The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of FreightWaves or its affiliates.

There is a great deal of passion about coal as a railroad commodity

Some suggest that the railroads have been in denial about coal’s decline as a business sector. Yet, I bore witness to an awareness of the risks of the coal decline a long time ago.

Coal’s declining role was seen by two railroads about 25 years ago. It was a footnoted statistical analysis that only a few strategic rail planners saw as prudent due diligence.

Who probed the outlook regarding coal’s role in the energy mix? Among the participants were railroaders David LeVan and Al Braverman.

Strategic planner Jim McClellan confided that he also probed the changing landscape. Coal’s possible decline was a factor in Norfolk Southern’s (NS) market diversification strategy and the acquisition of Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail). Coal was a high-margin legacy business for NS. Conrail offered more general merchandise and intermodal balance.

While much of the strategic thinking almost three decades ago was beginning to be influenced by environmental issues, a few thinkers were concerned about the underlying economics of coal-fired electricity.

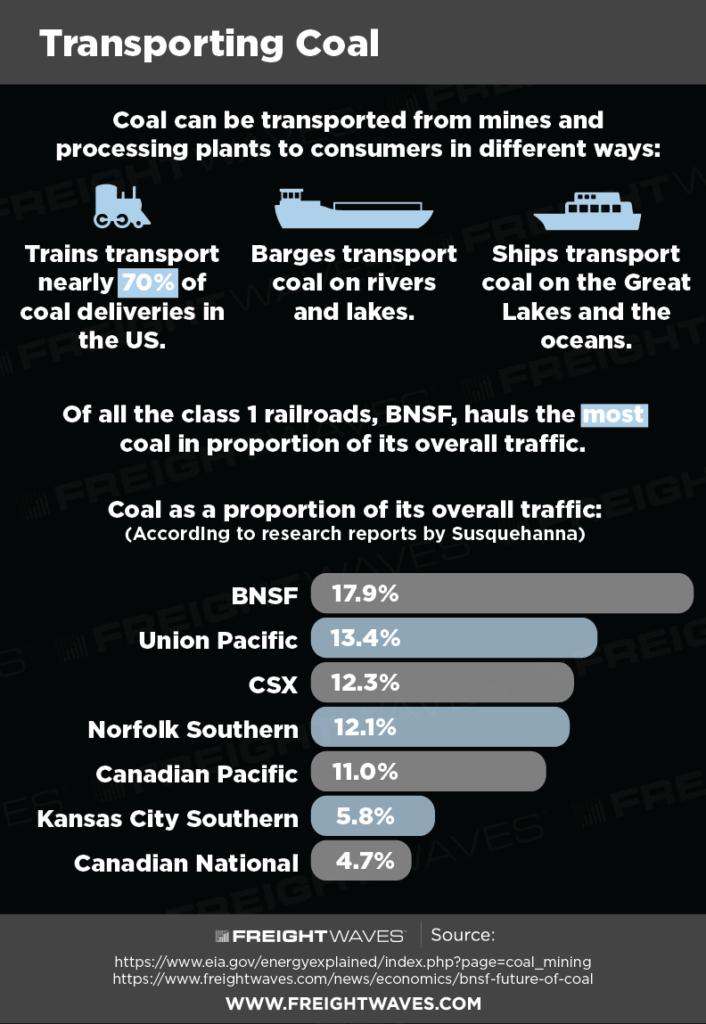

Why worry specifically about coal-fired power stations? Because about 90% of the coal hauled in the U.S. was for that purpose.

Metallurgical quality coal used for the steel industry was often the highest profit margin coal for railroads. But the volume of metallurgical coal wasn’t as large as “thermal” coal used to generate electricity.

Why the intellectual challenge to coal’s future so long ago?

After all, coal hauled by rail continued to increase in volume for quite some time. The amount of Powder River coal hauled out of Wyoming and Montana continued to grow for another 15 years after the initial challenges were quietly discussed.

What is the inferential thought process?

The thinking that brought on the strategic 1992-94 questions came from a contrarian look at future markets.

Some call it “inferential thinking.” It is not often practiced by companies.

The essence is to challenge how political, economic or business forces are beginning to signal changes even if things look normal. The changes are often so small that they only appear as footnotes on the back pages of technical journals and in the business sections of newspapers.

Remember that 1992-94 was when printed media was the institutional way that news was circulated.

At Conrail, the process of using inferential thinking and remote data points to assess the future was advanced by an outsider – Andre W. Alkiewicz. He and his colleagues offered contrary thinking about future trends through their small company, Perception International.

There was a lot of resistance. After all, departmental and business unit empires were threatened by such thinking. The database supporting inferred conclusions was not as robust as those supporting traditional thinking.

To be inferential, one had to be open to unconventional thoughts and outcomes.

Others often “resisted” this quirky type of imagining unusual outcomes, in part because they couldn’t intellectually adapt to a different market-based future. At least not easily.

However, note that within two years of the inferential thinking regarding coal, Conrail was sold in two parts to NS and CSX.

So what evidence was available prior to say 2000?

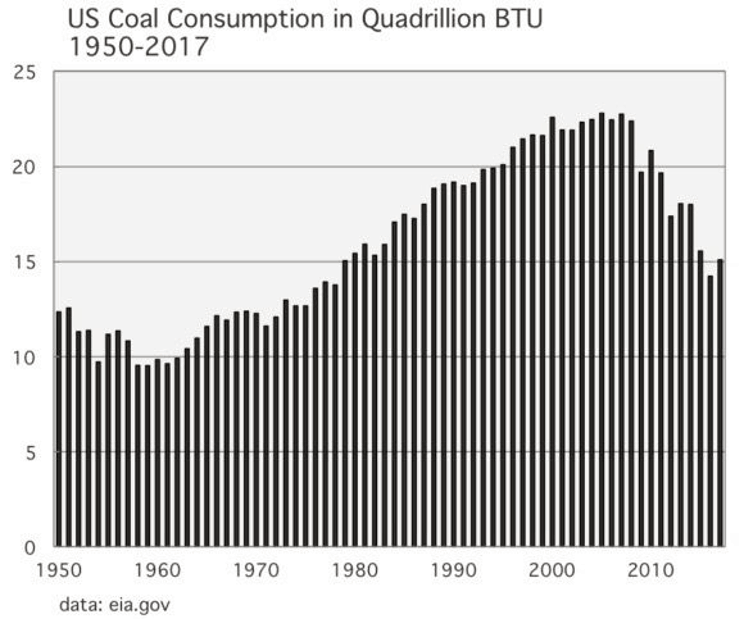

Figure 1

Changes in electric power generation have rippled through the coal and rail industries

It was easy to ignore the change in the slope of growth 1988-1995 period

If we look closely at Figure 1, we can see a small change in the slope of actual coal traffic growth. It occurred roughly between 1988 and 1995. It wasn’t very big. It was later offset by a rapid upslope pattern into 2006. The temporary slowing could easily be dismissed since the rate of growth then increased.

But for a long-life asset sector like railroading (ties can last 35 to 50+ years; rails can last even longer; and some bridges and track embankments “forever”), the return to higher growth from areas like the Powder River Basin seemed “reassuring.” Why worry?

In big organizations, the majority of the managers in charge “cling to status quo assumptions.” Their fallback position is often “even in a worsening case, we can milk the assets in place.” Why worry?

Inferential thinking is too speculative. Let’s carry on with the status quo.

Jumping ahead in time, prior to about 2010, several things were occurring. Little of this was front page news.

In 2000, more than half of the country’s electric power was generated by coal. Why worry in 2000? After all, new coal-fired plants were on the drawing board, and coal was usually the cheapest source of energy when converted to price per kilowatt hour of domestic electricity.

But across the United States, electric power companies began to slowly move away from coal. Who foresaw that coal-fired electricity would drop from about 52% in 2000 towards less than 25% by 2020?

Back in 1992, few foresaw the extreme drop in eastern U.S. Appalachian coal mining. And it is likely that almost nobody forecast a competitive threat from natural gas. Not in 1994.

Few energy sector experts saw the fracking revolution even as late as 2007. Now, about 37% of the nation’s electricity is natural gas-sourced.

How and why is interesting. Perhaps as much as 25% of the nation’s natural gas is an off-shoot from crude oil production. That’s created a huge natural gas supply – far greater than the nation’s natural gas market demand.

The result? A huge discount in the price of natural gas. Who saw that outcome early on? Early on means before it was front page news.

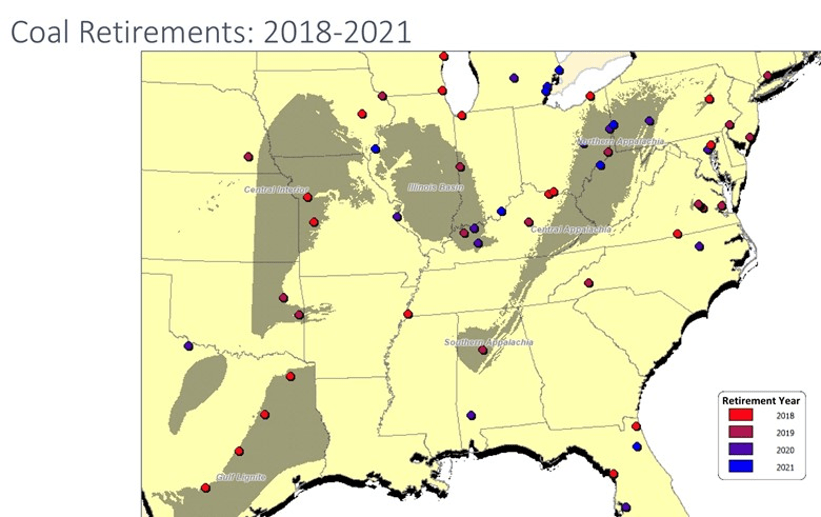

For the railroads, the impact is that customers are shifting away from coal-fired, rail-supplied power stations. Between 2010-2019, some estimate that more than 500 coal-fired power stations were closed or announced as closing soon. Most were or are supplied with coal by rail.

How much power is that? It is in the range of 100 gigawatts of electric generating power that was at one time powered by coal that was delivered by railroads.

Can rail-hauled coal recover those market location losses? Probably not.

One reason is that once a power station converts its boilers to natural gas (or even to oil) it is too expensive to redesign and or replace those modernized units – not without a subsidy or a radical and unexpected coal technology breakthrough.

Figure 3

Conclusions early in 2020

Looking towards 2030, here are a few inferential conclusions.

The volume of coal hauled by rail is unlikely to return to pre-2010 levels. No one is predicting that – are they?

This has a continuing impact upon the railroad car fleet and its replacement rate. The seven Class 1 railroads have managed to survive the coal losses – and even improve their financial results. How? Mostly they accomplished this by rationalizing their physical assets of yards and tracks, storing locomotives and rail coal hopper and gondola cars, and cutting the size of their workforces.

The decline in coal has created a parking lot of used coal gondolas and coal open hopper cars that are in good condition. These excess railcars are a potential bargain for international coal shippers that could use the railcars on foreign standard gauge railroads.

For a little over the scrap price, plus shipping charges, a foreign railway can buy railcars with perhaps 25 years remaining life. That’s a great deal, since new cars cost over $100,000 each.

In the wake of coal’s decline (and other structural changes), the railroads reduced their fixed asset base (balance sheet assets) and lowered their variable costs of crews, fuel and overhead. But can they continue cost cutting indefinitely? There will be practical limits. And the railroad supply industry will be impacted. What is their strategic plan?

On the upside, we can inferentially conclude that the coal movements are not vanishing. There is still a great deal of coal moved by rail.

What is your inferential thinking telling you about coal and railroading’s future?