Along with the pain of higher prices in general at the pump, truck drivers are dealing with the fact that diesel has risen beyond increases in crude and gasoline.

The numbers are stark on how much diesel has risen relative to other benchmark oil prices in recent weeks. According to the Department of Energy’s Energy Information Administration (EIA), retail gasoline is up 26% from the start of the year — but diesel is up 42.8%.

While it’s easy to blame the Russia-Ukraine war, given the enormous role of Russia as a supplier of diesel, the reality is that the price of diesel compared to crude and gasoline began to increase well before Russia’s invasion.

The price that truckers pay at the pump always is determined primarily by the price of crude. But if the relationship between crude and diesel goes through structural changes that tack on another 10 to 15 cents a gallon to the spread, those gains are going to impact the retail price of diesel even if crude sits perfectly still.

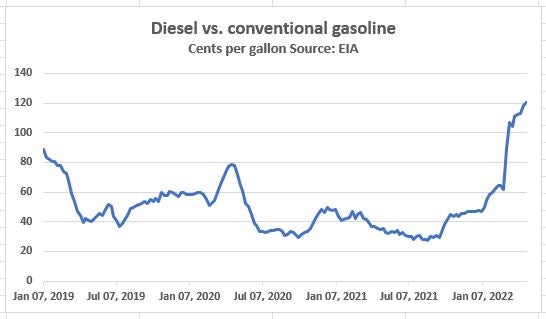

Just how much has that spread widened? The accompanying chart shows the spread between retail gasoline and retail diesel, according to the average price published each Monday by the EIA.

For the diesel-consuming industry, this price isn’t some abstract figure popped out by the government; it’s the basis for most fuel surcharges. A year ago, that spread was just under 40 cents a gallon. Based on the most recent prices published Monday, the spread is now about $1.20 a gallon.

But the retail price is at the end of a long supply chain that includes crude production, selection of types of crudes for a refinery to process, and the split in refinery output among gasoline, diesel, jet fuel and other products. That growth in the gasoline-to-diesel retail spread ultimately is the final step after changes in the spot products market.

On Monday, the simple spread on the CME commodity exchange between the front month Brent crude price and that of ultra low sulfur diesel was $1.65 a gallon. Part of that number reflects this week’s squeeze in the diesel market. With the May contract on CME heading toward expiration Friday, traders with short positions needing to close out their trade before the end of the week found barrels scarce. So it is a one-off that will come to a conclusion before Friday.

Even if numbers from this week are loosely ignored as having been caused by those unique circumstances, it’s hard to overstate just how out of whack the spreads between diesel and Brent crude have become.

The spread crossed the $1-a-gallon mark on March 18. At the start of 2022, it was about 47 cents. For all of 2021, the spread averaged less than 40 cents. (Brent is the preferred benchmark for comparison because it is the global crude benchmark and diesel is traded globally as well.)

These movements obviously are not all driven solely by the Russia-Ukraine war. So what is happening?

Philip Verleger is an energy economist who has diesel in his sights. For example, in the spike to what remains the all-time-high crude price — $147 for West Texas Intermediate at the beginning of July 2008 — Verleger was unique among analysts in citing changes in diesel specifications as the tail wagging the dog. Diesel was dragging up crude, Verleger argued, not the other way around.

Verleger: Structural changes in the diesel market are boosting prices

In a recent report, Verleger makes a similar argument. He sees the biggest difference as the structural changes in the market, many of them related to government mandates, having permanently altered the diesel market into a situation where traditional spreads between crude and diesel, and diesel and gasoline, have disappeared and won’t be returning. (Addendum: Nothing in the oil market is truly permanent, so it’s a relative term.)

In his report, Verleger lays out five basic facts about diesel’s chemistry, which is key to understanding why its supply has tightened so much and why its price has climbed well beyond increases in crude and gasoline.

Two factors Verleger cites are well known: Refining oil produces a level of diesel that is a percentage of output but which structurally can’t be easily increased; and that each crude has its unique chemistry that produces varying yields of diesel and other products.

But Verleger also cites lesser-known factors.

One, the low-sulfur crudes that are good feedstocks to make desulfurized diesel are in declining supply. Two (and this ties back to the low-sulfur supply), sulfur must be removed from diesel due to government mandates. And three, “such desulfurization capacity is limited and expensive to construct.”

“At this point in 2022, these considerations have combined to limit the low-sulfur diesel supply,” Verleger writes, citing some of the various spreads such as gasoline vs. diesel.

Verleger looks to the forward diesel curve as an indicator of just how unusual the diesel market has become — as he says, it is a chart “that seems to come from an entirely different sample, or universe.”

In a perfectly balanced market, the price of any commodity as it goes out the calendar rises, to reflect the time value of money and the cost of storage. So July widgets will be somewhat more expensive than June widgets, August widgets will be more expensive than July widgets and so on.

When markets get tight, the most valuable widget is the one that can be delivered right now. The highest price is in the first month (or other time period), the next most expensive is the next time period out and so on. It’s known as backwardation. It is a sign of a tight market, and in diesel now, it’s a doozy.

Diesel prices down the calendar show the extent of the tight market

Verleger cites statistics of the spread between the first month and the third month for the ultra low sulfur diesel market on the CME commodity exchange. But the 12-month spread also has been sitting at unprecedented numbers.

Verleger refers to it as the “hoarding premium.” His report cited the three-month numbers, but the same phenomenon is occurring in the 12-month numbers. The 12-month backwardation for the year between February 2021 and February 2022 averaged a little more than 7 cents a barrel. Earlier this week, it was more than $1.18 a barrel, for a 12-month “hoarding premium” of around $50 per barrel.

This is unprecedented and is driven in part by the ongoing end-of-month squeeze. But even if that passes, Verleger’s report sees other factors at work in the current market, beyond the sulfur-related structural issues he cited.

In a separate five-point list, Verleger mentioned ongoing issues with the diesel market.

— The increased demand for low sulfur-diesel.

— A decline in Nigerian oil production, which is reducing supply of a key low-sulfur crude.

— “Limited desulfurization capacity.”

— The use of gasoil, a diesel-like product in Europe, to generate electricity because natural gas is so expensive.

— Sanctions against Russia, by governments or private companies, choking off a significant supply of diesel.

In discussing higher demand, Verleger cites an issue that was hot three years ago but disappeared from the front burner: the marine fuel regulation known as IMO2020. On Jan. 1 of 2020, it went into effect worldwide, mandating fuel for ships with much tighter sulfur specifications. (IMO stands for the International Maritime Organization, the global organization that established the rules.)

It was expected that molecules, which would otherwise be made into diesel, would be diverted to produce a fuel that complied with IMO2020. The fear and consensus in the market was that such a diversion would boost diesel prices.

Then the pandemic hit, demand cratered and fears of a shortage of diesel disappeared. But although it is just a brief mention in his report, Verleger sees it as a factor in today’s market. “Trucking and rail activity has risen,” he writes. “The transition to low-sulfur marine diesel has also raised use.”

Verleger does not see the squeeze ending anytime soon.

“Given these circumstances, distillate may be in short supply for months or years absent changes in regulatory policies, an economic slowdown that reduces demand, or technical advances,” he writes. “In the short term, distillate prices will likely keep rising compared to other petroleum products.”

The weekly Verleger report has a projected price for crude based on several factors, including product prices and intermonth relationships. He conceded that recently, the model has been wrong, and the crazy distillate market is the reason.

But it’s not just a one-time mistake. Rather, he says, it could be a harbinger of things to come. He notes that diesel use is demand that is not elastic, because it tends to get consumed by intermediaries, such as truck drivers. As the price increases, demand doesn’t decline the way gasoline use does.

“Consequently, distillates could pull prices to unimaginably high levels absent a significant economic slowdown,” Verleger said in a highly bullish conclusion.

More articles by John Kingston

Diesel sees highest price, biggest increase in history of DOE/EIA benchmark

Granholm calls for more oil production while diesel plunges for the day

Want renewable diesel? Better hope there’s enough raw material to make it