It should come as no surprise: Just as you’re paying a lot more for gasoline at the pump, ship operators are paying a lot more for marine fuel. In fact, average marine fuel prices are rising even faster than landside fuel prices. They’re now just a few dollars shy of all-time highs, with a new record seemingly imminent.

That’s bad news for shipowners, and to the extent fuel cost is passed on, bad news for cargo shippers, and, ultimately, those who buy imported goods.

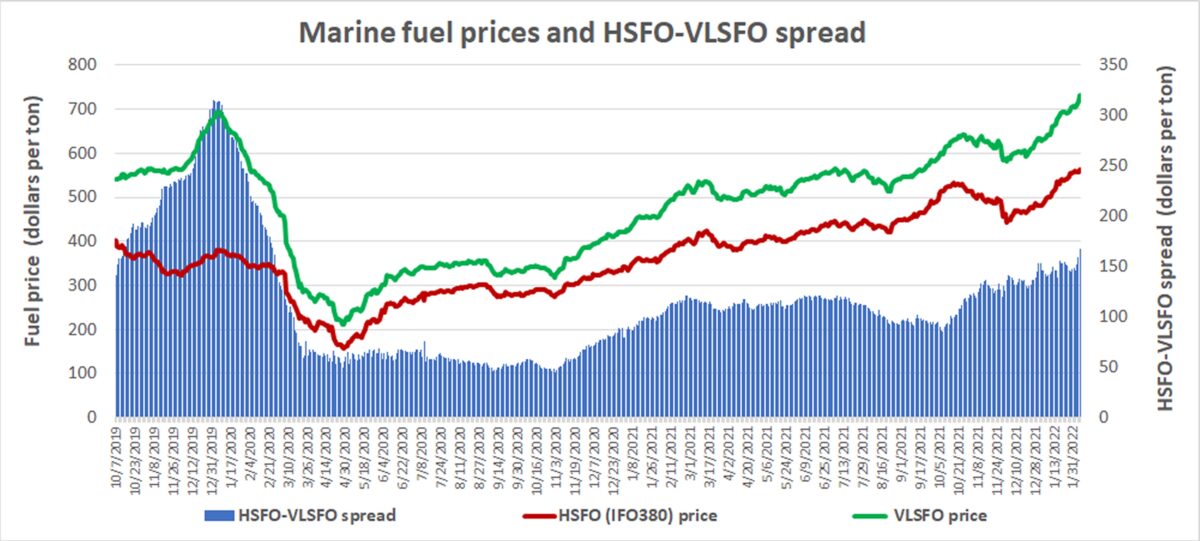

The majority of cargo ships burn 0.5% sulfur fuel known as very low sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO). As of Friday, Ship & Bunker estimated that the average VLSFO price at the top 20 bunker ports had risen to $731.50 per ton, up 55% year on year. The national average gasoline price rose 40% over the same period, according to AAA.

IMO 2020 transition price beaten

There have been three periods when marine fuel pricing has been near today’s levels.

The most recent was in January 2020 in the immediate aftermath of the IMO 2020 environmental regulation. IMO 2020 required all ships not equipped with exhaust gas scrubbers to burn costlier VLSFO. Those with scrubbers could continue to burn the cheaper, traditional 3.5% sulfur fuel known as high sulfur fuel oil (HSFO).

During the initial changeover period, Ship & Bunker’s daily average price (for the top 20 ports) of newly introduced VLSFO peaked at $694 per ton on Jan. 6, 2020. That high was surpassed two weeks ago, on Jan. 27.

Just shy of March 2012 high

Prior to 2020, the majority of modern commercial ships burned HSFO. There were two periods when the historical HSFO price was near current VLSFO pricing: in 2011-2012 when crude pricing was consistently over $100 per barrel, and in 2008 when crude pricing briefly spiked to $140 per barrel (marine fuel pricing mirrors crude pricing).

Ship & Bunker data goes back to 2012. It shows that HSFO (IFO 380) had a slightly higher price than current levels in March 2012, at $746 per ton for the top 20 bunker ports.

“Right now, it is certainly getting close to an all-time high, but not quite,” Ship & Bunker Managing Director Martyn Lasek told American Shipper on Monday.

Just shy of 2008 July high

According to Lasek, “The 2008 spike was relatively short-lived versus the 2011-13 period, which would have led to bunkers being more closely matched with crude prices in the 2011-13 period than in 2008. With a sudden spike and drop [in crude prices], bunkers don’t have a chance to fully catch up with crude before it falls again. But sustained highs get everyone on the same page with pricing, globally speaking.”

To the extent HSFO pricing in 2008 did exceed current VLSFO levels, it appears to have been for only a very brief period and by only a few dollars more.

A July 11, 2008, report from Platts put IFO 380 pricing in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, at $724 per ton; Fujairah, United Arab Emirates, at $738; Houston $742; and Singapore $753. Current VLSFO prices are now within $40 per ton of reported 2008 HSFO highs in those four leading bunker ports.

What it means to cargo shippers

In an online post, Lars Jensen, CEO of consultancy Vespucci Maritime, addressed the consequences of surging marine fuel costs.

Jensen pointed out that back in 2012, high bunker costs “triggered a wave of emergency fuel surcharges as well as a further step into super-slow-steaming by ocean carriers.” (Slow steaming refers to carriers intentionally reducing speed to cut fuel bills.)

In 2022, said Jensen, “high [fuel] prices have to be seen in the context of the supply chain bottlenecks. Slow steaming to mitigate the impact from high fuel prices only makes financial sense if you have excess capacity, which was the case in 2012. If you do not have overcapacity, it is more sensible to increase freight rates instead and maximize asset utilization, which is the case right now.”

The only solace for cargo shippers and consumers: Fuel costs, albeit historically high, are just a drop in the bucket compared to overall freight costs. Jensen foresees “continued upward pressure due to bunker surcharge adjustments, although these are quite small relative to the current extreme spot-rate environment.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller