“These numbers are ugly. There’s no way around that,” admitted World Trade Organization (WTO) Director-General Roberto Azevedo during a press conference on Wednesday, upon the release of the WTO’s coronavirus forecast.

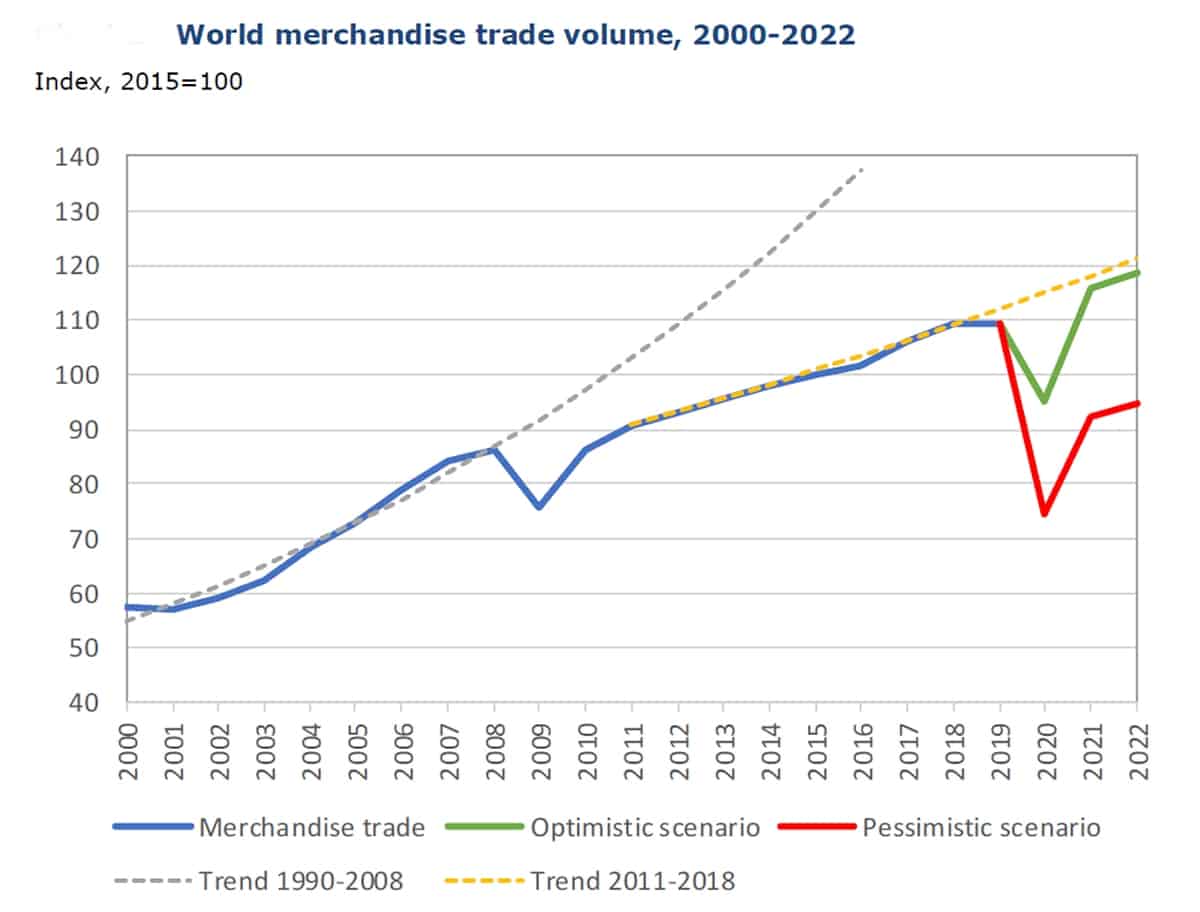

The trade organization outlined two potential scenarios: an optimistic V-shaped recovery in which world merchandise trade volume falls 12.9% this year and a pessimistic L-shaped pattern in which volume collapses by 31.9%.

“The optimistic scenario is about the same order [of volume decline] as the 2009 financial crisis, and the pessimistic one is about the same size as the Great Depression in the 1930s — but over one year, not three,” Azevedo said.

“This may well be the deepest economic downturn of our lifetimes,” he warned, conceding that that outcome could be even worse than the WTO’s pessimistic scenario. “If this [pandemic] is not brought under control and governments fail to implement and coordinate an effective response, the decline could be even higher.”

The good news, said the director-general, is that the world should bounce back from the coronavirus much more swiftly than from previous crises. After the 2009 financial crisis, merchandise trade never reattained its previous growth trajectory.

“The underlying causes are very different. The economic engine was in decent shape before the pandemic — the pandemic cut the fuel line. The Great Depression and the financial crisis were due to the fundamentals of the economy. This is a health crisis.

“Regardless of how steep the initial fall is, we could be back to full speed at pre-pandemic levels in one year or maybe two,” he maintained. “Theoretically, it should be easier to reconnect the fuel line to the engine.”

Keys to recovery

He believes the nature of the rebound will hinge on how quickly the virus is brought under control and on how governments respond via policy. “Businesses and households must believe that this is a temporary one-off economic shock, which will require fiscal, monetary and trade policy to all pull in one direction,” he said.

The danger is that trade policy will take a separate course, toward protectionism, where it was already headed prior to the outbreak. “Persistent trade tensions” led to a decline in merchandise trade during the second half of last year, said the WTO.

Azevedo acknowledged that the outbreak has severely affected global supply chains. In response, he said, “either supply chains will have to be diversified away from just one country or one region, or countries will bring production home and concentrate it within the borders of each country.”

The latter “would be the wrong response,” he insisted. “Closing borders and impeding trade will make it more difficult for investors and households to believe we’re back on track.” If they don’t, they’ll spend more cautiously, stunting future growth.

Merchandise trade reverts to precrisis levels next year under the WTO’s optimistic scenario. In the L-shaped scenario, it doesn’t recover and “it will remain well below the pre-COVID-19 trend line,” Azevedo said.

How trade relates to GDP

The WTO’s optimistic case assumes social distancing lasts only three months, with improved weather conditions easing the spread of the virus. The pessimistic case assumes mitigation measures persist throughout 2020 and until a vaccine is developed.

The V-shaped scenario assumes global GDP will fall 4.8% this year, the L-shaped scenario 11.1%.

An important indicator for container shipping is the ratio of world merchandise trade growth to global GDP — so-called “trade-to-GDP elasticity.”

A ratio over 1.0 means that merchandise trade — and thus container volumes — are changing at a faster rate than GDP. In good times, when GDP is rising, a ratio over 1.0 means that supply chains are globalizing and goods are being shipped by sea to a greater degree than economies are expanding.

But trade-to-GDP elasticity goes both ways. In a downturn, a ratio over 1.0 means trade is falling faster than the world economy. Furthermore, crises cause the ratio to surge as decreased demand reduces imports of durable goods and trade costs and transit times escalate.

The WTO calculated that in the 2009 financial crisis, merchandise trade fell 6.3 times faster than GDP. It forecasts that the ratio would be 3.6 in its optimistic coronavirus case and 5.3 in its pessimistic case.

During the 2009 financial crisis, the WTO explained, “reduction in demand was more concentrated in highly tradable durable manufactured goods,” i.e., the kind of items that fill containers.

There is also significant fallout for durable goods in the coronavirus crisis, especially for “sectors characterized by complex value-chain linkages, particularly electronics and automotive products,” said the WTO. However, the current crisis features a higher proportion of fallout for “non-tradable sectors … such recreation and accommodation,” thus a lower ratio of merchandise trade-to-GDP than in 2009.

The reason the ratio is higher in the pessimistic coronavirus case than in the optimistic scenario is “the longer duration would lead to a larger drop in spending on durables, which are highly tradeable,” said the WTO.

The WTO forecast assumes ratios will remain elevated in 2021. In its optimistic case, it projects merchandise trade will grow at 2.9 times the pace of GDP, by a rate of 21.3%. In its pessimistic case, it projects merchandise trade will grow at quadruple the pace of GDP, by a rate of 24%. In other words, ocean shipping volume might go up as quickly as it descended. Click for more FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller