Pressure is being let out of global freight markets as demand falls and lower volumes in a variety of modes are more easily handled by the capacity and infrastructure built up during the last two years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Transportation rates in several modes, including truckload and ocean container, are falling as demand deteriorates and capacity loosens.

The softness started with American consumer demand, which has been wobbling and running out of momentum as the effects from fiscal stimulus faded and inflation took hold in the economy. Two quarters of negative GDP growth — coupled with very high import levels — depressed the demand for transportation capacity and caused trucking spot rates to plummet.

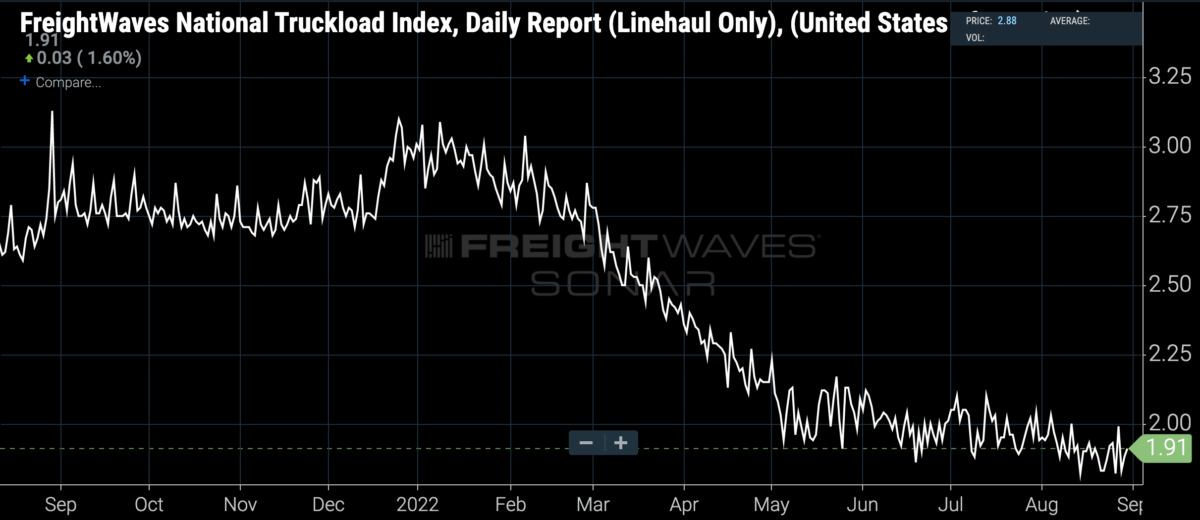

During what should have been the traditional summer bull run, linehaul rates stabilized momentarily but are now grinding back downward, even as diesel prices climb again.

FreightWaves’ Outbound Tender Rejection Index, which measures the percentage of truckload shipments rejected by carriers, fell Tuesday to a new cycle low of 5.43%. (Wednesday’s number of 5.44% isn’t meaningfully better.) Two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth and high inflation, coupled with the entry of huge numbers of small carriers in the market, have shifted the supply-demand balance in domestic trucking.

When carriers feel that they have few attractive options in the freight market, they take the loads they can get, rejecting fewer shipments and accepting more from their contracted customers. Low tender rejections indicate a lack of carrier pricing power; low rejections will also push spot rates lower until they become so attractive to shippers that contract rates too come down.

Today, the largest five trucking markets — Los Angeles, Dallas, Atlanta, Chicago and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania — all show very loose trucking capacity. Only Harrisburg (OTRI.MDT) is rejecting a significant amount of outbound freight at 8.36%.

Los Angeles is particularly soft, rejecting just 2.2% of outbound loads, and conditions there look to become even leaner for truckload carriers. When consumer buying pressure eases domestically, shippers replenish their inventories less urgently, and traffic from distribution centers to retail locations slows. Eventually purchase orders to upstream suppliers are adjusted downward, and months later imports start to slow.

U.S. third-party logistics providers are concerned about volume risk and seem willing to sacrifice rates to secure volume.

An executive at a publicly traded U.S. transportation provider told FreightWaves Wednesday morning that his team had engaged in multiple rate-reduction exercises with single customers and that about half of his firm’s top 25 customers had asked for rate reductions. After cutting revenue per load by 20% from its peak in February, the provider has managed to eke out 10% year-over-year volume growth, but the situation “feels like a typical race to the bottom.”

An analyst at a top 10 freight brokerage told FreightWaves: “Our view is that the high-volume, ‘live pick, live drop’ contract freight is going to see contract rates down into next year.

“I expect national average rates to fall until the gap between spot and contract closes,” the analyst added.

FreightWaves analyst Henry Byers called for a dramatic drop in U.S. imports based on ocean container bookings data that we saw in June: That drop is now materializing in a major way.

According to the Port of Los Angeles’ Signal Port Optimizer, the TEU volumes arriving this week are down 12.44% from last week, and next week will experience a further 10% drop from this week’s volume. Next week, the United States’ largest port expects volumes to fall 25% year over year.

The ocean container bookings data in Container Atlas confirms that inbound ocean container volumes to the United States will continue to deteriorate for months to come. The chart below displays booking levels from all ports globally to the U.S., with the shipment tied to the date it was booked with the carrier. Depending on the port of origin, those volumes will hit American shores in 30-70 days.

The drop in inbound ocean containers is a long-delayed knock-on effect taking place months after the U.S. truckload market rolled over. It takes that long for purchase orders to be adjusted, suppliers to reduce shipment sizes and those reductions to be felt at U.S. ports. But now that it’s here, Los Angeles, considered the “beating heart” of the U.S. truckload market, will likely see negative year-over-year inbound container volumes for the remainder of 2022.

The capacity picture is still fuzzy: There is data showing high numbers of carrier failures, as well as anecdotal reports from insurance providers experiencing record months in terms of new policies issued. What seems to be clear is that small carriers that entered the market during peak asset prices — prices for 3-year-old trucks peaked at $143,000 in April — are experiencing financial distress, while more carriers continue to enter the market, potentially with somewhat lower fixed costs.

For those reasons, it’s unwise to assume that the bottom for the U.S. truckload market is already in. Be prepared for further downward pressure on rates, especially if you’re a transportation provider with a mandate for volume growth.