The past two months have offered a textbook example of just how much stock investors crave the volatility of ocean shipping spot markets.

Spot rates for very large crude carriers (VLCCs, tankers designed to carry 2 million barrels of crude oil) skyrocketed from $50,000 per day at the end of September to around $200,000 per day on Oct. 11, dropped back to $60,000 by mid-November and have now popped back above $100,000 per day. It’s hard to find other markets to bet on that gyrate to this extreme. Tanker stocks with exposure to these spot rates have surged in response.

This deep-seated focus on spot rates — not just among public and private investors but also among commodity charterers — could complicate plans to reduce the shipping industry’s carbon footprint in the years ahead, a move that will almost certainly require much more time-charter coverage.

Penalizing period charters

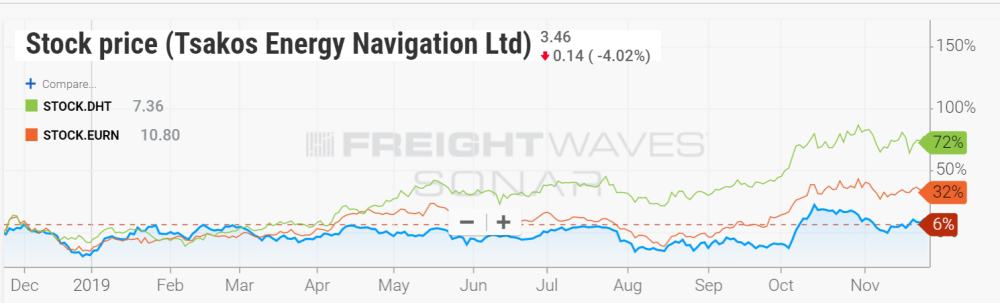

Investors react negatively when ship owners do not have enough exposure to soaring spot rates. Case in point: the stock of Tsakos Energy Navigation or TEN (NYSE: TNP), one of the largest tanker owners in the public market, which has lagged its compatriots, not just because it focuses on smaller vessel classes, but also because of its higher time-charter coverage.

The Nikolas Tsakos-led company appeared prescient when it pivoted to a long-term-charter-centric approach in 2016 at a time when competitors remained doggedly focused on the spot market. Spot rates collapsed and in 2018, TEN’s revenues topped the spot market by 40%. However, its conservative strategy didn’t boost its stock price.

With spot rates now rising, TEN executives went out of their way on the quarterly call on Nov. 26 to emphasize exposure to future upside as legacy time charters roll off, but their audience had dwindled. One informal test of investor interest is the Q&A session on quarterly calls. The Q&As on the latest calls for spot-exposed Euronav (NYSE: EURN) and DHT (NYSE: DHT) were long and heavily attended. The Q&A for TEN was embarrassingly brief.

Stifel analyst Ben Nolan said in a client note that TEN shares are currently trading at just 47% of their estimated net asset value (NAV), the market-adjusted value of the ships plus cash and contract values, minus liabilities. Nolan estimated that TEN’s peer group is now trading at 84% of NAV.

Another example of investors’ spot-centric focus is GasLog Ltd. (NYSE: GLOG), the liquefied natural gas (LNG) transport company led by shipping titan Peter Livanos.

GasLog previously had spot-market exposure through the so-called “Cool Pool,” a commercial cooperation agreement with Dynagas LNG and Golar LNG Ltd. (NASDAQ: GLNG). GasLog pulled out of the pool in June and put its ships on index-linked contracts that effectively capped both highs and lows.

LNG spot rates made headlines by hitting highs of $130,000-$140,000 per day in October as a large number of vessels were effectively tied up in floating storage. But GasLog executives conceded on a Nov. 5 conference call that the company’s contract rate ceilings were lower than that, limiting upside. Shares plunged. GasLog’s market capitalization has declined by $437 million since that call.

There are other examples of an anti-conservatism bias in public shipping stocks. In an interview with FreightWaves, Carlos Di Mottola, the chief financial officer of Italian-listed D’Amico International Shipping (Borsa Italiana: DIS), explicitly stated that his company’s stock was trading at a discount to NAV due to its higher period-charter cover versus its peers.

Period charters and carbon reduction

The issue of spot-versus-period employment should become far more important when shipping carbon-reduction regulations move forward.

Prior to the 1990s, bulk ocean shipping followed an “industrial” model wherein commodity shippers took vessels on multi-year long-term charters or owned the ships themselves. Since then, commodity shippers have primarily opted for spot voyage deals instead (albeit adding more long-term coverage when markets are sustainably frothy).

Martin Stopford, one of the leading intellectuals of the industry and the author of the industry bible “Maritime Economics,” has repeatedly argued at public events over recent years that shipping must revert to its industrial-shipping roots to take advantage of new technologies and tackle environmental challenges.

Michael Parker, global head of shipping and logistics at Citi, has voiced a similar argument in respect to pending carbon-emission requirements.

Parker is the chairman of the drafting committee of the Poseidon Principles. Under the Poseidon Principles, shipping banks handling around 20% of the industry’s senior-debt needs have agreed to benchmark their loan portfolio carbon intensities versus the targeted reduction trajectory endorsed by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The IMO’s target is to cut shipping’s carbon intensity by at least 40% from 2008 levels by 2030 and to reduce its greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions by 50% by 2050.

During the Capital Link event in New York on Oct. 15, Parker said the industry faces “the total re-engineering of the global fleet. The whole of the world fleet is going to change based on decisions to be made in the next three to five years by bodies like the IMO.”

Parker believes this will provide “oil companies with opportunities to enable the transition [to cleaner fuel] in the context of financing the shipping industry.” In other words, public oil companies could burnish their tarnished reputation with investors by doing so. Asked by FreightWaves after the panel whether he was implying a shift back to industrial shipping underpinned by long-term charters, he nodded in the affirmative.

At the Marine Money forum in New York on Nov. 13. Jeff Pribor, chief financial officer of tanker company International Seaways (NYSE: INSW), commented, “One thing that’s sort of quasi-insane about both dry bulk and tankers is that it’s an entirely speculative business in respect to newbuildings. As owners, we don’t have any choice but to make speculative orders if we’re to build new ships because we’re not offered the kind of long-term contracts that give a return on capital you would take.

“If this technological risk were to lead to someone like Shell or BP offering a sensible long-term contract for a newbuilding, it might be a move towards maturity for our industry,” Pribor added.

Resurrecting long-term charters

Long-term charters are commonplace in LNG and container shipping because new ships are very expensive and the cargo commitments are lengthy, in the case of LNG shipping, to serve liquefaction projects, and in the case of container lines, for provision of scheduled service.

Commodity shippers in the dry bulk and tanker markets have much more flexible requirements and are much more prone to spot deals. Dry and wet bulk shippers have largely turned away from the industrial shipping model over the past three decades because spot vessels have been overabundant amidst highly fragmented vessel ownership.

If commodity shippers are to someday commit to lengthy period charters or shared ownership to underpin expensive low-GHG newbuilding designs, it logically follows that long-term rates would have to be substantially higher to compensate ship owners for the risk, and in the case of public owners, to compensate investors (through, for example, a sustainably high dividend that offers better returns than competing non-shipping investments).

Long-term charter rates could not go higher to compensate for ownership risk until older on-the-water spot ships were removed from the market by future regulations. It they weren’t, older spot ships would undercut the pricing of newly built chartered ships.

The removal of on-the-water spot bulkers and tankers would only be possible in practice if the major nations of the world agreed to enforce IMO regulations that required these removals, despite the fact that this capacity reduction would significantly increase their economies’ cost of ocean transport.

Ironically, given current stock performance on Wall Street, the hypothetical low-GHG shipping model envisioned for the future would look more like Tsakos’ long-term employment model in 2016-18 and the conservative approach of GasLog, and less like the model of today’s high flyers DHT and Euronav. More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller