A container ship sailing from Shanghai to Kaohsiung, Taiwan, travels just 600 nautical miles. A container ship sailing from Shanghai to Los Angeles travels 9.5 times farther — 5,700 nautical miles — and incurs dramatically higher fuel costs. And yet, according to Xeneta, current long-term contract rates for these two completely different trades are now roughly the same, at around $2,000 per forty-foot equivalent unit.

Contract rates on the short-haul run between China and Taiwan have surged since the beginning of this year, according to Xeneta. The culprit: geopolitical risk.

“It’s quite fascinating: $2,000 from China to Taiwan, the same as going across the biggest ocean in the world. One has to think about that,” said Erik Devetak, chief product and data officer for Xeneta, during a company presentation Tuesday.

And while the China-Taiwan situation is a very specific case, geopolitical tensions are escalating globally. What’s happening in this ocean trade, if ever mirrored in a much larger lane, could have significant implications for future global supply chain costs.

“This situation [China-Taiwan rates] is very idiosyncratic … but we’re going to see a lot of this,” Devetak said. “Geopolitics is going to make a difference in the future.”

China-Taiwan vs. China-Japan rates

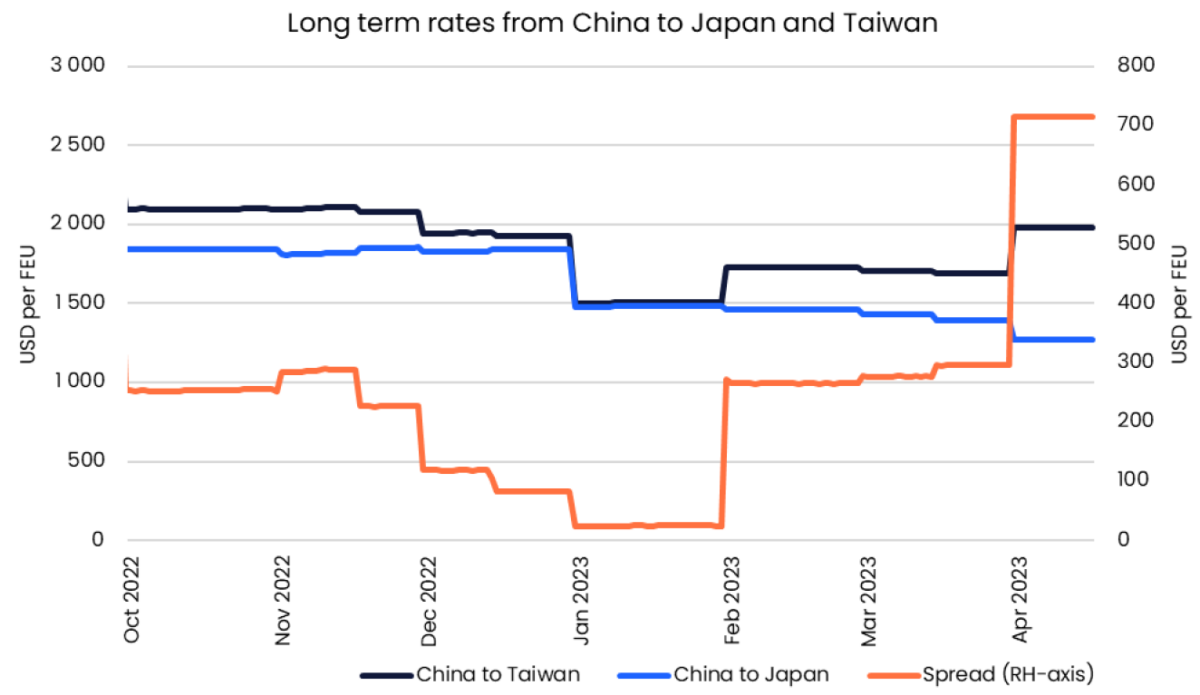

Highlighting the degree of recent moves in long-term rates, Xeneta compared two intra-Asia lanes: China-Taiwan and China-Japan.

“At the start of this year, the rates were basically equal. You were paying the same to Japan as you were to Taiwan. Now the two have moved in clearly quite different directions,” said Xeneta market analyst Emily Stausboll.

“The spread between them is increasing. It has increased to almost $750 [per FEU], which is about half the rate you’d be paying just to get into Japan,” she said.

“It’s not quite the same in the spot market,” Stausboll continued. “The spot market spread is increasing, but not to this extent, largely due to the fact that this is a trade that is at the seat of geopolitical risk.

“When you’re looking at doing those long-term contracts, that risk is much heavier than it would be on the spot market with that shorter time scale where you’re more certain of how things are going to go.”

According to Devetak, “There are risks of disruptions, from military exercises and so on. That risk is more of an unknown long-term risk, so the longer the contract, the more risk you’re taking. I think we are starting to see ocean carriers systematically take geopolitical risk into consideration when pricing long-term contracts. Going for a long-term contract into Taiwan, that carries risk.

“I also wonder how geopolitics will affect the length of the contract people are willing to take, because with a more uncertain world, in terms of geopolitics and therefore also indirectly in terms of supply chains, longer-term commitments potentially become less appealing to the supplier,” he added.

Spreads narrow, except for Taiwan

Widening spreads in freight rates between various port pairs were commonplace during the COVID-era boom, but now they’re shrinking. The spread of the China-Taiwan rates versus other port pairs is an outlier, underscoring the role of geopolitical risk.

“We’ve seen it moving in the opposite direction to what we’ve seen in other trades, where they’ve really been coming down,” said Stausboll.

“If you look a while back, between different countries in the Far East exporting to the U.S. or North Europe, you see that the rates out of China were much lower than the rates out of Japan and Korea and Taiwan. Those spreads are really now falling back to where they were before the pandemic. In contrast, this one is increasing.”

Devetak explained, “In the past, the spreads have been really driven by [ocean transport] capacity constraints. That was the driver until recently. The driver of spreads this year is very different. It is definitely not capacity. Even in intra-Asia, where demand has picked up more compared to the forecast, there is not a capacity constraint.”

Stausboll said, “Spreads are generally coming down. It’s only in trades where there’s something more specific going on where we see the opposite happening.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- China-Russia vs. US-EU: How global shipping is slowly splitting in two

- Container shipping sees signs of a bottom (at least, for now)

- US imports bounce back in March despite dwindling China cargo

- US imports from China falling faster than from other countries

- Global trade at the crossroads: Risks from geopolitics, inflation loom

- Saber-rattling in Taiwan Strait stokes new supply chain threat