Last week, Maersk management announced that the company was suspending its share buyback program and cutting its dividend by 88%, signaling the end of an era when managing and deploying an enormous excess of capital was the top concern for the shipping line’s executive team. Maersk’s stock price dropped by approximately 16%. Now that the company’s pandemic-era bonanza is well and truly over, it’s time to take a retrospective look at how Maersk invested its cash when profits were pouring in by the billions.

During the pandemic when goods demand soared, transportation capacity tightened, and logistics infrastructure groaned under the strain of too much volume, transportation providers in all modes made hay while the sun was shining.

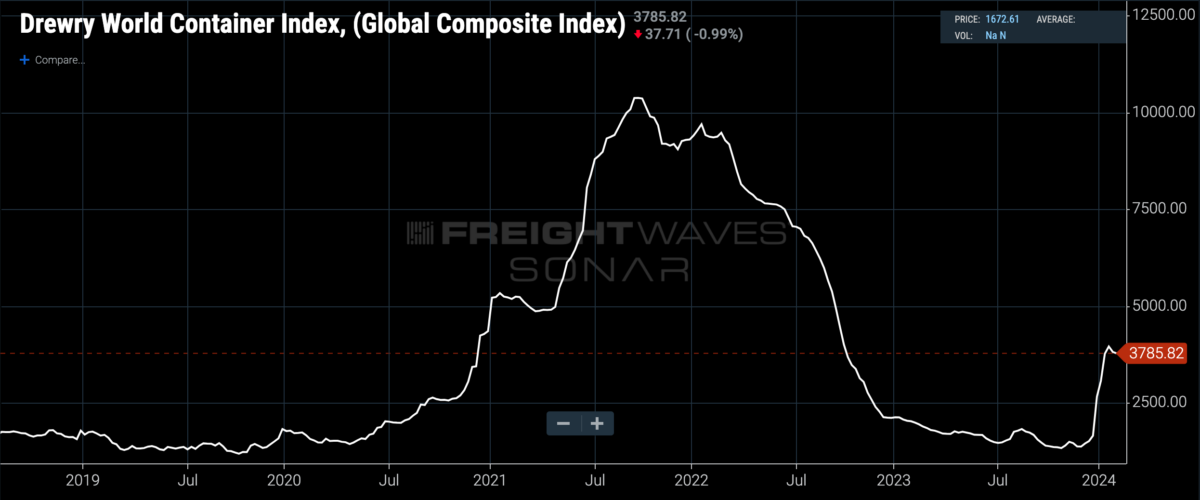

Maersk, the Danish container shipping giant and now the second-largest steamship line in the world, was no different: When trans-Pacific spot rates shot past $20,000 per forty-foot equivalent unit in some instances, Maersk raked in a windfall of historic proportions.

As container rates climbed, so did Maersk’s profits. For reference, in 2017, Maersk lost $1.1 billion; in 2018, a strong year for transportation, Maersk generated $3.2 billion in total profit. 2019 was a lean year, and Maersk lost $44 million. Then the pandemic hit. Profits in 2020 totaled $2.9 billion, a year that saw disruptions to operations including lockdowns, stranded ships and shuttered ports. In 2021, Maersk’s earnings jumped to $18 billion as it reaped a full year of high spot rates and repriced its contract business; in 2022, profits peaked at $29 billion. But then as demand receded, so did prices — quickly. Last year, Maersk generated $3.9 billion in earnings, and now the company says it’s worried about profitability.

Søren Skou, Maersk’s CEO from 2016 to 2022 (he had been CEO of Maersk Line since 2012), and then Vincent Clerc, chief executive officer from January 2023 on, were faced with a unique situation in the containership line’s history: how to invest tens of billions of dollars in excess profit productively to earn an acceptable return for shareholders. To put it mildly, this is not a situation that container line executives were accustomed to finding themselves in — as McKinsey has noted in its widely cited reports on the state of the container industry, the mode has been a net consumer of capital for decades.

Some back-of-the-envelope math puts a number on the scale of the problem. Let’s assume that 2018 was a standard pre-pandemic “good year” with approximately $3 billion in earnings. If Maersk had earned $3 billion per year in 2021 and 2022, profits would have totaled $6 billion for the two-year pandemic peak. In reality, profits totaled $47 billion, and subtracting the $6 billion we figured for “normal” good years, that equates to $41 billion in what we can call “excess” profits for the two-year period of 2021 and 2022.

Most executives in charge of an asset-heavy transportation provider would be tempted to burn through the money by buying more assets, grabbing more market share and building density on its most profitable, important lanes. The problem is that container shipping has been plagued by a structural glut of overcapacity for years. Larger containerships operate at a lower cost per twenty-foot equivalent unit and are more profitable to run, so smaller vessels tend to be replaced by larger ones.

But then there are the state-owned enterprises in Asia, like China Cosco, whose orderbook China’s government uses to stimulate its domestic shipbuilding industry and artificially subsidize its export economy. What makes sense for China — keeping its shipbuilders busy and making it cheap for manufacturers to export their goods — plays havoc with the global container market, which is composed of players who generally want to charge money for their services and earn a profit.

So the real dilemma for Maersk’s executives was a slight but significant variation on the earlier statement of the problem: How does the company deploy $41 billion in excess profits without increasing the size of its containership fleet? To be clear, this problem wasn’t unique to Maersk — all containership lines faced the same issue, albeit with cash hoards and fleets of different sizes.

The solution was threefold: Let cash balances rise, return cash to shareholders, and invest in large strategic acquisitions, particularly in inland logistics operations that enjoyed a historically higher margin profile than ocean container shipping.

First, the cash: From 2016 to 2020, Maersk carried approximately $3 billion-$4 billion in cash on its balance sheet, but it let its reserves run up to $12.1 billion in the first quarter of 2022, according to company filings.

At the same time, Maersk was shoveling cash back to its shareholders, far more than it ever had before. It announced a $12 billion stock buyback plan that equated to $3 billion per year from 2022 to 2025. Dividend expenses ramped dramatically: In 2020, Maersk paid out 7 cents per share, or approximately $520 million in dividends. The next year, in 2021, that number more than doubled to 16 cents per share, or $1.1 billion total. (Note that Maersk pays out its annual dividends in April, largely based on the prior year’s earnings.) In 2022 and 2023, dividend payments ballooned to $1.30 per share and $6.9 billion, and $2.20 per share and $10.9 billion, respectively.

For the two peak pandemic years, then, Maersk returned approximately $24 billion to shareholders in the form of stock buybacks and dividends, an explicit admission that the management team had no real way of generating an attractive, sustainable yield by investing the capital in the business.

In 2022, Maersk spent approximately $5.9 billion on three significant acquisitions. In May, Maersk paid $1.7 billion for Pilot Freight Services, a third-party logistics provider based in the United States with a large air cargo forwarding business and an extensive brokered truckload network that services freight at 87 stations and hubs in the U.S. The deal more than doubled Maersk’s inland logistics real estate footprint in the U.S. The next month, Maersk bought Senator International, a German air cargo forwarder, for $644 million. And then in August, Maersk leaned into the pandemic economy, acquiring LF Logistics, a Hong Kong-based e-commerce provider with 223 warehouses across Asia, for $3.6 billion.

The 2022 acquisitions fit well into Maersk’s overall strategy of pursuing market share as a global, mode-agnostic integrator of logistics services. Whether the deals were well timed or well priced is another matter: Note how “Logistics and Services” revenue at Maersk declined from its fourth-quarter 2022 peak of $4.18 billion to $3.54 billion in the fourth quarter of 2023. That decline was an inevitable result of falling freight rates across modes and geographies generally and to be expected. Yet it prompts questions about the wisdom of buying logistics assets at the very top of the market at peak valuation multiples, when both top-line revenues and profitability were set to fall precipitously.

The foregoing recap of Maersk’s pandemic finances should make it clear, though, that the company really had no choice but to buy aggressively in inland logistics when it had the cash and opportunity to do so. Price sensitivity was probably not its primary concern, although FreightWaves is aware of several other billion-dollar deals that Maersk shopped which ultimately fell through as freight market conditions deteriorated in 2022 and 2023.

Maersk’s stock price peaked at approximately $18.40 per share in January 2022 and has been cut in half since then: On Tuesday, shares were fetching $7.70 apiece on the Nasdaq Copenhagen exchange.

The company’s revenue and earnings trends have finally come full circle since the pandemic, but the story hasn’t completely played out. What remains to be seen is what kind of operating leverage and earnings lift Logistics and Services will provide to the bottom line once the freight market hits another cycle peak. If Skou’s bets pay off, Maersk’s earnings should reset at a higher level than before.