What’s the single most important concentration of infrastructure keeping America supplied with goods? The Los Angeles/Long Beach port complex, which handles around 40% of the country’s containerized imports. What’s the second most important? One could make a strong case for the expanded Panama Canal.

America could never have handled the historic import deluge of the past two years if Panama had not built the third set of locks, the larger “Neopanamax” locks that debuted in 2016 and brought much higher-capacity container ships from Asia to East Coast and Gulf Coast ports.

The Panama Canal has been one of the big winners of the COVID-era shipping boom. But now, the pace of growth is slowing, mirroring a trend seen across much of global trade, and the canal is feeling more effects from the Ukraine-Russia war and China’s COVID lockdowns.

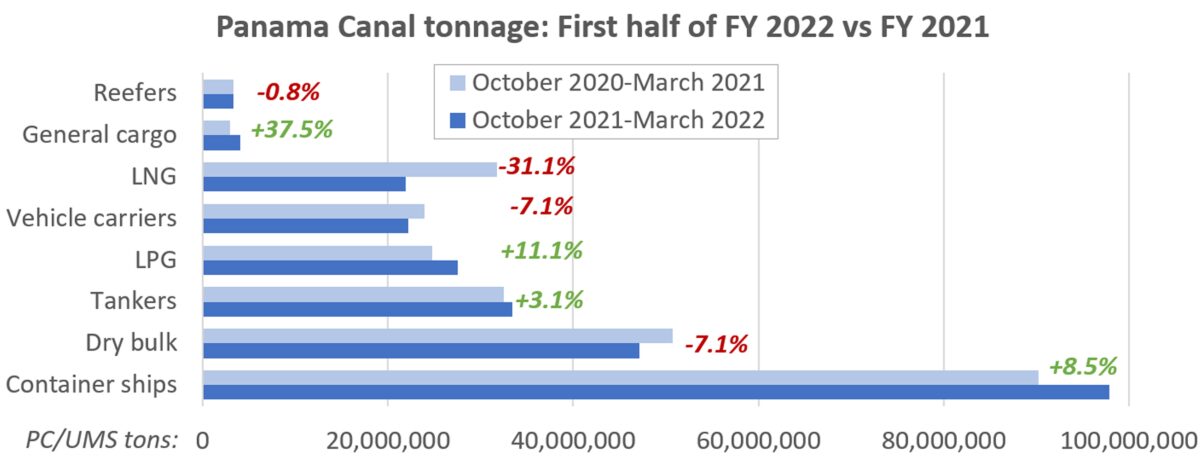

The waterway handled its highest ever shipping flows in fiscal year 2021, which ended in September. Panama Canal Universal Measurement System (PC/UMS) net tonnage rose 8.8% versus FY 2020. In the first half of FY 2022, between October and March, PC/UMS net tonnage rose 0.8% from the same period a year before. Container-ship PC/UMS tonnage rose 8.5% and liquefied petroleum gas tonnage increased 11.1%. Offsetting those gains, liquefied natural gas carrier tonnage plunged 31.1%.

“I’m still confident we’ll do as good as last year [overall], if not better,” Ilya Espino de Marotta, deputy administrator of the Panama Canal Authority (ACP), told American Shipper.

East Coast trend boosts Panama Canal

“In terms of containers, we have continuously seen an increase,” said Silvia Fernandez de Marucci, the ACP’s manager of market analysis. “We had a few months in the beginning [during the U.S. lockdowns] when traffic actually declined slightly. But it rebounded quickly. We have seen increases in traffic since July 2020.”

The old locks restricted container ships to a maximum capacity of about 5,000 twenty-foot equivalent units. The Neopanamax locks allow passage of ships with 15,000-TEU capacity.

According to The McCown Report, East/Gulf Coast ports handled 49% of total U.S. containerized imports in March. Pre-canal expansion, they were handling closer to a third. McCown’s data shows a sustained advantage for East/Gulf Coast ports after the Neopanamax locks opened, a shift back toward West Coast ports in the first half of last year at the height of COVID-era demand, then a reversion toward East/Gulf Coast services since then.

Marucci said that last year’s surge in West Coast traffic did not come at the expense of container volumes through the canal. Even as ships piled up off Los Angeles/Long Beach, container-ship transits in Panama rose. And with carriers’ shift toward East/Gulf Coast ports this year, transits are increasing further. “In March our transits for container ships increased 10% [year on year],” she said.

But it’s not all positive for containers.

COVID lockdowns in China will have near-term effects on canal volumes, admitted Marucci. “We don’t know what’s going to happen with the COVID situation in China but we think that we will feel a decline in April and maybe May. Then after China reopens, I think there’s going to be a flood of merchandise arriving to both coasts.

“We are also looking at many factors that are impacting not only traffic through the canal but trade overall. We’re looking at inflation rates and the increase in bunker [marine fuel] prices. It’s very volatile. We are not sure how the consumer is going to react to this inflationary pressure and how demand is going to behave.”

War slashes LNG transits

When Panama decided to go forward with the expansion project in 2006, it was focused on preserving its container shipping business. At that time, America imported LNG, it didn’t export it. Ten years later, when the expanded locks opened, America had switched to an LNG exporter, with Asia as a major buyer. The new locks allowed passage of LNG carriers headed west. The canal had chanced upon a major new business.

The recent downturn in LNG carrier transits began last fall, when the price of LNG in Europe rose above the price in Asia. LNG shippers could earn more arbitrage profit by selling U.S. gas in Europe.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine, putting Europe’s pipeline natural-gas supply at risk. That is pulling even more U.S. cargoes across the Atlantic and away from the canal. And the U.S. and the EU have committed to pursue supply arrangements that could make trans-Atlantic flows more permanent.

Commodity data provider Kpler compiles data on total U.S. LNG export volumes and the portion of those volumes that transit the Panama Canal. While ACP data only goes through March, the Kpler data shows that the canal had another very bad month for LNG transits in April. Kpler’s data shows that total monthly U.S. LNG exports rose 31% from 5.36 million tons in June 2021 to 7.03 million tons in April, but the share going through the canal fell from 43% last June to just 13% last month.

When will US LNG shift back to Asia?

“We have seen a drop in [LNG] traffic,” said Marucci. “There were 24 transits in March versus 38 in March 2021. There is a lot of uncertainty with what is happening with Ukraine and Russia. And we do believe this may be a more permanent thing favoring Europe because of the support the U.S. is offering to Europe, and the geopolitical situation with Russia, even if prices in Europe [and Asia] get closer to each other and the netback [for U.S. sales to Europe versus Asia] is reduced.

“But we have seen other market segments compensating for the drop in LNG,” she emphasized, pointing to strength in transit demand for container shipping and LPG shipping.

Also, U.S. LNG exports may turn back toward Asian buyers with contracted supply in the second half, meaning more LNG carrier transits via the canal.

Jon McDonald, senior analyst at Poten & Partners, said during a recent online presentation: “Europe imports continue at high levels … [but] there is really not enough supply for Europe to continue all year and still ensure that Asia has the volume it needs. Northeast Asia needs to rebuild inventories ahead of the winter and that should draw more cargoes to the region starting in the summer.”

Kristin Holmquist, forecasting manager at Poten, affirmed, “Europe has been taking a lot of gas at the expense of some Asian countries and Asia will need to reenter the market.”

War likely to boost bulker transits

The Ukraine-Russia war may affect transits in another shipping sector as well: dry bulk. Unlike the case of LNG shipping, this one would be positive for transit volume.

Container shipping is the canal’s largest segment in terms of PC/UMS, which measures ships’ volumetric capacity. But dry bulk is by far the largest segment in terms of cargo tons, more than double containerized cargo. Most of the dry bulk cargo crossing the isthmus is agribulk shipped from the U.S. Gulf to Asia: wheat, soybeans, corn and sorghum. (Dry bulk carriers mainly use the old Panamax locks because most grain terminals in the U.S. and Asia can’t load and unload ships larger than traditional Panamax-size bulkers.)

The grain trade has started out slow in FY 2022. In the first half, both dry bulk transits and PC/UMS tonnage are down 7%. But Marucci expects flows to pick up due to the war.

“Ukraine used to provide China with corn and now they’re not able to. We have seen large purchases of corn by China from the U.S.,” she said.

LPG carrier transits stay strong

Meanwhile, LPG shipping continues to play a key role in canal cargo flows — and the COVID-era consumer boom added even more strength. “They are the No. 2 users of the Neopanamax locks in terms of transits,” said Marucci.

As with LNG shipping, LPG shipping became much more important to the canal after the Neopanamax locks debuted.

U.S. exports of LPG — propane and butane — transit the canal en route to Asia in vessels known as VLGCs (very large gas carriers; ships with capacity of around 84,000 cubic meters). As soon as the expanded locks opened, almost all U.S.-Asia VLGC traffic switched from the Cape of Good Hope route to the shorter Panama Canal route.

“VLGCs have been very strong in the past two years. I think this is going to continue because LPG is mainly used in China for petrochemical production,” said Marucci.

U.S. propane cargoes are shipped aboard VLGCs to Asian propane dehydrogenation plants for the creation of propylene, which is used to produce polypropylene, which is in turn used to manufacture plastic.

The more goods Americans consume, the more plastic Asia churns out. “As we see the dehydrogenation plants continue to grow, the LPG trade is going to continue,” said Marucci.

Still at only 70% capacity

Panama Canal traffic has risen amid America’s consumer boom and is up around 60% since the Neopanamax locks opened. Yet the canal is still nowhere near its ceiling. “We are at about 70% of capacity. We still have room to grow,” said Marotta.

The ACP is tweaking operations to add even more capacity. Last June, it increased the maximum allowable ship length from 1,205 to 1,215 feet. Since October 2018, it has been reducing LNG carrier transit restrictions as it becomes more comfortable with operational safety. Now, the canal is looking to expand the maximum allowable ship width.

“We’ve been approached by the industry to allow wider beams,” said Marotta. “We’re analyzing a new fendering system that would allow us to do that.”

Add up all these changes, she said, “and the growth [potential] would even be a little bit higher than 30%.”

More water, then a fourth set of locks?

The ACP continues to invest in infrastructure, said Marotta. It’s buying 10 new hybrid-power tugs with an option for 10 more and investing in electric vehicles, maintenance, digitalization and facilities consolidation.

But the biggest move by far is a multibillion-dollar project to increase the canal system’s water supply. The canal faced transit constraints due to a drought in 2019 and 2020. Rain has kept water levels high in 2021 and 2022.

Marotta said that the ACP signed a contract with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in November to develop the project. “By 2024 we should have the project or projects defined, which will then go out to bid. We’re hoping to secure the quantity of water we need by 2028, or at least from some of the projects if there’s more than one.”

After that mega-project comes the even bigger question: Will the expanded canal need to be expanded yet again with a fourth set of locks?

“When we secure the water, then we will see if there’s enough demand to build a fourth set of locks,” responded Marotta.

“If it’s ever needed, we did leave a footprint area [when building the Neopanamax locks]. But for now, there are other strategies to increase the capacity of the existing infrastructure. The fourth set of locks is not in the short-term pipeline.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Despite rising risks, shipping lines on track for another record year

- Shanghai lockdown is not causing global supply chain chaos (yet)

- Container shipping at the crossroads: The big unwind or party on?

- Retail boss warns on supply chain, likens demand risk to ‘Big Short’

- How invasion of Ukraine could ease shipping logjam off US ports

- Biden-EU energy pact: LNG shipping game changer or wartime hype?

- Armada carrying US LNG heads to Europe, but it won’t be enough

- Shipping isn’t waiting for sanctions. It’s refusing to move Russian cargo