A fascinating Morningstar/Pitchbook note on Uber analyzing its prospects for an IPO next year recently came across our desk. “Uber May Pick Up Investors, Along with Riders, in its IPO,” dated July 19 and written by Morningstar equity analysts Ali Mogharabi and Julie Bhusal Sharma, as well as Pitchbook’s emerging tech analyst Asad Hussain, acknowledged that Uber had a relatively narrow moat, with its customers able to switch to strong competitors in Lyft and Didi with a simple download. But Mogharabi et al wrote that Uber should be able to exploit its network effect and vast telematics data to restore faster growth rates.

The sections of the note regarding Uber Freight were less obvious to us, and revealed some naïveté on the authors’ part about freight brokerage in the United States. Let’s start with the numbers: Morningstar estimates that in American freight brokerage, Uber Freight has a $15-20B addressable market expected to increase at a 9% compound annualized growth rate through 2022 to $27B. Morningstar admits that while Uber Freight will see fierce competition from incumbents like C.H. Robinson, its model still calls for Uber Freight to grow its gross revenues by 20% annually through 2027. In other words, Morningstar thinks that Uber Freight’s revenues will grow at more than double the rate of the overall market, meaning that Uber Freight would be capturing market share at a significant clip.

There are some advantages that Uber’s technology and ease of use give to shippers and carriers. Yone Dewberry, Chief Supply Chain Officer at Land O’Lakes, said at the 3PL and Supply Chain Summit in Atlanta that the company was undergoing a pilot with Uber Freight to find capacity because “traditional brokerage is too slow,” but noted that “we don’t know if it will work.”

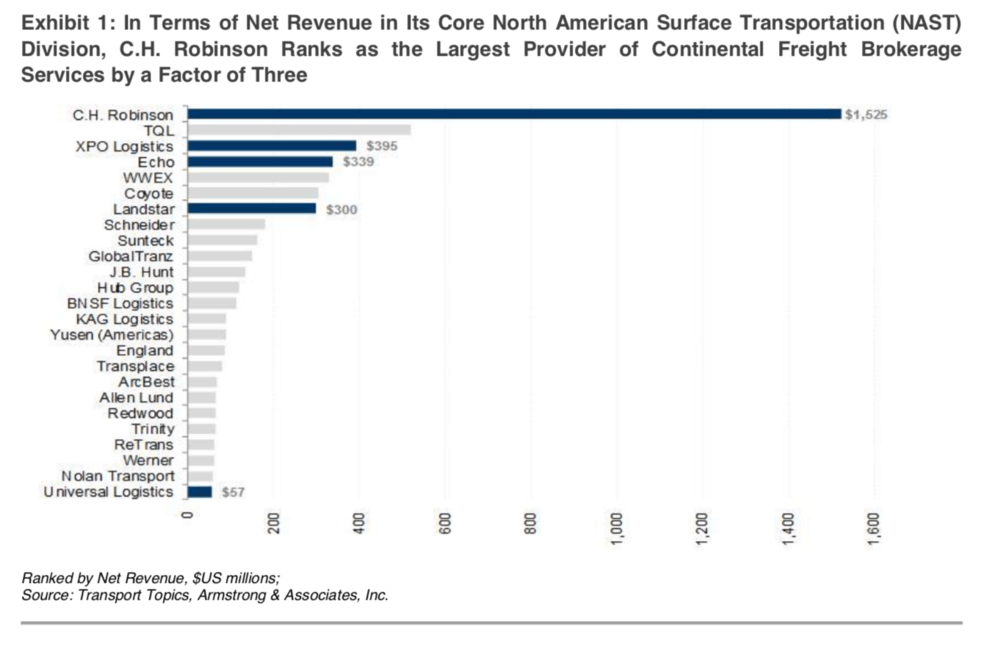

But there are also significant headwinds to Uber Freight’s rapid growth in revenue and market share. Firstly, in a list of the top 25 North American freight brokerages by net revenue, Uber Freight does not even make the list. C.H. Robinson dominates the freight brokerage industry, bigger than its nearest competitor by a factor of three. Even the last generation of tech-powered disruptors, companies like Echo, Coyote, and Redwood, do not represent threats to dislodge C.H.’s massive network, dense with both freight and capacity.

Secondly, some of the oldest incumbents in the freight brokerage space—namely C.H. Robinson and J.B. Hunt—have some of the best technology. Stifel’s Bruce Chan wrote about C.H.’s technology in a note dated June 18: “Significant investments in technology — with its proprietary Navisphere platform sitting at the top over the past five years mean increasingly automated processes, helping to drive down margin, keep pricing competitive, and to offer customers unmatched features and service.” Meanwhile, FreightWaves wrote in April that while the vast majority of carriers’ loads are still directly sourced from shippers (upwards of 80%), with load boards and brokers accounting for the rest, digital apps are barely a blip on the radar. Less than 1% of carriers’ loads were sourced through apps, according to our survey data, and among those apps, which one is the most popular? As far as we can tell, it’s JB Hunt’s 360 app, which handled $90M of freight in the first quarter of 2018.

Finally, as users of Uber’s regular ride-sharing service know, the app has very limited intelligence into what the customer needs and the way the car is equipped. Uber can’t match a parent and young child with a ride that has a carseat, and it can’t find a car with a lift for a user who’s wheelchair-bound. Similar limitations have hamstrung Uber Freight to this point: the app really only knows a few things—the location of a truck, the origin/destination of a particular load, and the basic characteristics of the truck. It doesn’t know the truck’s route, where the driver wants to go, or the driver’s remaining hours of service.

“Uber Freight is actually fairly rudimentary. There is not a lot of intelligence beyond a truck’s location and the characteristics of the vehicle,” said Kevin Haugh, Chief Strategy and Product Officer at Omnitracs, told Forbes in April.

The last question lingering over Uber Freight’s upside is how it will adapt to cyclical shifts in the freight market. In a period of tight capacity and high demand, like the one we’re experiencing now, the spot market is well-populated, active, and volatile, making apps like Uber Freight relatively attractive. But in a downturn with depressed freight demand, there’s far less reason for shippers to go to the spot market to move their freight, and if you’re a truck driver on the spot market using an app to source your loads, they’re going to tend to be much less lucrative.

In sum, while freight brokerage in North America is a large and still quite fragmented business, we think that the weaknesses of Uber Freight’s technology, the significant network effects already exploited by the largest incumbents, and the as-yet extremely limited market penetration of digital apps all place strong barriers to what Uber Freight wants to achieve.

Stay up-to-date with the latest commentary and insights on FreightTech and the impact to the markets by subscribing.