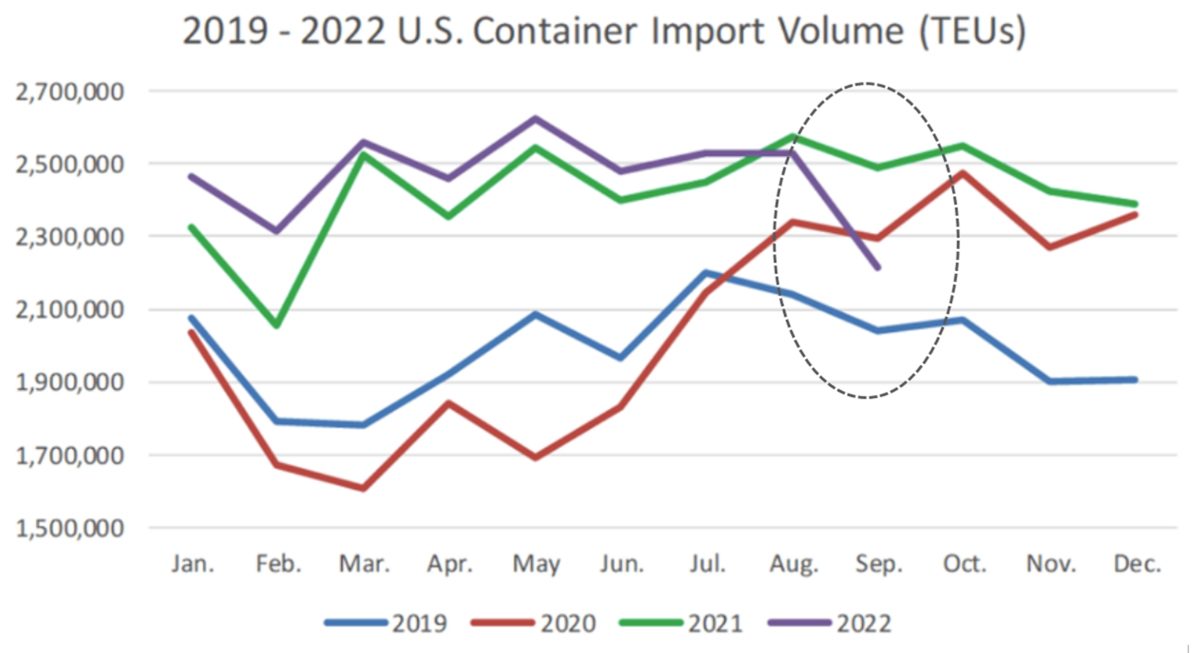

First came the pullback in spot shipping rates from their historic peak. Then came reports of plunging Asian bookings and mass retail order cancellations, with spot rates falling even faster. Now, all of this is finally showing up at America’s ports.

According to Descartes, which aggregates U.S. Customs data, inbound volumes to all U.S. ports totaled 2,215,731 twenty-foot equivalent units in September. That’s down 11% year on year and 12.4% from August.

Last month’s imports came in below September 2020 levels, albeit still up 9% from September 2019, pre-COVID. Imports this September were down 15.5% versus May, the month inbound volumes hit an all-time high, according to Descartes data.

September’s 313,311-TEU decline versus August was the steepest month-to-month drop recorded by Descartes since the 364,454-TEU plunge in February 2020 versus the month before, back when Chinese authorities first locked down Wuhan.

“We’ve had a pretty significant correction here,” said Chris Jones, executive vice president of industry and services at Descartes Systems Group, in an interview with American Shipper on Monday.

This is normally the time of year when imports seasonally decline — but not by this much. “There was an inflection, and it was a big one,” he said. “In some respects, this is not inconsistent with other years [pre-COVID]. It’s just more severe.”

If the usual seasonal pattern holds true from here, Jones added, imports “should slow down for the rest of the year.”

Descartes: Imports decline on all three coasts

This summer, overall U.S. imports remained stubbornly high, hovering near record levels even as West Coast volumes declined. West Coast losses were offset by East and Gulf Coast gains, reportedly due to shippers shifting cargoes eastward due to fears of West Coast peak season congestion and labor unrest.

Ports on all three coasts saw volumes drop versus August, according to Descartes. Most surprisingly, it found that imports fell 21.5% in Savannah, Georgia, from 285,341 TEUs to 223,966 TEUs.

Savannah, along with New York/New Jersey, has been one of the big winners of the eastward shift. Savannah posted record imports in August. It has had the country’s longest queue of waiting ships for months. As of Monday, ship-position data showed 35 ships still waiting. The presence of so many vessels offshore confirms there is no shortage of cargo waiting to be unloaded in Savannah, so how could its import numbers fall so steeply in September?

The answer appears to be: Hurricane Ian. Official Savannah numbers have yet to be released. A spokesperson for the Georgia Ports Authority (GPA) told American Shipper: “September volume was impacted due to Hurricane Ian and the suspension of vessel service for roughly three days. GPA has since been accommodating that volume, which will be reflected in October numbers.”

Meanwhile, official data released Tuesday by South Carolina Ports conflicts with Descartes data. South Carolina Ports said loaded imports were up 16% year on year in September, implying that Charleston import volumes were flat versus August, whereas Descartes said they fell 6.5% month on month.

Data from PIERS also conflicts with Descartes. PIERS data shows a 1.5% year-on-year increase in U.S. imports in September.

Volumes from China collapsing

According to Descartes, U.S. imports from China totaled 820,329 TEUs in September, down 22.7% year on year and 18.3% versus August. Declines from China accounted for 61.5% of last month’s drop compared to the month before.

“If you think about the lockdowns in China, some of those things have now had a chance to flush themselves out and you now see that in the numbers,” said Jones, noting the lag effect between the lockdowns and the import decline. “These Chinese numbers are way down.”

Commenting on the timing of the September plunge, Jones pointed to multiple lag effects between initial demand weakness and import data weakness, ranging from lags on the origin side to those at America’s ship queues. “Imports are a completely lagging indicator because of the lead times,” he emphasized. “These supply chains are so extended.”

Supply chain crunch not over yet

Declining import volumes should give terminals breathing room to clear out more containers from their yards in the months ahead. Even so, Jones agreed that “it’s too soon to declare victory” when it comes to the supply chain crunch.

Imports and consumer spending are still above pre-pandemic levels. Rail congestion remains high. Both import and empty container levels at terminals remain elevated.

As of Monday morning, there were still 103 container ships waiting offshore of North American ports. Waiting times off East and Gulf Coast ports remained over 10 days in September, according to Descartes. Meanwhile, there has yet to be a breakthrough in the West Coast port labor negotiations and the new rail labor contract still requires approval. (One union has just rejected the proposal.)

The complexity of the situation makes it very difficult for U.S. retailers and importers to plan ahead. “There’s too much and not enough,” said Jones. “Things like personal gaming systems come in the door and they’re out the door, while you have seasonal [goods] where you just get crushed.”

Overall, “consumption has not slowed down as much as people thought,” he continued. Importers “have to make bets and the longer the lead time [due to supply chain delays] the less accurate” those bets turn out. As a result, he said, “we’ll see some cases where too much inventory shows up and others where you can’t get enough of what you need.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Tidal wave of new container ships: 2023-24 deliveries to break record

- Shipping giant Maersk: ‘Significantly less demand’ but ‘no hard landing’

- If supply chain crunch is finally easing, why is inflation so high?

- Container shipping lines suddenly a lot less interested in renting ships

- Fall in container spot rates ‘much steeper,’ ‘less orderly’ than expected

- West Coast ports sink to lowest share of US imports since early 1980s