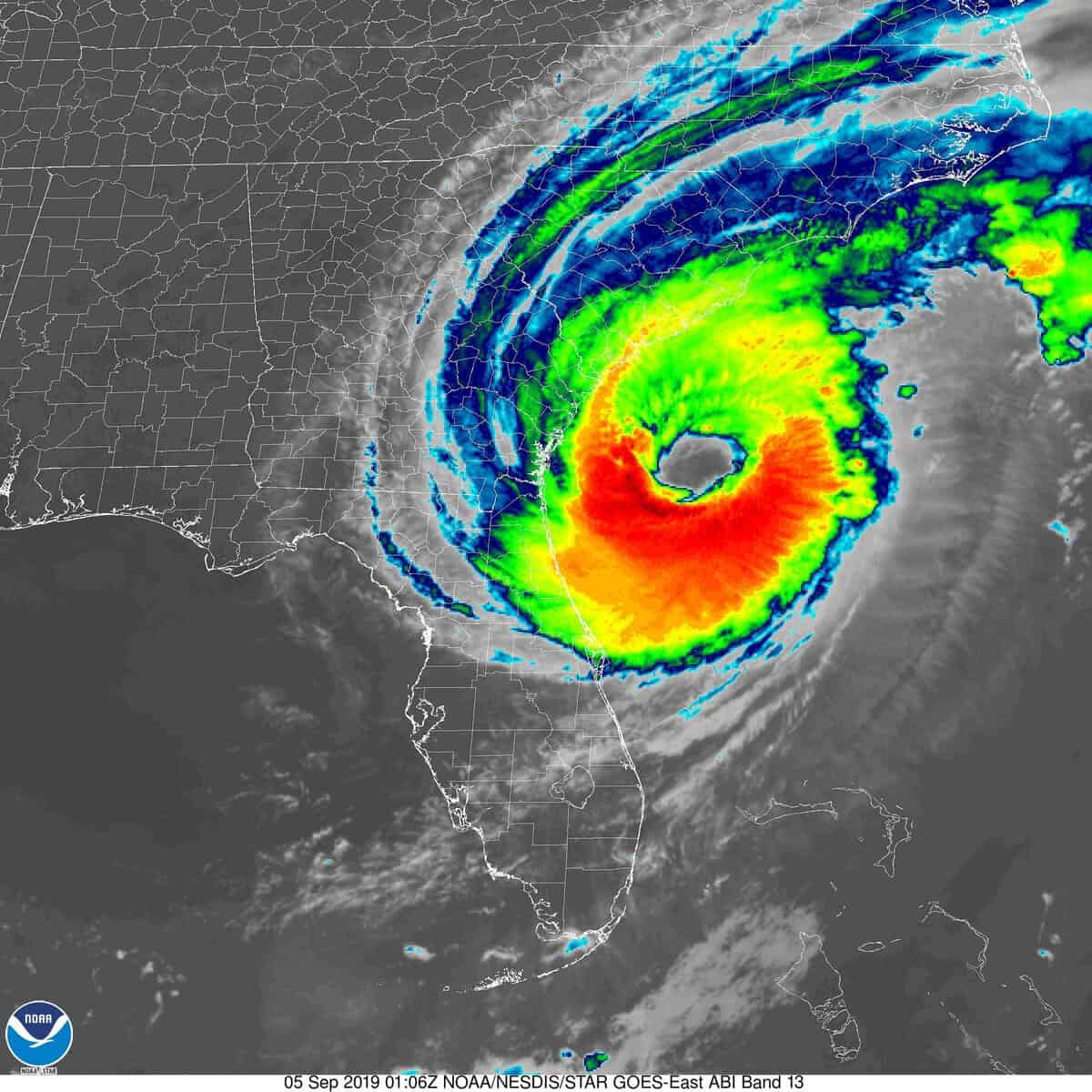

- Has witnessed several deadly meteorological disasters in the form of heatwaves, typhoons, hurricanes and floods

- Has observed politicians continue to threaten to erect trade barriers in attempts to gain an advantage over trading partners – leading to concerns that the system governed by the World Trade Organization is unsustainable

- Has woken to live and horrifying pictures of wildfires in Indonesia, the Amazon and Australia

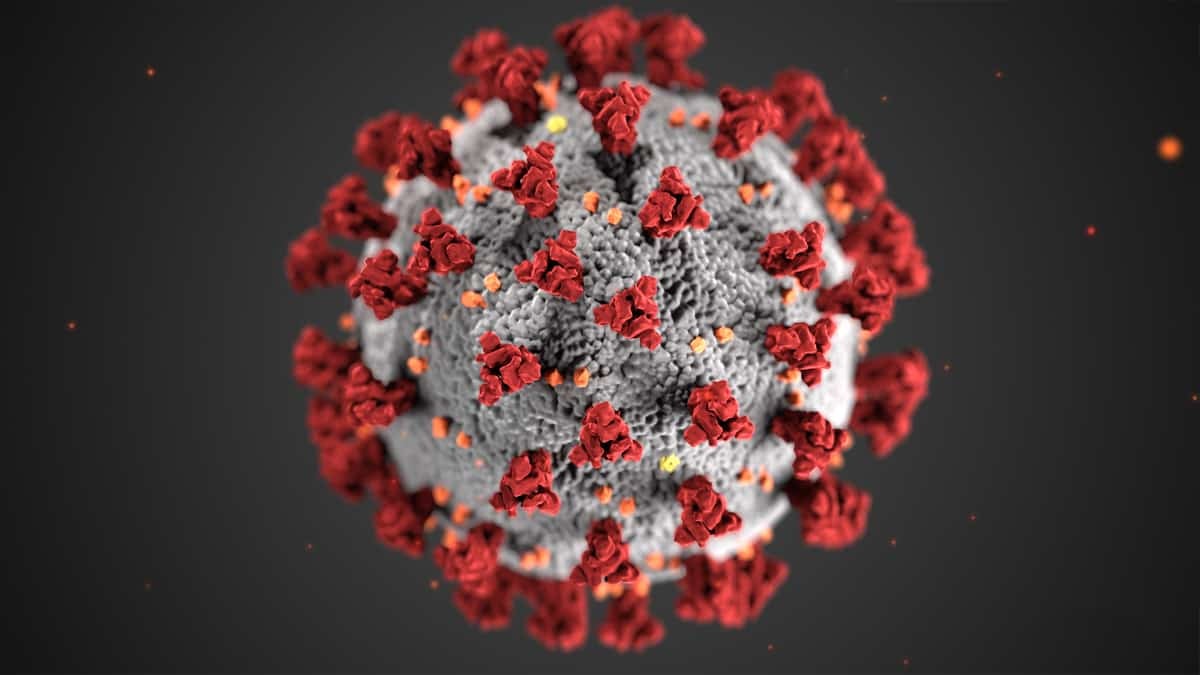

- Is presently grappling with how to contain the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)

If we assume that the future is most likely to resemble the recent past, what does this mean for global supply chains?

(Photo credit: Jim Allen/FreightWaves)

Defining the problem – endogenous and exogenous variables

In her book, Thinking in Systems: A Primer, Donella H. Meadows described a system as “A set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its function or purpose.”

In his book, Logistics & Supply Chain Management, Martin Christopher defined a supply chain as “A network of connected and interdependent organizations mutually and cooperatively working together to control, manage and improve the flow of materials and information from suppliers to end users.”

In the context of a system, such as a supply chain, there are two categories of variables that people responsible for managing the system must contend with. Endogenous variables are variables that are determined within the system. Exogenous variables are determined outside the system.

In other words, supply chain and operations managers can influence the nature and value of endogenous variables. They lack any control over the nature or value of exogenous variables. Since managers lack any control over exogenous variables, those are the variables capable of wreaking the most damage to any system. They are also the variables that are least quantifiable, and as a result they are the variables that are most likely to be ignored by managers as the system grows to maturity.

Defining the problem – network centrality

In graph theory, centrality is a measure of the importance of a given node in the graph. In other words, in the context of a supply chain, network centrality is a measure of how important a given node is to the ability of the entire network to fulfill its function or purpose. As the world becomes more volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous, highly centralized supply chains will tend to exhibit greater fragility in the face of extreme events that are beyond management’s control.

Where it is possible, companies build international operations and supply chain networks in to improve the companies’ economic productivity. If exogenous shocks continue to become more common and more extreme, corporate executives need to decide if the international strategies that they have developed to replace domestic operations and supply chains will continue to serve the purpose for which they were originally designed.

One thing that we are learning as COVID-19 has unfolded is just how central China has become to the supply chains of many large, global industries. So central, that continuing difficulties to stem the spread of COVID-19 in China could impair the efforts of health authorities in other countries as they scramble to respond to the spread of the virus because of shortages of critical medical products from suppliers in China.

For example, these statements from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show the potential severity of the problem.

- February 14, 2020: FDA’s Actions in Response to 2019 Novel Coronavirus at Home and Abroad. Among other things that statement included, “We are keenly aware that the outbreak will likely impact the medical product supply chain, including potential disruptions to supply or shortages of critical medical products in the U.S. We are not waiting for drug and device manufacturers to report shortages to us – we are proactively reaching out to manufacturers as part of our vigilant and forward-leaning approach to identifying potential disruptions or shortages. The FDA has dedicated additional resources to review and coordinate data to better identify any potential vulnerabilities to the U.S. medical product sector, specifically from this outbreak.”

- February 24, 2020: Coronavirus Update: FDA steps to ensure quality of foreign products. Among other things that statement included, “While we are not able to conduct inspections in China right now, this is not hindering our efforts to monitor medical products and food safety. We have additional tools we are utilizing to monitor the safety of products from China, and in the meantime, we continue monitoring the global drug supply chain by prioritizing risk-based inspections in other parts of the world. The FDA is not currently conducting inspections in China in response to the U.S. Department of State’s Travel Advisory to not travel to China due to the novel coronavirus outbreak. We will continue to closely monitor the situation in China so that, when the travel advisory is changed, we will be prepared to resume routine inspections as soon as feasible.”

- In addition, the bulletin CDC in Action: Preparing Communities for Potential Spread of COVID-19 illustrates how fragile the supply chain for personal protective equipment is within healthcare supply chains.

The long-term effects of exogenous shocks provide an opportunity to take steps that change the structural nature of operations and supply chain networks so that they are more resilient, and less susceptible to exogenous shocks. According to Meadows, resilience is “The ability of a system to recover from perturbation; the ability to restore or repair or bounce back after a change due to an outside force.” In a world that is increasingly more volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous, supply chain resilience becomes more important as companies jostle for market share and competitive advantage.

If you are a team working on software products to help multinational corporations develop more resilient supply chains, we’d love to tell your story in FreightWaves. I am easy to reach on LinkedIn and Twitter. Alternatively, you can reach out to any member of the editorial team at FreightWaves at [email protected].