Planning to import goods from Asia by ocean and sell them in America this summer? Better act fast. The trans-Pacific cargo move can now take over three months. According to multiple sources, average transit times have risen to double pre-COVID levels — and they’re still increasing.

Methodologies and data sources differ, so time estimates vary. But each dataset shows the same trend: With every passing month, more vessels, container equipment and goods inventories are getting waylaid in the Pacific.

Flexport

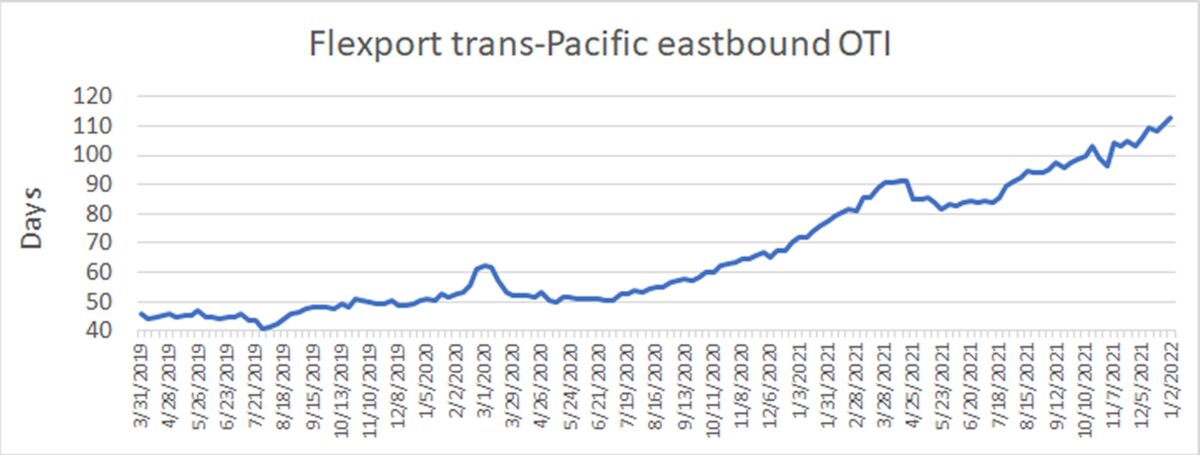

Flexport launched its weekly Ocean Timeliness Indicator (OTI) in early December. The OTI uses data from Flexport’s freight forwarding customers back to March 2019, measuring the time from the cargo-ready date at the exporters’ gate to the date when products leave the destination port (i.e., the landside transport time from the factory to the port in Asia, the Asian port wait, the ocean journey, and the North American port wait). The OTI is an average for loads from all Asian countries to all North American ports on any of the three coasts.

Flexport’s Asia-U.S. OTI reached an all-time high of 114 days last week. That’s 41 days or 57% higher than at the same time last year, and 63 days or 125% higher than at the same time in 2020, pre-COVID.

A shipment time is not included in the average until the import cargo leaves the U.S. port, meaning the indicator is retrospective. Goods included in the average in the first week of January might have left an Asian factory in early October, at a time when the queue of waiting ships off Los Angeles/Long Beach was around 40% smaller than it is now.

Phil Levy, chief economist of Flexport, explained the value of the OTI in an interview with American Shipper. “It does speak in terms of days, and in that sense it’s supposed to give a general idea of the magnitude shippers have to deal with. But it’s not a precise, forward-looking estimate of how long it will take you to get from your factory in Vietnam to Vancouver, for example.

“This is intended as a straightforward and transparent measure of how severe the crisis is,” he said. “You see a lot of things that jump around and other fleeting measures. You might say, ‘Hey, I got a great spot rate out of Yantian so I guess the crisis is over’ or ‘There was stuff on the shelves when I went shopping yesterday so I think we must be OK.’ But the OTI is something that is fairly consistent, you can see it over time, and you can see the degree of variability over time. You can see that these are dramatically longer times than we’ve had before — and they haven’t backed off yet.

“Let’s suppose the supply chain fairy waved a wand and solved all of these problems and we went right back to the old shipping times of the pre-COVID era again. What would the ‘all clear’ look like? You wouldn’t see an immediate drop because it would take awhile for things to sort out [due to the OTI’s retrospective nature]. But you should start to see this trending down as each stage [Asia factory to ships/ocean/U.S. port] moves faster. And we haven’t seen that yet. If this resolves, you should see something very different here.”

Freightos

Another measure of trans-Pacific shipping duration is produced by Freightos. It uses data since October 2019 from bookings on its Freightos.com marketplace, including both full container load (FCL) and less than container load (LCL) business.

The average monthly transit time is measured from China to U.S. ports, with the majority going to the West Coast ports. The delivery times are measured on an end-to-end basis, generally warehouse to warehouse.

Freightos calculated that it took an average of 80 days in December for trans-Pacific cargo, with FCL at 72 days and LCL at 82 days. The average transit time is 51% or 27 days higher than in December 2020 and 86% or 37 days longer than in December 2019, pre-COVID.

Shifl

Yet another dataset is produced by Shifl. This data tracks the ocean transit time of ships from when they leave major Chinese ports (Ningbo, Qingdao, Shanghai, Yantian) to their arrival in Los Angeles/Long Beach.

As of the first half of December, Shifl calculated that the transit time was 34 days, more than double the pre-COVID average of 16 days and about two weeks more than transit times in the middle of last year.

The second-half rise in the measures published by Shifl, Freightos and Flexport mirror the increasing number of container ships waiting offshore for berths in Los Angeles and Long Beach. According to data from the Marine Exchange of Southern California, an all-time high 105 container ships were waiting for berths on Thursday and Friday, with 103 waiting as of Tuesday.

Sea-Intelligence

The difference between the on-the-water data from Shifl and the end-to-end data from Flexport and Freightos confirms how much time is being lost at terminals on either side of the ocean.

Sea-Intelligence has developed an index, using data from carrier HMM, to quantify the level of terminal congestion on the North American side of the equation. That index has doubled over the past year.

Alan Murphy, CEO of Sea-Intelligence, warned this week: “It seems that there is no sign of imminent improvement. All available data shows that congestion and bottleneck problems are worsening.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- New year brings new all-time high for shipping’s epic traffic jam

- New index measures supply chain pressure — and it’s really high

- 2021’s top shipping stories: From Ever Given to epic California port pileup

- By the numbers: Shipping’s unparalleled year in 10 charts

- Escape from LA: More container business flees to East Coast

- Los Angeles import volume sinks as shipping traffic jam worsens