Electrifying just the long-haul portion of the U.S. trucking fleet would gobble 10% of the nation’s electric power generation, according to a study from the American Transportation Research Institute.

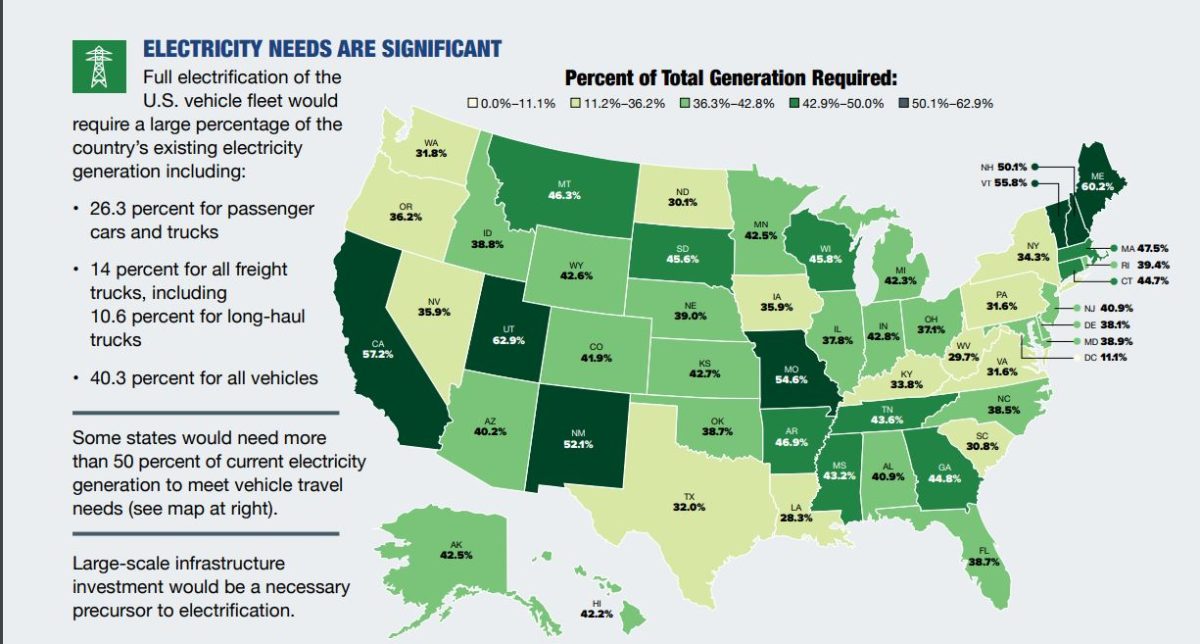

And electrifying all cars and trucks would need 40% of the grid output, ATRI said in a report released Tuesday.

Supply and demand, electric vehicle production and truck charging

ATRI’s Research Advisory Committee made a top priority of understanding infrastructure requirements for an electrified U.S. vehicle fleet. It focused on three critical challenges: U.S. electricity supply and demand, electric vehicle production and truck charging requirements.

Key findings:

- Domestic long-haul trucking would use more than 10% of the electricity generated in the country today.

- An all-electric U.S. vehicle fleet would use more than 40% of grid capacity.

- Some states would need to generate as much as 60% more electricity than presently produced.

The ATRI study is the newest but not the only analysis of grid demand. An Electric Highways Study by National Grid Group had similar findings. Power demands in just New York and Massachusetts would need to grow until many are consuming as much electricity as a small town or a large factory.

Draining global reserves

ATRI’s analysis also found that tens of millions of tons of cobalt, graphite, lithium and nickel would be needed to replace the existing U.S. vehicle fleet with battery electric vehicles. And it could take 6.3 to 34.9 years at current production levels to meet the demand. It is the equivalent of 8.4% to 64.4% of global reserves — for just the U.S. vehicle fleet.

An existing challenge — truck parking — also is in the mix. Charging the nation’s long-haul truck fleet will require more chargers than there are truck parking spaces in the U.S., ATRI found. Hardware and installation costs $112,000 per unit, or more than $35 billion for a nationwide system.

These are reasons why a full transition to electric trucking is unlikely, at least for a long time.

‘Daunting task‘

“ATRI’s research demonstrates that vehicle electrification in the U.S. will be a daunting task that goes well beyond the trucking industry,” said Srikanth Padmanabhan, president of engine business at Cummins Inc. “Utilities, truck parking facilities and the vehicle production supply chain are critical to addressing the challenges identified in this research.”

Cummins is pushing a variety of drop-in fuels — hydrogen, natural gas, propane and even gasoline — to help the transition to zero-emissions trucking. It will offer a 15-liter natural gas engine with performance close to diesel power in 2024. Then, in 2027, it plans a version of the engine that can burn hydrogen without a fuel cell.

“Carbon-emissions reduction is clearly a top priority of the U.S. trucking industry, and feasible alternatives to internal combustion engines must be identified,” Padmanabhan said. “Thus, the market will require a variety of decarbonization solutions and other powertrain technologies alongside battery electric.”

The ATRI report notes that while certain applications make sense for battery-electric trucks, a new charging infrastructure is critical to increasing their adoption by the trucking industry. And the raw materials needed for batteries will likely need to be re-sourced with an emphasis on domestic mining and production.

Related articles:

Cummins previews coming attractions as emissions regulations converge

Pilot and Volvo Group add to public electric charging projects

A startup’s big better on a Southwest electric truck corridor