FreightWaves features Market Voices – a forum for market experts with unique knowledge of numerous transportation/logistics/supply chain sectors, as well as other critical expertise.

Everything we plow, harvest or mine started as rock and evolved in time. Given enough time, solid rock exposed at the earth’s surface is broken down into rock and mineral fragments by weathering into what geologists call “surficial materials.” Laymen call it dirt, soil, rock or metallic and non-metallic minerals.

In it naturally decomposed state, these “commodities” have a low in-place utility. Move it somewhere else and its market value increases.

Multiple kinds of stone deformation are important to civilization. One is high-quality deformation such as high-grade sand. Let’s first review what is called fracking sand, or frac sand.

The second market is stone and gravel.

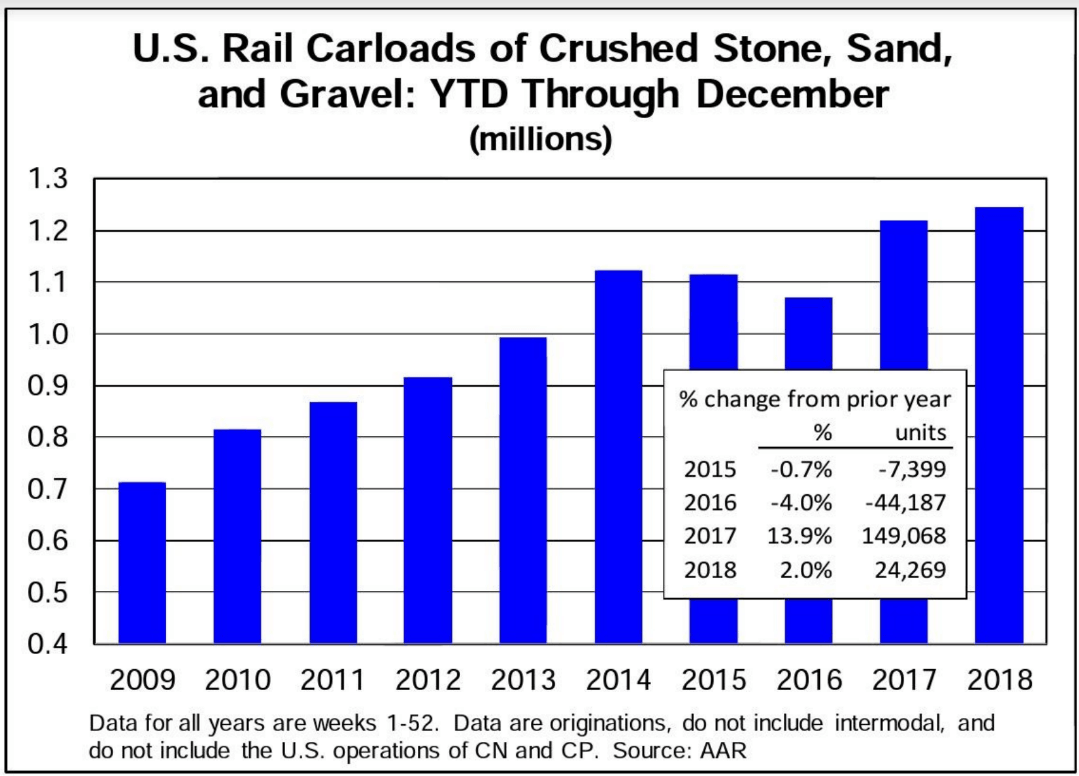

To move both sand and stone and gravel to market rail transportation is heavily relied upon. In 2018, more than 1.2 million carloads of aggregate and sand were moved by U. S. railroads.

Frac sand rail market view

Industrial sand is a high purity silica historically sold for glassmaking, chemical production, paints, ceramics and refractories. Its most recent use is in the oil and gas recovery industry.

Frac sands are typically more than 99 percent quartz or silica – with each particle well-rounded with few impurities.

Frac sand is a type of proppant.

Hydraulic fracturing is a technique in which fluids and proppants are forced under pressure down a drilled hole to crack open source rock. This helps release trapped oil and gas. Proppant props open the cracks, allowing a freer release of oil and gas during pumping.

Fracking of oil and gas has been growing as a preferred method since about 2008 in North Dakota (the Bakken fields) and now in Texas (the Permian field) shale drilling.

The highest quality frac sands are found in Wisconsin and Minnesota. Given the long distances between these sand deposits and the shale fields, rail freight is unquestionably the cheapest transport mode. Rail distances range from about 400 miles to as much as over 1,800 miles.

Railroad frac sand equipment is usually a covered hopper railcar type. This protects the moisture content and prevents cargo loss from wind as the railcar moves along the rails.

Covered hopper railcars are typically going to “weigh out” in tonnage before they “cube out” (or fill up). Most covered hoppers are in the 2,400- to 3,200-cubic foot size. There are more than 121,000 covered hopper freight cars in service as of early 2019.

Figure 2 identifies the dimensional drawing of a covered 3,250 cubic foot covered hopper car. Dimensions are 42 feet length over couplers.

Sand might be priced at the mine at some locations at $40 to $50 per ton. Rail haul can then add between $30 and $70 a ton to the delivered price.

Some frac sand freight trains are long. During 2015 BNSF operated a 150-car unit train – with 16,500 tons of frac sand. It moved sand from Ottawa, Illiinois to Clovis, New Mexico.

Frac sand market shifts

Commodity markets are subject to a variety of economic forces. White Northern frac sands from Wisconsin are superior in quality at the “proppant” function than are lower quality but closer regional sourced sands. Recently, oil and gas field buyers have shifted (at least to some extent) to the lower quality and cheaper to transport near-by regional sand sources. That happens when the price of a barrel of oil drops. The oil drilling sector then often shifts to preserve its profit margin.

Experience shows that all commodity markets are, in the long run, subject to random up and down cycles.

With such shifts, railroad company revenues and railway freight car builders’ business will be hurt.

A shift towards more local Texas frac sands theoretically computes to a possible 5 to 10 percent savings in transportation costs. That might not sound like much, but for a typical Texas well, it could represent a saving of between $400,000 to $500,000 per well.

Predicting the railroad sector market downside or upside outcome is more of an economic “forecasting art” than it is a science.

The capital risk is long-term. New freight cars can easily operate for 35 or more years. The risk question comes down to rail freight’s sand movement long-term role if too many cars are bought to support the rail business.

A few 2019 frac sand conclusions

Expect the railway frac sand market to be both a selective opportunity and a “hedge” risk if you’re in the rail operating or railway car building business sector.

Frac sand tonnage moved by railcar and carloads continue to grow into 2019.

Yet, “past performance and growth patterns are not a future pattern guarantee.” The exuberance of crude oil rail tank car purchasing between 2008 and 2015 is your business case reminder. There could always be a cyclical bubble.

The biggest cyclical risks are a combination of lower per barrel oil market prices, a surplus of light crude, higher consumer efficiency use patterns, growth in substitute fuels, and a lower than expected producer financial yield per frac sand well.

A possible but not yet proven rail offset would be if the railroads increased their operational performance to gain as much as two to four additional car loadings per year. That might help them retain or even gain market share versus the regional trucking threat.

Buyers continue to increase the substitution of lower-quality sand mined near the wells to avoid the cost of long-haul rail moves. Because shipping “can account for up to 70 percent of the delivered cost of Wisconsin sand,” this transition will hurt railway revenues.

On the plus side, older frac wells typically used about three railroad carloads of frac sand. Newer longer ‘horizontal reach’ wells use as many as 30 or more carloads of this sand.

Stone and gravel rail transport market view

Crushed stone and gravel are called construction aggregate. From the BC era to today, construction aggregates are a foundation for roadways, bridges, and various domestic and commercial building structures. The materials are quarried, sorted, crushed and then moved to the construction sites. The closer to the quarry, the better for cost control.

Stone is used as a mixture in both concrete and asphalt paving. It’s also used as a drainage and a track support foundation (called ballast) under and between railroad ties (sleepers).

Granite and trap rock are the second and third most commonly used types of rocks for producing crushed stone.

During 2017, U.S. Class I railroads moved 1.5 million carloads of sand, stone and gravel. That covers both high-quality frac sands and construction aggregates.

Two types of railcars are used for crushed stone and aggregates – open top hoppers and flat-bottomed gondolass.

Modern aggregate railway gondolas are typically 42-feet long and have a capacity of up to 115 tons. The most recent car design supports the movement of both phosphate and aggregate.

The newest cars are rated at 286,000 gross pounds when loaded (heavy axle North American standard).

Besides aggregate construction, railroads move phosphate. Most phosphate deposits are in Florida, Idaho, Montana and Utah. More than 80 percent of U.S. phosphate is used for agricultural fertilizer.

A few conclusions as of 2019 about the aggregate rail market

Basic construction use rock and fertilizer may not be a glamorous business, image-wise. But it is profitable, and it appears to be a steady growth railway market.

Between 1950 and 2000, U.S. statistics show that crushed stone, gravel and sand increased from an overall 62 percent of all non-fuel mineral mining to about 75 percent. As long as mankind builds infrastructure and buildings, there will be an aggregate market. It is less cyclical than the frac sand market.

——–

Metrics used herein came from a variety of sources. Credit is given to the following for some of their published research:

- David Christianson, Minnesota Department of Transportation

- Taylor Robinson, PLG Consulting

- Will Geiger, Railroad Financial Corporation

- Dan Keen, Association of American Railroads