A weekly look at what occurred in the oil markets of the U.S. and the world this past week and what’s ahead.

Markets in just the past few days have sent a strong signal that moving crude oil by rail may be past a point of no return.

When crude oil by rail began roughly 10 years ago, it was somewhat stunning. Moving crude oil by rail had faded from the industry years ago, though ironically, the control that John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil had over the rail shipment of petroleum in the late 19th and early 20th century was a major national issue.

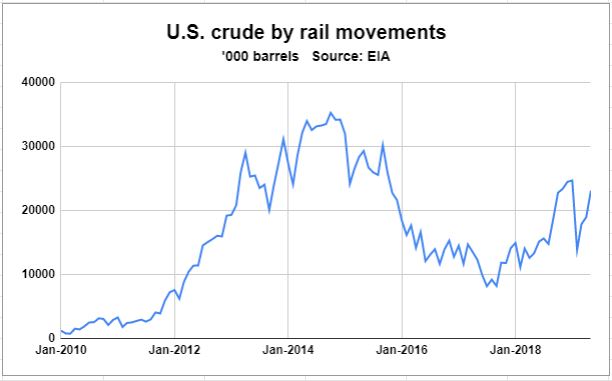

But pipelines, far cheaper and more efficient, displaced rail cars. Rail came back on the scene beginning around 2010 driven by several factors, all of them inter-related – U.S. oil production began to surge, particularly out of the Bakken oil fields in North Dakota, and oil couldn’t get out of the Bakken through the region’s limited pipeline capacity so rail terminals were quickly built. The parade of rail cars moved down to Cushing, Oklahoma – delivery point, and also where the CME crude contract began.

The economics worked because the oil sitting in North Dakota had limited options. Even though rail is far more expensive than moving oil on a pipeline, you can’t benefit from it if you can’t get any space on the line. As long as the wellhead cost in North Dakota, plus the cost of rail was less than price it could be sold at in Cushing – price that is on-screen at any given moment, since it is the price of the CME crude contract – the economics worked. And they did.

Some creative types then did a little more math and figured that you could take oil out of Cushing and send it via rail to the Gulf Coast. The Cushing price would be WTI-based, and it would be sold at a price tied to the world benchmark price of Brent. That WTI/Brent spread around its peak (or its nadir, depending upon your perspective) between 2011 and 2013 was well in excess of $20 per barrel and for a short time got as wide as $27.

This helped American consumers not one single bit. Because the U.S. imports and exports both gasoline and diesel, sales of those and other products are all consummated at levels tied somehow to world prices. That means that they all link back to Brent.

Refiners in the Midwest with access to crude at Cushing, depressed because of the glut there, could buy crude at WTI levels and sell products at Brent levels. For those companies, it was about as close to minting money as possible.

But bit-by-bit, the spread was chipped away. The reversal of the Seaway Pipeline in 2012 was an important initial step. Seaway had been set up to send crude from the Gulf Coast to Cushing. But the reversal allowed oil to start being drained directly by pipeline to the Gulf. That narrowed the Brent/WTI spread almost immediately.

You can see on the chart below a dip during that year in the amount of crude moved by rail, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA), right about the time Seaway reversed.

Crude-by-rail rebounded after that, as the Seaway reversal alone wasn’t enough to balance Brent and WTI, given the continuing surge in U.S. production. And while there was more pipeline capacity from Cushing to the Gulf, rail was needed to move Bakken crude oil to the East and West coasts.

Still, as the chart below shows, crude oil by rail movements peaked in late 2014 and have been trending downward ever since. But it’s still at a reasonably healthy level.

There is a change afoot that is more secular and does not appear to be part of the normal swing of markets. There is a flood of pipeline capacity coming online through the rest of this year and into 2020. The EIA has catalogued it in one downloadable spreadsheet.

There were developments just in the past few days. EPIC Midstream began shipping crude on a pipeline from the Permian Basin to the U.S. Gulf Coast. This comes hot on the heels of another new Permian-Gulf pipeline launched by Plains All American called Cactus II.

Next year, some big pipelines are going to open up. The Wink-to-Webster pipeline serving the Permian is going to open at a whopping 1 million barrels per day (b/d), an enormous size. The Seahorse line is to take 800,000 b/d, also a big line, from Cushing to Louisiana. And as the EIA database shows, those aren’t the only ones.

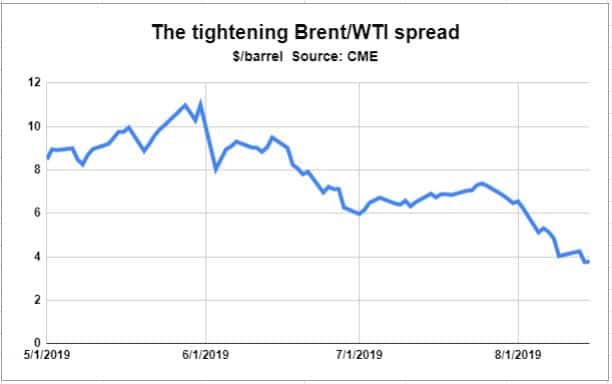

Even though these lines have been planned for some time, the market is starting to take notice. Between January 1 and June 30, the Brent/WTI spread averaged $8.69. From July 1 through August 16, it was $6.09. For August so far, it is $4.83. And for the last two days of trading, it was less than $4.00.

Firm data on the cost of moving crude oil by rail is somewhat less than transparent. A general consensus seems to be that a $10 difference exists between moving crude via rail rather than pipeline. It is clearly more complicated than that; if it was a simple $10, none would have moved earlier this year when the spread was at $8. But can any of it move at a spread less than $4?

The complexity also comes in the fact that most crude by rail doesn’t go from the Permian or Bakken to the Gulf Coast. The biggest movements are from PADD 2, which includes the Bakken and Cushing, moving crude to the East Coast – 4.6 million barrels in May – or to the West Coast, 6.3 million barrels that month, according to EIA data.

Still, the crude oil that could otherwise service those areas, all of it imported by ship, is generally priced on Brent or some derivative of Brent. That means that the Brent/WTI spread still matters to those markets as well, even though there are no pipelines in those areas, existing or planned. But that doesn’t mean the new pipelines don’t matter to those areas. The new projects in the mid-continent are narrowing the Brent/WTI spread and that should have some impact on regions that are not on the Midwest/Gulf Coast pipeline grid.

But it’s clear that crude-by-rail out of the Permian to the Gulf Coast is a dying business due to pipeline growth. You might not know it to look at the data. In May, the EIA recorded 2.1 million barrels of crude by rail that stayed within the regional area known as PADD 3, which includes both the Permian and the Gulf Coast. That would be overwhelmingly moving Permian barrels to the Gulf Coast. The record amount was in April 2013, when it reached 4.2 million barrels. But a year ago, that figure was 191,000 barrels.

Don’t let that surge fool you. The steel going into the ground is going to all but put an end to this traffic and the Brent/WTI spread will enforce it by making rail movement mostly uneconomical within the Permian-Gulf corridor. As the PFL Railcar Report recently noted, “Crude by rail in the Permian is all but over for the near-term as new U.S. pipelines are poised to start a price war for shale shippers.”