Just as the cost of gasoline has risen at the local pump, so too has the cost of marine fuel at the ports. The world’s container ships, tankers and dry bulk carriers are spending more to cross the oceans than they have since 2013.

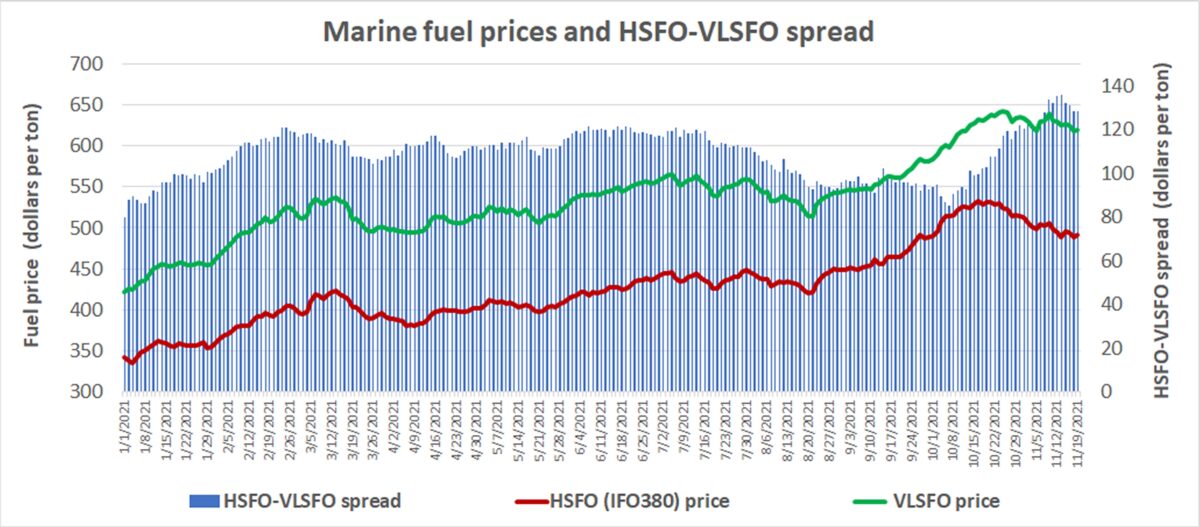

According to Ship & Bunker, the price of 0.5% sulfur fuel known as VLSFO (very low sulfur fuel oil) at the world’s top 20 ports averaged $619.50 per ton on Friday, up 47% from the beginning of this year. The top-20 VLSFO average hit a recent high of $639 per ton on Nov. 10.

Most of the world’s commercial ships switched to VLSFO as of Jan. 1, 2020, to comply with the so-called IMO 2020 regulation. Prior to that, most ships burned cheaper 3.5% sulfur fuel known as HSFO (high sulfur fuel oil).

Vessels equipped with exhaust-gas scrubbers can continue to burn less expensive HSFO under the IMO 2020 regulation. The bigger the spread between HSFO and VLSFO, the more valuable it is to have a scrubber.

That spread is now as high as it’s been since the initial days of the regulatory changeover.

Ship & Bunker estimated that the price of HSFO at the world’s top 20 ports averaged $491 per ton on Friday, up 43% from the beginning of 2021. Both VLSFO and HSFO are up sharply this year, driven up by rising Brent pricing. But as oil prices have fallen in recent weeks, HSFO pulled back more than VLSFO, pumping up the HSFO-VLSFO spread, known as the “Hi-5 Spread.”

According to Braemar ACM Shipbroking, the HSFO-VLSFO spread in Singapore “has averaged $151.50 per ton so far in November, the highest level since early 2020.”

Braemar attributed lower HSFO pricing to a drop in its use for power generation, given the end of the summer season in the Middle East and Southeast Asia.

Scrubber installations continue to rise

The initial wave of installations in preparation for IMO 2020 was followed by a period of uncertainty. At certain points in 2020, the Hi-5 Spread fell to $50 per ton, undercutting the rationale for installations.

The current spread has swung the pendulum back toward more scrubbers.

Data from Clarksons shows that scrubber installations have continued to rise. There are now 82% more commercial ships with scrubbers in service than there were at the beginning of last year.

In January 2020, there were 569 crude or product tankers on the water with scrubbers. As of this month, there are 1,041, plus another 109 pending.

There were 816 dry bulk carriers with scrubbers in service in January 2020. There are 1,530 scrubber-equipped bulkers on the water currently, with an additional 69 scheduled.

The container segment is showing the biggest gain, given that container shipping has the largest orderbook and that it’s more cost-efficient to install scrubbers on newbuilds than retrofitting existing ships. Container shipping accounts for most of the future scrubber installations.

In January 2020, there were 408 container ships in operation that used scrubbers. Now, there are 913. And an additional 347 scrubber-equipped container ships are scheduled, according to Clarksons, 246 through newbuilds and 101 through retrofits.

How higher fuel costs impact shipowners

The rising cost of fuel has been one of the few blemishes in container lines’ quarterly reports. Maersk’s bunker costs jumped from $759 million in Q3 2020 to $1.42 billion in the most recent quarter. Container lines ultimately pass those costs along to shippers through bunker adjustment factors.

In tanker and dry bulk spot deals, the ship operator pays for the fuel. The ship operator’s fuel cost for the voyage is incorporated into the dollars-per-ton spot rate it charges the cargo shipper. Indexes translate the dollars-per-ton spot rate into a dollars-per-day equivalent, net of estimated daily fuel costs, meaning that rising fuel costs lower index values.

The tanker sector is in the midst of its worst year in decades. Tankers have been accepting rates well below cash breakeven (including both operating expenses and debt service). At this year’s rates, tankers with scrubbers don’t make more money than tankers without scrubbers — they lose less money.

Clarksons Platou Securities estimates that the cash breakeven rate for a 10-year-old very large crude carrier (VLCC, a tanker that carries 2 million barrels) is around $24,000 per day. A VLCC of that age with no scrubber was earning the equivalent of $10,400 per day as of Monday (i.e., losing around $13,600 per day). A 10-year-old VLCC with a scrubber was saving $6,700 per day on fuel by burning cheaper HSFO and earning $17,100 per day (i.e., losing $6,900 per day compared to the all-in breakeven rate).

In a profitable market like dry bulk, the use of scrubbers adds to the gains — after the cost of the scrubber is accounted for. According to Clarksons, a 10-year-old Capesize (a bulker with capacity of around 180,000 deadweight tons) without a scrubber was earning a spot rate equivalent to $32,200 per day on Monday, or $14,200 per day above the cash breakeven of $18,000. The scrubber-equipped Cape was saving $5,300 per day on fuel, bringing its take to $37,500 per day, $19,500 above breakeven.

Star Bulk (NYSE: SBLK) has been the most aggressive adopter of scrubbers among listed shipping companies, installing them aboard more than 100 ships. Given positive moves in the Hi-5 Spread, Star Bulk said last week that it expects to fully cover the cost of its scrubber installations by Q2 2022.

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Yet another worry: Price of ship fuel is now highest since 2014

- What $70+ oil means to container, tanker and dry bulk shipping

- Ship prices jump, spread widens. Scrubber revival nigh?

- How IMO 2020 turned into the Y2K of ocean shipping

- Coronavirus is decimating IMO 2020 ship-scrubber savings

- Platts debuts parallel IMO 2020 ship indices and the spread is huge