Whenever the trucking market slows, truck drivers look for someone to blame. Normally, a slowdown is just a function of supply and demand. The market has too much dispatchable capacity compared to the total number of loads on any given day.

This summer, the trucking market could have one of its steepest declines in recent years and there is an entity that deserves much of the blame – the Chinese Communist Party and its draconian and inhumane lockdowns.

While the motivations of the Chinese government are unclear, one thing is certain – anyone subjected to a Chinese state lockdown compares it to being imprisoned in their own homes. As seen in several widely shared media posts, the Chinese government has started to erect metal barricades to block people from leaving their homes, preventing passage even for food or medicine.

While Americans watch in horror as innocent Chinese citizens are caught up in an ill-conceived, reckless, or nefarious – take your pick – act by the Chinese Communist Party, there is little Americans can do about it. But like most geopolitical events these days, the lockdowns in Shanghai and other Chinese cities are also a supply chain story that will have a dramatic effect on domestic freight markets.

The recent slowdown in U.S. truckload markets is likely a precursor to a steeper decline in the coming weeks. The lockdowns in China were not a factor in slowing U.S. truckload volumes in February and March, as evidenced by record container imports at nearly all major U.S. ports.

But that shouldn’t give anyone comfort because the slowdown is about to hit U.S. ports – and the trucking companies that service them – in a dramatic way. FreightWaves estimates that container imports from China represent approximately 16% of U.S. truckload volumes and an even larger percentage of U.S. dry van truckloads. After all, nearly half of the containers that come into the United States originate in China.

The lockdowns in Shanghai began on April 2 and the lockdowns in Guangzhou began on April 11. As geopolitical analyst Peter Zeihan described the situation on Twitter:

Beijing, which is the political capital of China, was expected to be spared the lockdowns by many analysts. This appears to be wishful thinking and Twitter lit up on April 24 with reports of Chinese state police starting to implement similar measures to those seen in the preparation for lockdowns in other cities.

The three largest cities in China are going to be removed from the world market. According to analysts, at least 40% of China’s GDP has been taken offline and this was before lockdowns began in Beijing. The vast majority of this GDP is directly related to global manufacturing. Removing it means removing the flow of containers from the world economy.

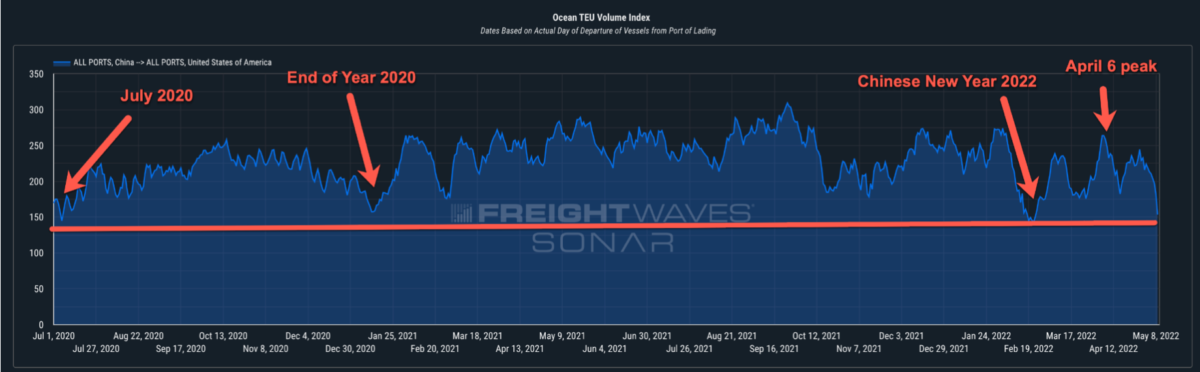

Container volumes from China to the United States started to fall on April 6. It hasn’t been a direct line down; more like a roller coaster. In the first 10 days, container volumes dropped by 31%. Volumes have since rebounded about halfway, to “just” a 16% drop. But according to FreightWaves SONAR’s volume booking forecast, volumes have started to drop once again and could fall to 50% of the April 6 number by May 9. This would be nearly the same level of a drop that China to U.S. exports saw during the Chinese New Year in 2022 and lower than any other point since July 2020.

Chinese ports are operating, but the bigger risk is with Chinese trucking operations. According to a report in Bloomberg, only 20% of Shanghai’s trucking capacity is operating. Trucking is a bigger part of the flow of containers in and out of the Chinese ports than in the United States. Over 75% of container volumes in China ports enter or exit on a truck, while in the U.S. both trucks and railroads move freight from our ports.

The loss of trucking capacity in China means that raw materials and components can’t get from the ports to factories and finished goods can’t leave the factories to the ports to be put on ships for export. The temporary blip (dead cat bounce) was likely containers that were already in the queue at the port prior to the lockdowns.

Since factories can’t receive new components or raw materials, they will also stop operating once their supplies are exhausted. Supply chains involve large webs of suppliers that are interconnected and just because one supplier is online does not mean that other suppliers are. Once they shut down, it will take much longer to bring them up to full productivity.

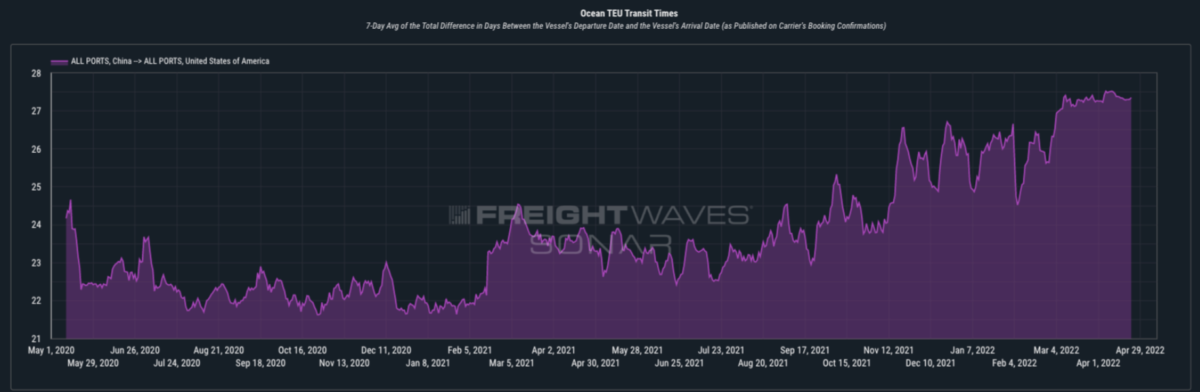

According to SONAR’s ocean intelligence dashboard, it currently takes 27 days for a vessel to travel from a Chinese port to a U.S. port. Since the volume of containers from China to the U.S. started its drop on April 6, it will likely be May 3 before U.S. ports experience a drop in volume.

It takes approximately 10 days to three weeks after a vessel arrives in the U.S. before the containers that traveled on board enter the domestic surface freight market. This would put a slowdown in trucking freight volumes related to Chinese imports between May 13 and May 24.

We have seen this play out before.

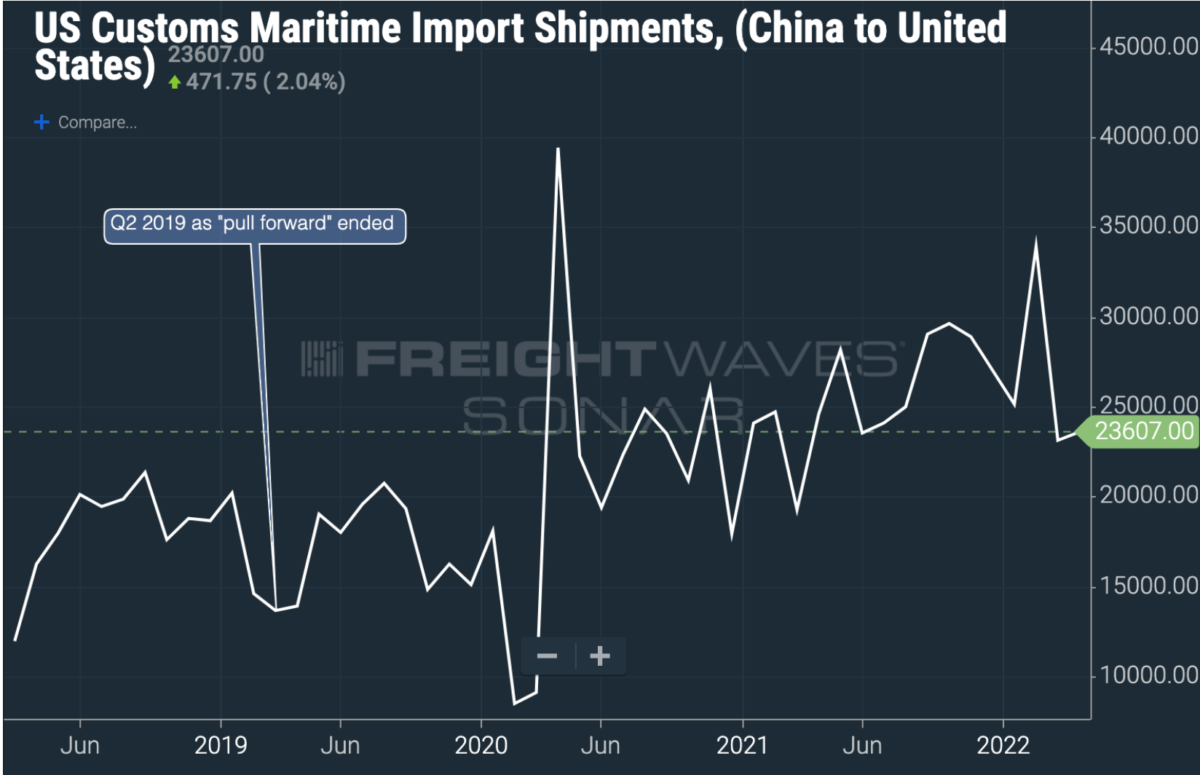

During the second half of Donald Trump’s presidency, the U.S. declared a trade war on Chinese imports. The first tariffs on Chinese goods were set at 10% and went into effect in December 2018. That was intended to be a shot across the bow and had little effect on import volumes. However, President Trump also threatened that if his demands for Chinese policy changes were not met, he would raise the tariffs to 25% by March 31, 2019.

Reacting to a threat that most importers and Chinese manufacturers thought had legitimacy, a surge of goods started to flow from China to the U.S. in what was described as a “pull-forward.”

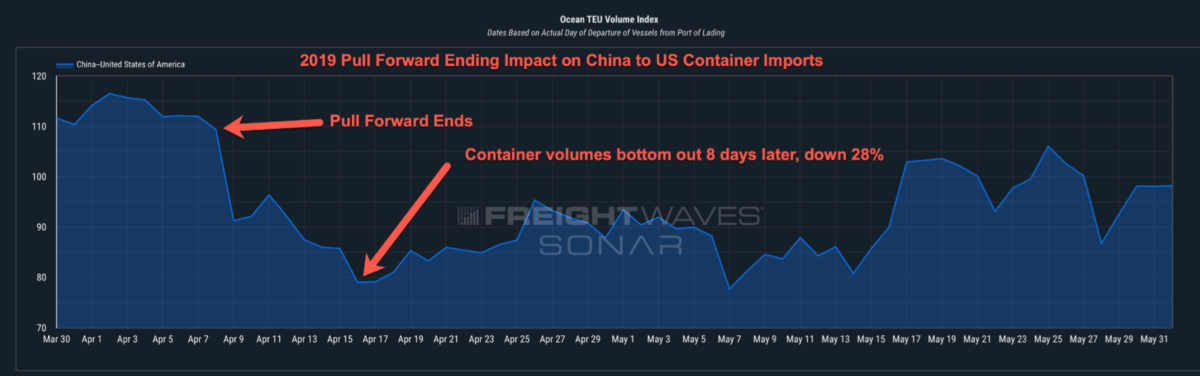

The last of the “pull-forward” surge containers to leave Chinese ports was on April 7, 2019. SONAR’s Ocean TEU Volume Index of containers leaving Chinese ports to the U.S. dropped by 28% from April 8, 2019 to April 16, 2019.

The first signs of U.S. trucking volumes dropping took place 35 days after the drop in container volumes out of China. From May 9, 2019, to May 16, 2019, U.S. national contract truckload volumes (OTVI.USA) dropped by 6%.

In Asian import-heavy Los Angeles, the drop was much worse. Truckload volumes dropped by an astounding 28% from May 8, 2019 to May 16, 2019. The drop was so significant that I wrote my first article warning of the freight recession and stated that “Conditions for fleets are deteriorating and it will get bloody.”

The recent drop in container volumes is eerily similar to the one that took place in 2019.

The drop in 2019 started with the same speed and depth as the one we are currently facing. The trucking industry had just come through one of the hottest freight markets in history in 2018, with more new fleets entering the market than in any previous period in history.

The abrupt drops in container outflows from China in 2019 and 2022 happened almost exactly three years to the day, which means the freight market seasonal calendar was roughly identical and makes for easy comparables.

Since April 2019, maritime shipments from China to the U.S. have grown by 28%, while U.S. truckload volumes have increased by 24% in that same timeframe.

A slowdown in freight volumes from China in May 2022 will be more equitably distributed throughout the U.S. and less concentrated in Southern California, as compared to the 2019 slowdown.

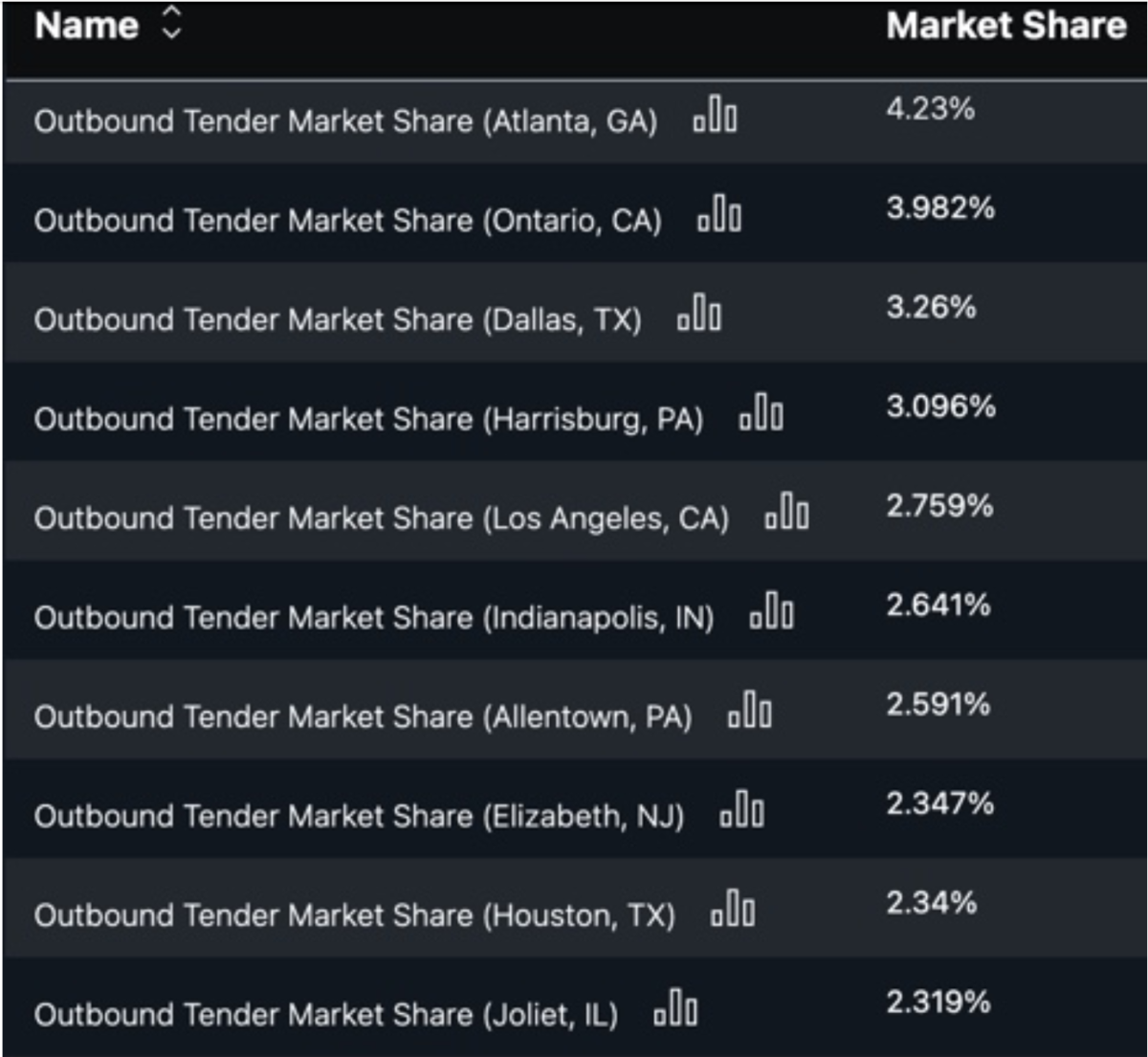

Why? While Southern California’s ports are still the primary ports of entry for Chinese goods, recent port congestion has encouraged importers to shift volumes away from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. This is showing up in SONAR’s truckload market share data (OTMS).

In April/May 2019, the Los Angeles and Ontario freight markets represented 7.69% of all U.S. contracted truckload shipments. Today, those two markets represent just 6.74%.

Watching daily market conditions will be critical to fleet operators in their search for headhaul markets. A headhaul market is a freight market in which there are more loads than dispatchable trucks. In SONAR, this map is updated daily and markets are shaded in blue. The deeper the blue, the better conditions for fleets.

We always coach trucking companies to go “blue to blue” to stay loaded, and since the data comes from tenders and not load board activity, it is far more accurate of current conditions in the market because it avoids “ghost loads” from brokers.

Eventually, the lockdowns will end and Chinese production will begin once again. However, the longer China stays offline, the longer it will take for production to ramp up. Supply chains don’t come online instantly.

And just how long it takes for the lockdowns to end and the supply chains to begin operating again is a guessing game. But there is reason to believe that the Chinese lockdowns are far from over.

FreightWaves’ Eric Kulisch reported on April 15, 2022, that BBVA suggested that the lockdowns in China could continue until June.

If this prediction plays out, it will be a difficult summer for many U.S. trucking operators.