The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of FreightWaves or its affiliates.

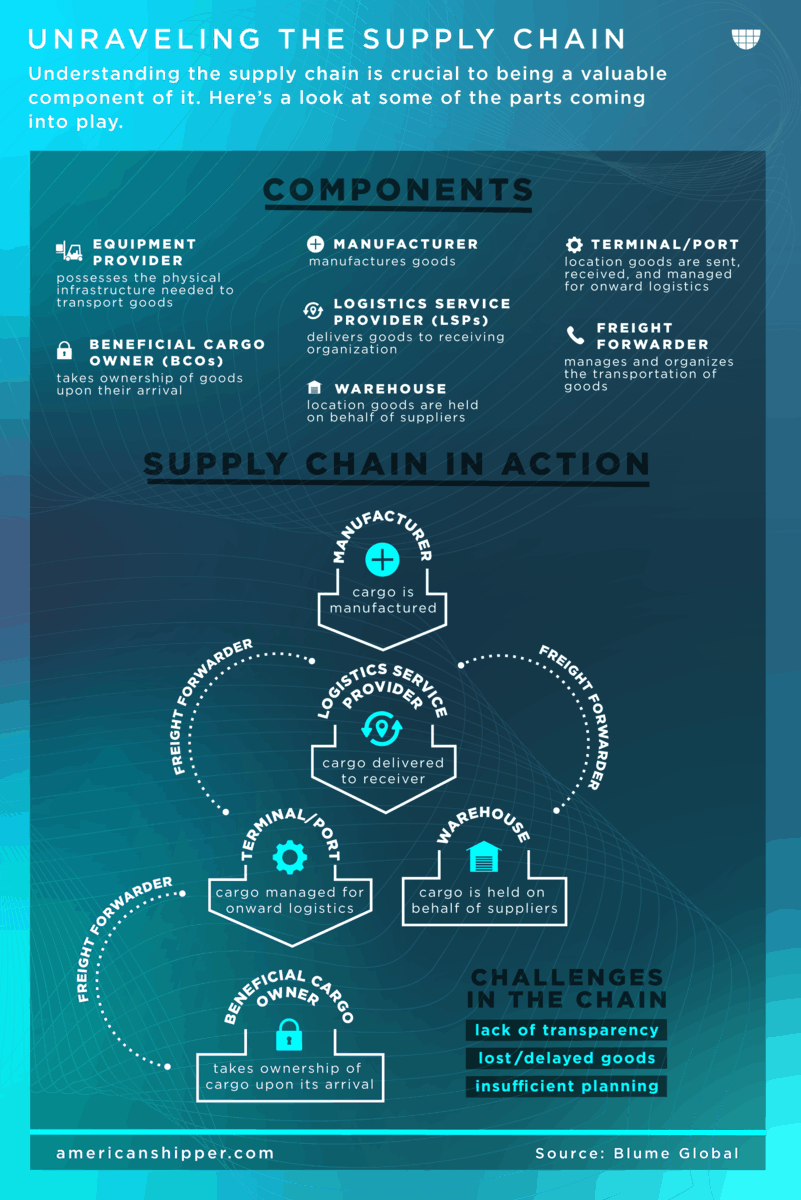

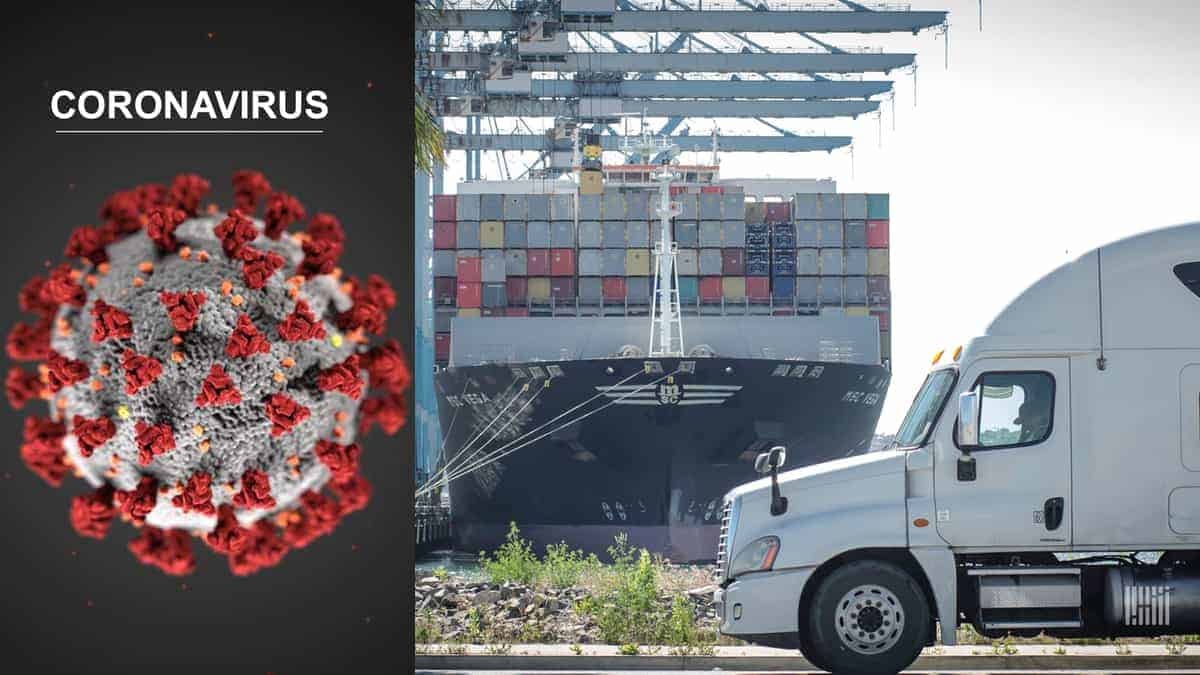

Since the coronavirus pandemic took hold earlier in 2020, supply chain has become a household word. Investors, like the public, have woken up to the fact that supply chains are the engine driving economic prosperity.

Almost perversely, supply chain is also the final frontier of tech-based efficiency optimization. Insiders joke (quite fairly, as it turns out) about billion-dollar procurement-management-disposition cycles that are managed in spreadsheets. Some larger organizations try to use ERP systems, which are often ill-suited to supply chain workflows, while a fortunate few enterprises host game-changing custom control tower systems. Supply chain, it seems, is ripe for disruption.

But investors, however keen they are to jump on an opportunity, know a rabbit hole when they see one. To provide some help with navigating the complexities of supply chain investing, I spoke with three tech experts with different perspectives: Dave Anderson of Supply Chain Ventures, the godfather of supply chain investing; Brian Aoaeh of REFASHIOND Ventures, the next-gen supply chain specialist; and Ryan Floyd of Sandhill Road’s Storm Ventures, the supply chain investment skeptic.

(Photo: Jim Allen/FreightWaves)

Why supply chain – and why now

Anderson, who easily has the most extensive background in supply chain and supply chain investments, takes the recent uptick in buzz about supply chain in stride. “Everyone’s figured out that supply chains are important, given COVID-19. They may not know much about what they are, but they’ve understood that we’re about seven days away from starvation without them,” he observed.

He describes supply chain investment as being “white hot” in the past five years, citing valuations like Flexport, which became a unicorn with a $1 billion investment from Softbank. “Prior to that, there wasn’t as much going on, but recently at Supply Chain Ventures we’ve looked at around 300 startups a year.”

Floyd, whose firm is focused on a wider range of business-to-business/enterprise SaaS, is open to supply chain opportunities but is also more cautious. “We haven’t seen as many opportunities for investment in operations as I would like, but it’s going to be a bright area for investment going forward. You can start with things like logistics, and see how much things have changed in just the past five years. A lot of that has to do with the success of companies like Amazon putting a tremendous amount of pressure on everybody else. That’s good, because now everybody needs to up their game in terms of what their capabilities are. Think of something like handling returns, and accurately predicting delivery times. The problem with trying to do things like that before, using people, was that it was hard to scale because your costs would go up. Now, with technology, it’s a lot easier to offer an experience comparable to what Amazon is offering.”

Aoaeh finds Floyd’s skepticism understandable. He agrees that 10 years ago, it would have been difficult to do things that we see innovators doing now, because technologies weren’t as advanced.

“If you talk to some investors who have a background in supply chain,” said Aoaeh, “they will tell you a lot of horror stories about technologies that they thought would be groundbreaking many years ago but weren’t. At that time, the potential was there but the technology wasn’t mature enough. So the massive companies that had the balance sheet to invest in that sort of thing could do it, but for everyone else it wasn’t realistic. If you invested in technology at that time, you probably lost your shirt, but that has all changed with cloud computing, edge computing, mobile devices, etc.”

Floyd also noted that the prospects for software investments as a whole have improved. “I remember a time when investors pooh-poohed software entirely, because of the IBM/Microsoft history, and people didn’t see the ability to make money on applications at scale. It’s amazing to see how that has completely changed. No one ever asks about the hardware anymore.”

(Photo: Lexi Alvidrez/FreightWaves)

Potential impact

For organizations, the benefit of choosing the right technology lies in tapping into cost-saving efficiencies.

“Costs related to supply chain will account for 30% to 80% of sales,” explained Aoaeh. “Restaurants are at the low end at around 30%, and energy is at the high end at 79%. Therefore, any innovations that can help you get around these costs will be really, really big.”

He continued, “For any company that wants to improve its profit margins, there are two strategies they can take: a marketing-driven approach to increase demand; or a supply chain-focused approach to drive down costs. Driving down supply chain costs is always a strategy that will win. This is because your sales and marketing efforts will always run into a market that will inevitably dictate the price. On the other hand, you have more control over internal costs, so that becomes easier to tune.”

There’s another problem with spending money to increase demand, Aoaeh said. “Ultimately, you’re going to have to invest in capital expenditures to satisfy that additional demand. You’re going to need to buy more machinery, etc., and so you have costs going up.”

So if tuning the supply chain can yield such ROI, why hasn’t this already been happening? It has, but Anderson explained that the current tools aren’t up to the task yet. “The reason that a lot of supply chains get into trouble is that they rely on old data – think three-month old data in SAP, Oracle or I2/Manugistics [now both JDA/Blue Yonder] – that’s used to plan and execute supply chain decision-making.”

The clock is ticking on the status quo, however, especially now that COVID-19 has shown the consequences of a lack of resiliency.

“It can’t be that way in the future,” Anderson said. “We now have all kinds of real-time data on traffic, weather, product reviews, comments on Twitter, shipment visibility data, declared data from loyalty programs, etc. There’s a huge amount of information that, frankly, all of the legacy supply chain decision-making systems can’t use. That’s why we’re investing in artificial intelligence [AI] and machine learning [ML] tools that sit on top of these legacy systems and feed back into the legacy systems via an API. No one’s saying we’re going to replace them any time soon, so the CFO can continue to get his financial and inventory data, but we can better manage execution decisions in transportation or a planning decision around inventory positioning using AI/ML and real-time data.”

Beyond the potential wins for organizations, there are further horizons to watch for in terms of data. “One of the things in supply chain that I think will be really interesting,” Floyd said, “is that a lot of the data that exists in a supply chain gets tracked elsewhere. It’s just been hard to find commonality in the data to have intelligence about what’s really going on in the supply chain. A better comprehensive understanding of the data from origin to final destination can give you great insight. Leveraging data that you already have to get intelligence and insights about your supply chain is a great story, because you can do this without introducing additional friction into the system.”

Aoaeh also pointed out that, on a macro level, the potential opportunity waiting in supply chain optimization is huge. “There is nothing that we do in the world that doesn’t depend on a supply chain, and if we can increase efficiency and cut costs by even a small percentage, it can be a really, really big deal. If you think of the world as a $90 trillion GDP entity, then even a 1% efficiency is a big opportunity.”

(Photo: Jim Allen/FreightWaves)

Challenges in supply chain investment

Floyd says that one of the big problems with supply chain investment is that even the term itself can be unclear. “Supply chain means different things to different people in different industries, and that’s what makes investing in supply chain a bit difficult to grab hold of. It’s not like, say, Microsoft Office, which has the same functionality no matter who uses it in any industry. Another thing is that the integration on the supply chain side tends to have a lot more touch points in a lot of other systems, and often physical systems. When thinking through an investment, we need to know the cost to deploy to the customer, the cost to support the customer, and if there is upsell potential against that opportunity. Another challenge is that you have to target the companies that have large enough supply chains to really go after. You can’t build a business on serving one client.”

Aoaeh said that, for investors, the opportunities in supply chain are very difficult to realize if you don’t have a supply chain background. “Many venture capitalists have finance and consulting backgrounds and haven’t spent time in supply chain. I don’t have that dyed-in-the-wool supply chain background either, but the difference between me and some other folks is that I like to spend time digging into things, and I spent a significant portion of my professional experience prior to investments in operations, or the back office.”

Further, Anderson is wary of tools that don’t offer a full view of a supply chain decision process. “In the procurement space, what I want to be able to assess is risk management. For example, what happens to supplier networks when there are earthquakes, floods or COVIDs, and what would you do about it?”

He and his business partner Dan Dershem have been looking at procurement from several angles. For example, the environmental, social and governance (ESG) perspective seeks to ensure traceability and compliance with regulatory standards governing, for example, conflict minerals and child or slave labor in the supply chain. It’s something they’ve been looking at for a while and that he indicated has begun to take off. “A company we’ve been working with has just landed Walmart, which wants to make sure that its 40,000 suppliers are following the guidelines.”

(Photo: Walmart)

The opportunity can also depend on what area of the asset lifecycle you’re looking at, according to Floyd. “Disposition is a little trickier,” he said. “The problem when you get to areas like disposition is that the value proposition often isn’t great enough to put technology in the mix. Sometimes it is – it depends on the assets you’re disposing of. If they have value, then sure, there is an opportunity there.”

Selling to enterprise in general is also getting harder, noted Floyd, because there’s so much competition right now for that enterprise mindset. “You really have to have a solution that solves a searing pain for that customer. No one’s going to deploy a supply chain technology because ‘gee whiz, that’s cool.’ But if the pitch is around, ‘we have to deploy this because it’s accurately going to predict what’s going to happen for our customers, because if we don’t they’re going to buy from another company’ – that will work.”

So what makes for a winning play in supply chain?

“You have to be a solution provider, not just a product provider,” Anderson explained. “When you see products, such as blockchain or IoT, looking for solutions, that’s when you really have to be careful.”

Floyd agreed. “We don’t invest in platforms per se. They’re great, and ultimately provide a lot of value over time. But if you think about it from a customer point of view, there’s no customer that goes out searching for a platform. Customers search for solutions to their problems – that’s why we’re maniacal about focusing on answering that question. If, once you’ve solved that, the answer is a platform, okay. Also, when we look at platforms, we look for something that goes beyond the application itself. You’ve got to have some kind of core infrastructure that allows you to build other products over time.”

(Photo: Shutterstock)

Anderson feels that it’s the details that will make the difference. “I look at a lot of this visibility stuff, and I think, ‘this is a product, but what is the real problem I am solving here?’ Do I care where that truckload of toilet paper is right now? Not really. Do I care where that multi-million dollar truckload of temperature- and shock-sensitive pharmaceutical products is? Absolutely – that’s the visibility I want. For the vast majority of supply chains, all I need is an approximation of location and status.”

He continued, “You want to solve problems in supply chain that no one else is tackling. For example, we’re working with a company, True Load Times, that focuses on detention times at logistics hubs. All kinds of parameters affect these wait times, and the question about how long a shipment will be waiting in a logistics hub or port is a huge black hole that exists in supply chain right now. This is because when you’re a carrier quoting a load, you’ve got to quote the shipment now with existing information, and if you’re wrong, you can’t go back and collect for that detention time. If you’re a carrier trying to best utilize their trucks and network, that’s huge.”

(Photo: Jim Allen/FreightWaves)

Has COVID-19 changed the investment landscape?

“Pre-COVID, the main investing spaces were virtual brokerages, e-commerce logistics, and I’ve also seen a lot of blockchain and robotics,” Anderson said. “That’s where a lot of the money had been deployed up until March 2020.

Floyd noted, “What’s been really interesting in B2B overall, is that we’ve seen a number of businesses that were doing well really accelerate.”

Anderson agreed. “Truthfully, we can’t see any major drastic changes beyond the trends that already existed. But the changes that, historically, would have taken 10+ years are now going to be accomplished in far less time. You’re going to see a lot of redesigning of businesses and supply chains as customer requirements change, with e-commerce being the poster child for all of that.”

Anderson also said that enough time has passed that the lessons we have from COVID-19 are pretty clear. “Supply chains are going to need to be more flexible and resilient in the face of unexpected change, and able to shift sourcing and distribution in days or weeks, instead of in months or years. And it’s not just COVID-19 – there are disruptions going on with China, and the possibility of companies moving elsewhere in Asia or to the U.S.

Floyd stated that the absence of major shifts is a good sign. “That bodes really well for continued investments in B2B and enterprise, whether it’s in supply chain, or newer areas like construction [which we’re looking at because there’s so much falloff for tech once you get out of the design phase], or manufacturing. We’re going to see a lot of venture investors put a lot of money there.”

(Image: Shutterstock)

Emerging trends

“If you look at operations right now,” Floyd said, “One of the things that’s interesting is that a lot of organizations have revenue operations people, or sales operations people, whose jobs are to make the whole system run more smoothly. And while that job may have been more physical before, now it involves things like stitching applications together and creating workflows between applications, ensuring that there are automatic triggers, making the onboarding of an employee a magical experience, and making the onboarding of a new customer delightful so they want to expand with your product.”

He continued, “The days of the ‘command and control’ CIO, who owns all the applications, are over – and have been for a while. But if you talk to a lot of CIOs, they never really wanted that job anyway. They don’t want to own some deployment, because they’re not the user who really gets the value. Now you’ll find that the top-level CIOs are more often in an enablement role. They’re thinking, ‘how do I help the different business units do more with technology?’. They’re focusing on bringing data that spans these units together in a more centralized way, and often security as well. Now, you’ll see in these divisions that there are tech folks that serve almost as mini-CIOs. People have realized how much leverage you can get out of technology when you’re really investing in it.”

When Aoaeh looks to the future of supply chain technology, he sees a lot of areas that are exciting, but cautions that some are further along than others.

“What we’re looking at in the next few years comes under four broad areas – next-generation logistics, advanced materials, advanced manufacturing and data and analytics,” he stated.

“We’re not going to be investing in companies that want to buy trucks, buses and ships, but we are going to be investing in startups that are creating software and possibly hardware that makes it possible to manage those assets, and manage them much more efficiently than was possible in the past.”

For Aoaeh, improving on sustainability will shape some of what is to come. “Advanced materials that allow us to divert goods that would have ended up in incinerators and landfills and turn them into new raw materials is important. Waste from plastics is a big issue for the circular economy, as is waste in fashion and apparel.”

(Photo: Alan Adler/FreightWaves)

Aoaeh pointed out that sustainability goes beyond the feel-good, to align with reducing costs for organizations. “Advanced manufacturing that enables us to create the things we need most frequently much closer to home, possibly 3D printing, will help reduce problems in a number of dimensions – waste, pollution and cost. It will also change the way we think about inventory management and could save on costs if it turns out there is simply no demand for what you’ve made.”

For the long-term, Anderson is looking at radical new sourcing strategies – essentially, more, not fewer, suppliers. He noted that while COVID-19 hasn’t created incredibly massive shifts, there will be some changes. “We’re seeing the death of just-in-time [JIT] as we know it – because much of JIT is single-supplier. There will be more in-country manufacturing and safety stock. To answer the need for better resiliency, we’re looking for technologies that help companies to really get deeper control over multi-tier supply chains.”

Anderson is also looking really hard at centralized supply chain planning. “Today there are too many people making daily decisions in things like forecasting, execution or transportation that violate so many of the rules because they think they know better. There are already some companies that are running on a ‘lights out’ basis, meaning they run the technology and live with the solution without significant and constant changes.”

He continued, “We’re also big on warehouse and process automation in the supply chain space, focused on reducing the number of human, paper and software interactions to complete tasks. For example, the classic freight transaction has 18 steps from RFQ to final payment, and so many of them are not automated. We’re also looking at tools that enable the ability to pivot, and building more flexibility into supply chains – the best guys doing local delivery operations are continuously re-optimizing throughout the day.”

Improvements in internet and security technologies will also play out in interesting ways, Anderson said. “We’re not fully sure what 5G is going to mean yet, but it’s going to allow inexpensive access to a huge amount of IoT and machine learning data. There are also new security technologies for premium consumer goods brands like Arc’teryx and Canada Goose that can be built right into the product. For these brands, solving the problems of counterfeiting will mean reclaiming huge chunks of sales – 25% to 30% in a lot of cases.”

(Photo: Eric Bakker/Port of Rotterdam)

Excellent potential

For all three investors, supply chain technologies will continue to show promise; indeed, two have already used it to build successful careers.

Aoaeh and Anderson have both reported that they spend significantly more time fielding questions about supply chain from generalist investors in both venture capital and private equity firms.

Anderson advised, “If you don’t have the knowledge in the space, you have to find someone that you can bring in that understands supply chain. Maybe turn to an associate in your firm who came out of supply chain, and has been through the wars. There are a lot of those people now who are younger and get how things like AI and ML and real-time data can improve supply chain decision-making.”

Even for Floyd, the outlook is promising. “Some people see venture capitalists as not wanting to go out on a limb, but when you look at what people invest in today versus 20 years ago it’s really pretty amazing. Who’d have thought you’d be funding supersonic jets, or self-driving freighters or rockets. If you combine that with everything that’s happening in digital, the future looks pretty bright for tech across the board.”

More about our experts

Logistics visionary Dave Anderson has been a leader in data-based supply chain optimization since the 1970s and worked as an operations and technology consultant throughout the 1990s. A former managing partner at Accenture, he was a founder of its multi-billion dollar supply chain consulting practice. Today, Anderson and business partner Dan Dershem lead Supply Chain Ventures LLC, an early-stage and late-stage venture capital fund focusing on AI/ML-enabled supply chain software. A few of their successful investments and exits include Descartes (TSX: DSG) (Nasdaq: DSGX), Llamasoft, Shipmonk, Loadsmart, SupplyAI, Transporeon, LeanLogistics (acquired by Brambles), Control Group (acquired by Google/Intersection), Kiva Systems (acquired by Amazon), SilverPop (acquired by IBM), Optiant’s Power Chain Solutions (acquired by Logility), Steelwedge (acquired by E2Open) and Macropoint (acquired by Descartes).

Brian Aoaeh is a venture capitalist (currently a cofounder and general partner at REFASHIOND), educator, columnist and co-founder of the New York Supply Chain Meetup and The Worldwide Supply Chain Federation. He has been a professional investor since 2008, and spent eight of those years building an early-stage venture capital firm, KEC Ventures, from scratch. Jeff Citron, founder of KEC Ventures is known for stock trading platform Island ECN, Vonage and for Datek Online. The firm grew to $98 million in assets distributed across two funds and 51 investments, managed by a team of nine people. Today he is frequently consulted by other investors about supply chain-related initiatives as he and his co-founders build REFASHIOND.

Ryan Floyd is Co-Founding Managing Director of Storm Ventures, an early-stage investment firm that was the first on Sandhill Road to focus on B2B/enterprise SaaS. Since its inception in 2000, Storm has grown to encompass over 175 investments in tools for marketing, engineering, security, IT, HR and targeted apps for a number of verticals. Some of Storm’s most successful exits include AireSpace and MetaCloud (both now owned by Cisco), Berkana (now owned by Qualcomm), EchoSign (now part of Adobe Acrobat), RedLock (now owned by Palo Alto Networks) and Marketo. Currently Storm is specializing in go-to-market, and is starting its sixth fund.