This quarter can’t end soon enough for dry bulk, the largest freight market in the world by cargo volume.

Rates for Capesizes — bulkers of around 180,000 deadweight tons (DWT) that carry iron ore and coal — have wallowed disastrously in the $2,500-$5,000-per-day range since January. This will be the second-worst quarter ever for Capes after the first quarter of 2016.

Now is typically the time of year when rates turn and begin their seasonal climb, but this is not a typical year. April forward freight agreement (FFA) Capesize contracts closed at $4,381 per day on Thursday. The second-quarter FFA closed at $6,083 per day; in early January, the second-quarter contract traded at $11,500 per day.

“The futures are telling you that it will be the worst April ever and the worst second-quarter ever,” said John Kartsonas, founder of Breakwave Advisors, the company that developed the Breakwave Dry Bulk Shipping ETF (NYSE: BDRY).

“The market is pricing in a very, very distressed market for Capesizes,” he said.

Why are rates so low?

The two most important Capesize trades are Brazil-China and Australia-China. Even though rates from Australia have been lower than from Brazil, Kartsonas maintained that Brazil is the root of the problem.

Australia had cyclone disruptions in February, but Kartsonas believes the main issue has been overcapacity in the Pacific Basin due to weak rates in Brazil. After Capesizes unload cargo in China, Brazilian rates have to be high enough to justify the time and fuel expense of ballasting empty all the way to the Atlantic Basin.

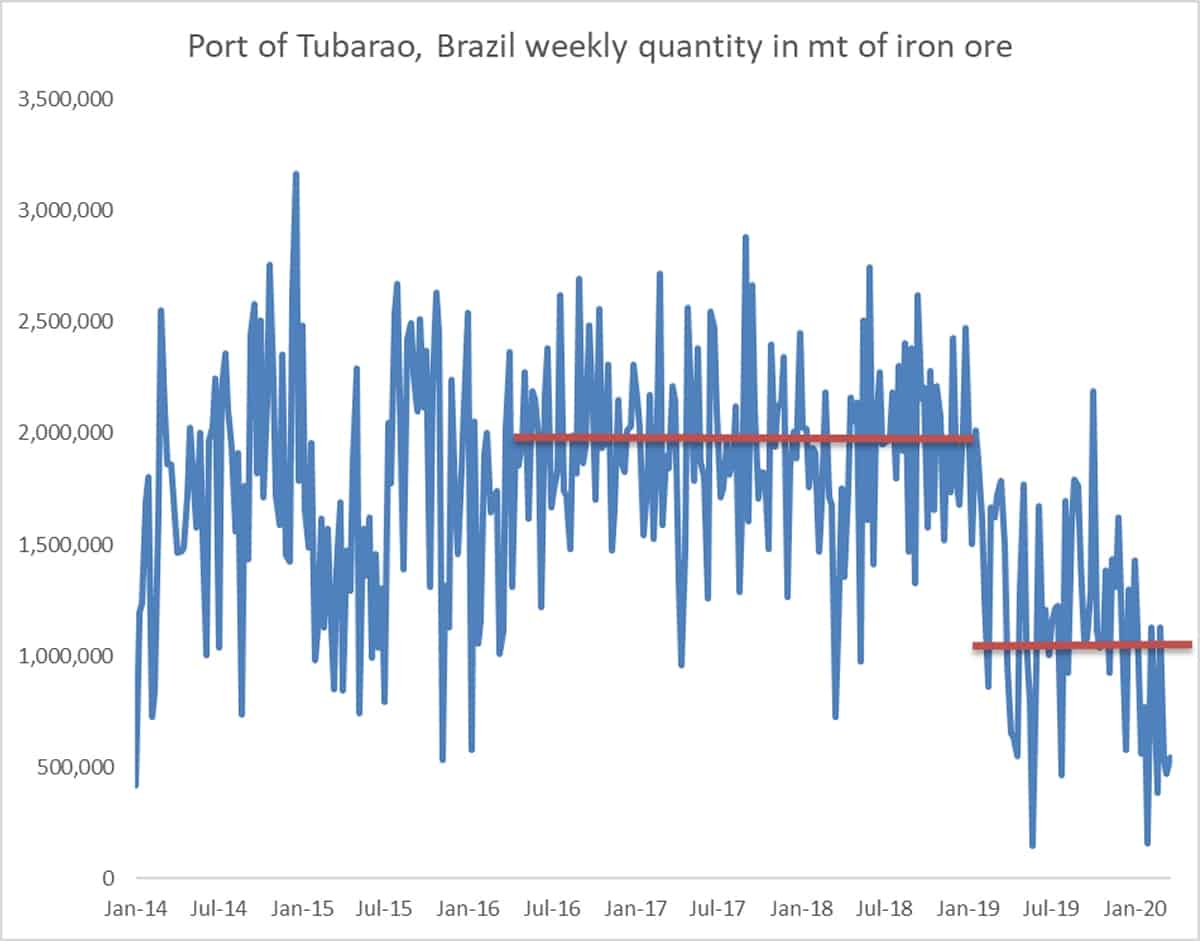

Rates out of Brazil have been weakened by a shortfall of iron-ore exports by miner Vale (NYSE: VALE). There are two reasons: unusually heavy rains and ongoing safety precautions stemming from 2019’s tailing dam accident. “This is not about coronavirus. This is 90% about Brazil,” asserted Kartsonas, who highlighted that volumes out of the port of Tubarao (one of Brazil’s two main iron-ore ports, along with Ponta da Madeira) have been cut in half.

“March is going to be a record low for exports out of Brazil, and without Brazil, the Cape market cannot recover,” he said.

Despite the coronavirus shutdown in China earlier in the quarter, Kartsonas does not believe the problem is lack of demand from that country. “Chinese steel production is back to normal levels as of this week. Iron ore is at $90 [per ton] — it’s the best-performing commodity in the world right now. If there was a lack of demand from China it would be at $60. Iron-ore prices are telling you that the market is tight.”

Risks to the upside

“If you look at the basic fundamentals of dry bulk — the end of the rains in Brazil, the talk of stimulus in China — I think you’re probably looking at a better risk-reward [balance] than the futures are telling you,” Kartsonas said. “If you get better volumes out of Brazil, I wouldn’t be surprised to see the BDI [Baltic Dry Index] double.”

Then why are April and second-quarter Capesize FFA contracts so low? “I think most of the people who trade [FFAs] are in the Western world, in London and Geneva and places like that,” Kartsonas answered. “Everybody’s affected by what’s happening [with coronavirus], sitting at home and trying to make sense of the world. They probably don’t have the most optimistic macro perspective right now. Also, it may be derisking: People may be being told, ‘Listen, forget about trading freight for now.’”

One way investors are betting on a positive turnaround is through the BDRY exchange-traded fund (ETF), which was launched in March 2018 and is designed to mimic the moves of the BDI.

BDRY invests in a mix of FFAs that track rates in the Capesize, Panamax (65,000-90,000 DWT) and Supramax (45,000-60,000 DWT) categories.

The value of these FFAs, recalculated daily, is the fund’s net asset value (NAV). The value at which BDRY trades on the NYSE cannot diverge significantly from NAV for an extended period.

Kartsonas explained, “Dry bulk stocks follow sentiment, investment flows, what’s in favor and what’s not in favor, things that have nothing to do with [shipping] fundamentals. BDRY just follows the rates, no matter what.”

Last year, he recalled, both BDRY and dry bulk stocks hit lows earlier in the year, then rates recovered through August and September. During that period “dry bulk stocks as a group were up 20-25% but BDRY rose by more than 120%.”

Over the past few months, trading volumes in BDRY have surged. “Volumes are the highest ever and assets have increased significantly. We have been adding assets every week for the last two months,” Kartsonas said.

In an open-ended ETF like BDRY, as investors buy stock, the money flows into the fund and the fund buys the underlying securities. Increasing assets mean that investors are “long”, i.e., bullish on future pricing. If investors are bearish, the ETF would see redemptions and a decrease in assets.

“You’re looking at the lowest prices for freight in many years. Can they go lower? Of course. But the higher risk is that rates actually snap back on seasonality, China and better weather in Brazil. I think the broader trade that people are entering into here is: long China, short the Western world.”

Risks to the downside

There are clear risks to the downside, as well. First, coronavirus could cause a global recession or depression, curbing industrial production, including in China, thereby reducing steel production and thus demand for Capesize cargoes.

Second, coronavirus could reflare in China itself, shutting down the steel mills, terminals and transport systems yet again.

Third, coronavirus could shut down the export centers for Capesize cargoes. This is already beginning to happen. Colombia has instituted a halt to mining through April 19. South Africa has closed its mines through April 16.

“Closures in Colombia and South Africa will create a short-term disruption but it should not affect expectations beyond April,” Kartsonas said. “However, if anything like that were to happen in Brazil or Australia, it would be a major disruption for Capesizes.”

Concerns are rising in Brazil, where coronavirus cases are higher than anywhere else in Latin America, infections are climbing rapidly, the hemispheric winter is coming, and President Jair Bolsonaro has dismissed the outbreak as a “media trick.”

One FFA market participant told FreightWaves, “In case of a supply shock where operational suspensions occur across Brazil and Australia, freight rates should tumble even further, to levels not seen for quite some time.”

But Kartsonas does not believe investors are pricing in a Brazil shutdown. “If there was any concern about Brazil shutting down, iron ore would be much higher [than $90 per ton],” he said. “Iron ore is the second-most traded commodity in the world after crude oil. You wouldn’t bet on an iron-ore shutdown by trading second-quarter freight futures. You’d trade iron ore, which is much more liquid, and the iron-ore futures are telling you that investors are not concerned about this risk.”

Index overviews

Capesize rates are tracked by the Baltic Exchange’s 5TC Index and since last year, a competing index with a different methodology produced by S&P Global Platts: the CapeT4 Index.

Platts produces dual indices, one for Capesizes using exhaust-gas scrubbers burning traditional 3.5% sulfur heavy fuel oil (HFO) and one for nonscrubber Capes burning 0.5% sulfur fuel known as very low sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO). The Baltic 5TC Index is priced on the basis of VLSFO fuel use.

FreightWaves has developed a series of charts covering first-quarter Cape performance based on data from Platts and the Baltic Exchange.

As of Thursday’s close, Platts’ scrubber index was assessing a time-charter equivalent (TCE) rate of $6,725 per day and the nonscrubber index was at $4,541. The Baltic 5TC was at $3,818 per day.

Looking at the dual Platts CapeT4 indices year to date (YTD), the base rate, i.e., the nonscrubber index, has stayed relatively flat. It’s now down 8% YTD. Scrubber rates, in contrast, have plummeted by 59% YTD, almost entirely due to the collapse in the spread between the price of HFO and VLSFO.

A TCE rate is calculated for spot contracts by taking the dollars-per-ton spot rate and converting it into a dollars-per-day rate. The cost of fuel is netted out (subtracted). In early January, when VLSFO was much more expensive than HFO, scrubber ships saved much more, meaning their TCE rate was much higher for the same dollars-per-ton spot rate. Scrubber savings are now down 81% YTD, erasing much of the value of installing scrubbers.

Looking at the individual trade lanes that make up the CapeT4, Australia-China has seen a 32% decline YTD in the nonscrubber rate and a 68% drop in the scrubber rate.

On the Brazil-China lane, despite all the concern over Vale’s iron-ore exports, nonscrubber Capesize rates are actually up 22% YTD, according to Platts. Scrubber rates have gone in the opposite direction, down 53%, as a result of a 79% drop in scrubber savings.

In the third most important Capesize trade, from South Africa to China, nonscrubber rates are effectively flat YTD (up 2%), while scrubber rates are down 54% due to the declining HFO-VLSFO spread.

Finally, in the smallest component of the CapeT4 Index, the Colombia-Netherlands coal run, nonscrubber rates are down sharply, by 49%, with scrubber rates down 61%. Click for more FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller