Railroad business news seems to be all about the benefits of Precision Scheduled Railroading (PSR). That’s the name of a cost minimization business strategy introduced over a decade ago at Canadian National Railway (NYSE: CNI) – now expanding as the service model at five of the largest North American railroad companies.

Known as Class 1 railroads, these largest railways annually earn more than a regulatory agency set threshold of $500 million in revenues.

This rail freight market view column is about the service performance of the rest of the railroad companies – mostly freight carriers – that are much smaller organizations.

The thesis offered is that the smaller-sized railways offer far superior service in terms of precision-like scheduled carload pickup and carload final car placement than do the much larger railroads. How could that be?

Before defending the car service assertion, here are a few facts about short line railroads for those less familiar with North American railroading.

There are just over 600 railroad companies classified as short lines operating across the United States.

Short lines are small business companies. Some operate trains over less than one mile of track. A few short lines are much larger in terms of track miles distance.

The standard definition of a railroad short line is “Class 2 railroads earn more than about $35 million a year, but less than $500 million in revenues. Class 3 small railroads earn less than about $35 million.”

There are 50,000 track miles of short line operations according to statistics published by the American Short Line and Regional Railroad Association (ASLRRA).

While many of these small business railroads are individually owned and managed, it is estimated that about two-thirds are either owned or controlled by holding companies as a method of better managing their competitive cost structure as companies.

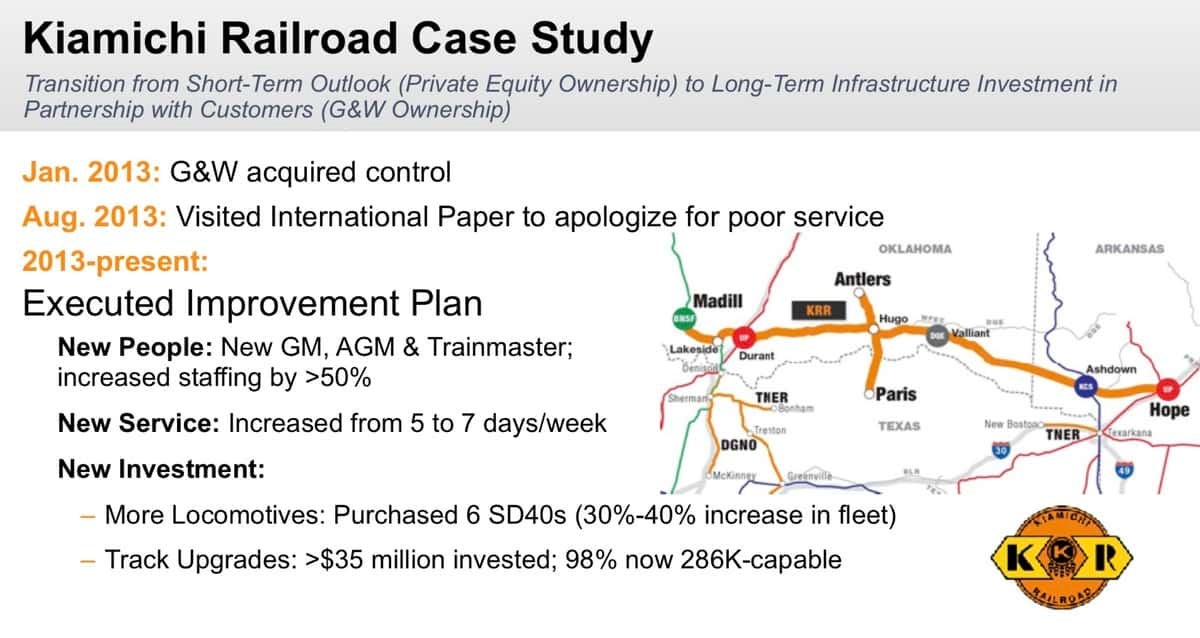

The Genesee & Wyoming (G&W) is perhaps the largest of the holding company short lines with more than 100 physically separate but united companies.

Other larger holding companies include OmniTrax and RJ Corman.

What makes railroad short lines different than their larger Class 1 counterparts?

Several service characteristics stand out when dissecting a short line market promise and its delivered operational performance. The essential difference comes down to flexibility at the local customer plant or warehouse site.

Smaller network size makes pick-up and delivery easier to manage.

Once the empty railroad car or the loaded railcar is in physical possession of the short line, actual pull or place can occur at well over 95 percent of the service expectation. In contrast, Class 1 railroad network complexity often results in an imprecise 60 to 80 percent delivery scorecard.

Here are the performance highlights of what distinguishes a short line company’s corporate health and services from a Class 1 railroad.

- Short lines typically can be profitable as long as the traffic carloads per year are about the equivalent of 100 units for each mile of track route operated by the railroad. The profit hurdle when a branch line track is owned and operated by a Class 1 railroad is significantly higher.

- Short lines are formed with a much lower manpower cost structure that includes more flexible work rules. This effectively gives the smaller railroads approximately a 25% or greater cost advantage versus a Class 1 railroad operation for what economists call the on-branch operations. That is a huge driver of short line efficiency.

- Short lines are very effective at negotiating service and shared capital project business deals with their face-to-face local customers. That was always a hurdle when the corporate headquarters of a railroad like Conrail was hundreds of miles away in Philadelphia compared to sites like Cairo, Illinois or Kewaunee, Wisconsin (site of the old Pennsylvania Railroad subsidiary Ann Arbor – then Michigan Interstate – subsidized rail/water line).

- Short lines are focused directly upon industrial development along their limited geography service tracks. They are not distracted by competitive locations that want their location to be the next job creation site.

- Short lines have a simple way to calculate customer profitability as a guide for managing their service responsiveness. Class 1 railroads have tried for decades to calculate and then share with their remote train crews information about branch line financials. The Class 1 railroads even tried to create regional cluster profit centers that would better focus attention on local branch line customers and new business development. The results were at best a mixed success. Selling off or otherwise leasing “troubled lines” to a smaller company typically became the favored big railroad divestiture business process.

- There is an ease of doing business with short lines. The difficulty of transacting business has long been an internally acknowledged Class 1 railroad issue. Local small railroads have successfully addressed this with local managers one-on-one with local customers.

The short line railroads have worked to grab growth opportunities. They developed local community and state railroad DOT programs that gave them access to development and rehabilitation capital.

Growth in business volume is a key to short line success.

G&W has documented and shared its growth success story.

- Between 1979 and 1998, the company recorded a 21% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) in revenue.

- In the 1996-2019 period, it was still an impressive 16% CAGR. (I am unaware of any similar Class 1 railroad growth pattern.)

- G&W grew its carload units by an impressive 6.5% in 2018.

- J.D. Power rates its service performance as higher than many truckers and better than most Class 1 railroads.

- Its predictable delivery and switching metrics exceed most Class 1 recorded PSR deliverable rates.

- Many of its short lines achieve PSR goals – like 60% operating revenues – but without the reported customer service disruptions.

Conclusions

Short lines have clearly shown how to not only preserve local railroad service, but have also prospered financially.

The significant decrease in on-line short line branch operating costs can’t be overlooked. A 25% or higher cost reduction can be a game-changer in local rail service economics.

Yet there is a warning. Not every short line railroad survives. One estimate is that about one-third of the small railroad business units are financially marginal.

The next opportunity for short lines might be to become large low-traffic density managers and traffic sales forces for carriers like CSX or Norfolk Southern that may seek to divest large groups of marginal branch lines to the short lines in the near-term. The historical pattern is that branch line abandonments or spin-offs come in cycles. America under the PSR business model can clearly expect the next wave of marginal Class 1 branch line spin-offs.

Acknowledgements

While the business thoughts expressed herein are those of the author, it is important to reference the contribution others have made to the facts and business theories of this short column.

Want to know more? Seek out the following:

- Chuck Baker and the ASLRRA technical staff in Washington, D.C.

- Michael Miller, President North America G&W – NEARS Oct 2019

- Michael Sussman, Strategic Rail Finance, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- Michael J Connor, former Conrail LDL Director and expert