More numbers have emerged on exactly how quickly Amazon’s disruption of the transportation and logistics is proceeding.

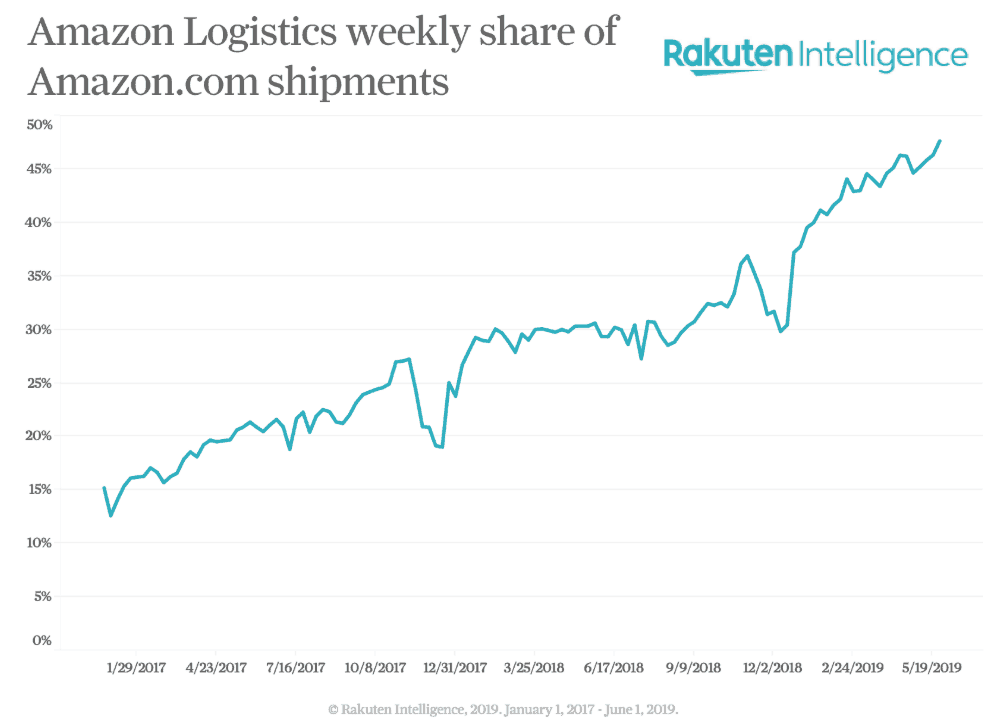

On Thursday, Rakuten Intelligence reported that in the months of March and April Amazon carried as much as 45 percent of its own shipments. Rakuten Intelligence is the big data and business intelligence subsidiary of Rakuten, the electronic payments and e-commerce giant of Japan.

In January 2017, Amazon was handling just 15 percent of its own parcel shipments.

“During the 2016 holiday season, Amazon handled 8 percent of its final-mile shipments – that number increased to 20 percent in 2017 and to 30 percent in 2018,” Rakuten reported. “This year, in March and April – an off-peak time of the year – Amazon is carrying as much as 45 percent of its own shipments. In just a few years, the largest online retailer has methodically shifted its share of volume from carriers like USPS to its in-house delivery service.”

Amazon now employs more people than FedEx, UPS, or the United States Postal Service, according to Rakuten. Amazon’s headcount now tops 648,000, growing its work force by 5.5 times since 2013.

Armstrong & Associates pointed out in its yearly 3PL report that if Amazon was considered a third-party logistics provider — and we think it should be — it would have the second-largest warehousing operation in the world after DHL Supply Chain and Global Forwarding. Amazon manages about 233 million square feet of warehouse space, more than XPO (190 million) and less than DHL (248 million).

Amazon freight flows through that logistics infrastructure network — which now totals more than 390 structures, according to Rakuten — on 50 planes, 300 trucking power units, and 20,000 Sprinter vans. Thousands of Amazon trailers, now a common sight on U.S. interstate highways, are being hauled by Amazon’s contracted carriers, many of them sourced through Amazon’s digital freight brokerage platform.

Several American transportation companies have been caught off guard by the explosive growth of Amazon’s logistics capabilities. XPO Logistics guided revenue down when Amazon pulled hundreds of millions of dollars worth of postal injection business from the less-than-truckload carrier. FedEx, which had considered Amazon a valuable customer just a year ago, publicly broke up with the e-commerce retailer earlier this month, saying that its Express division — its largest business unit consisting of air cargo and next-day delivery — would no longer do business with Amazon.

FreightWaves’ proprietary research group, Freight Intel, has published an in-depth study of Amazon’s impact on the transportation and logistics sector, research that is now live on the FreightWaves SONAR platform. One of the findings from that study suggested that trucking carriers perceived Amazon’s entry into freight brokerage more negatively than they perhaps should, while shippers were not taking the threat seriously. The theory was that Amazon would have to pay carriers something close to market rates to ensure that capacity showed up, while any shipper using Amazon’s logistics services would be foolish to give up control of its supply chain data and freight to one of its most ruthless competitors.

However, recent reporting by Business Insider has confirmed that indeed, Amazon is paying trucking carriers below-market rates and that drivers who are happy to order personal goods from the e-commerce company are unwilling to haul freight for it.

Even as Amazon has gradually raised rates on its Prime subscriptions by 50%, from about $80 to $120, its operations have gotten sloppiers as it has scaled. According to Rakuten, in 2017, about 5% of items arrived late, while in 2019, that number had tripled to 15%.

Amazon Prime’s performance has been more or less efficient over the years as Amazon uses it as a high-pressure laboratory to understand and work through the bottlenecks in its network.

According to one ex-Amazon executive who corresponded with FreightWaves, Amazon’s in-sourcing of its logistics capabilities was initially driven by fear. Amazon did not want transportation capacity to constrain its growth, and feared its lack of control over a fragmented, volatile industry.

Amazon entered transportation to survive, is now disrupting the industry by disintermediating its previous transportation providers, and has already begun monetizing the network built up, leveraging a stealth-mode digital brokerage platform to generate revenue by filling backhauls and repositioning its trailers.

“That’s the true Amazon flywheel: disintermediate to survive; monetize to fund innovation; innovate to grow; disintermediate to survive,” the executive wrote to FreightWaves.