“It’s like when you were a little kid and played a game where you laid siege to a castle and you surrounded it, trying to starve the people out. But in this siege — Russian sanctions — half the castle has been left unsurrounded. They can just open the doors and get resupplied with food and trade every day,” said Robert Bugbee, president of Scorpio Tankers (NYSE: STNG).

One year ago, Russia invaded Ukraine. Bugbee’s comments, delivered at the Norwegian-Hellenic Chambers of Commerce shipping conference last month, sum up how the war has played out for shipping markets and global trade over the past 12 months.

There have been a multitude of sanctions. Russia has indeed faced challenges importing and exporting. But cargo has continued to flow, like water drawn by gravity around a stone.

Cargoes either take a longer route, or a replacement source steps in. Across all the major ocean shipping segments — containers, tankers, dry bulk, gas — the first year of the war has shaken up markets but hasn’t stopped trade.

Container shipping

No matter the shipping segment, there are various reasons to stop serving Russia. There’s financial risk from actual sanctions in some cases, along with a desire to “self sanction” even if trade is allowed.

There is operational risk from ships getting delayed, a major issue for container shipping due to export-control requirements to inspect for forbidden dual-use (civilian/military) goods.

There’s also a moral aspect. Some shipping executives refuse to allow their companies to serve Russia because they believe it’s the wrong thing to do. And there are reputational reasons to abstain: financial fallout from being perceived by customers as supporting Russia.

Virtually all of the major container shipping lines suspended all service to Russian ports shortly after the war broke out and have not returned. Maersk and CMA CGM have divested Russian port holdings.

Mediterranean Shipping Co. (MSC), the world’s largest container shipping line, still serves Russia. “Connecting Russia to the world … MSC has been helping customers to ship cargo to and from Russia since 1998,” MSC boasts on its website.

As previously reported by Alphaliner, MSC now has the largest share in the Black Sea market, continuing to service Novorossiysk, Russia. After other mainline carriers besides MSC pulled out of Novorossiysk, Turkish short-sea carriers Arkas, Admiral, Akkon and Medkon boosted their own services to fill the gap.

Alphaliner reported in December that MSC increased its weekly Russia connections with a new South Turkey-Russia shuttle service.

On Friday, the one-year-anniversary of the invasion, MarineTraffic ship-position data showed the 2,598-TEU MSC Eloise at a berth in St. Petersburg in the Baltic Sea. The 2,490-TEU MSC Antwerp III was at a berth in Novorossiysk. The 2,024-TEU MSC Rhiannon and 2,045-TEU MSC Jenny II were just offshore.

There is no law or regulation that forbids MSC or any other ocean carrier from serving Russia.

On March 1, MSC announced a temporary stoppage of all bookings to and from Russia, excluding food, medicine and humanitarian goods. Bloomberg reported on MSC’s continued service to Russia in July. FreightWaves asked an MSC spokesperson on Thursday whether the booking halt had been lifted. The spokesperson referred FreightWaves back to the March 1 statement.

Meanwhile, as some carriers continue to provide links to Russian ports in the Baltic, Black Sea and Pacific, a surge in containerized cargo is simultaneously coming into Russia by land. Waiting trucks are lined up for miles at the border of Georgia and Russia, en route from Turkey and Armenia.

The New York Times reported that dual-use products are now flooding into Russia via China, Kazakhstan and Belarus, and that overall goods imports to Russia were back to pre-war levels as of December.

Containerized cargo has found a way around the obstacles.

Tanker shipping

The effect of the war on container shipping has been minor, because Russia is a relatively small market. Not so in tanker shipping.

Russia is the world’s second-largest exporter of crude oil and second-largest exporter of diesel. Tanker markets have been heavily impacted by the war.

Evercore ISI analyst Jon Chappell called the war “a generational geopolitical event that is likely to change seaborne flows of the world’s most important commodity for years.” Chappell believes “the redrawing of the global trade map has only entered the early innings.”

The EU banned imports of Russian seaborne crude as of Dec. 5 and Russian petroleum products as of Feb. 5. On the same dates, the European Union, G-7 countries, Japan and Australia banned provision of shipping services (including insurance) to tankers carrying cargo valued above a price cap to non-EU countries.

The cap plan is specifically designed to force Russia to sell its petroleum at a discount but keep cargoes flowing. To leave the doors of the castle open, in Bugbee’s words.

Most Russian cargoes are not loading aboard traditional tankers with standard U.K. insurance. Most are moving on tankers in the “shadow fleet” — vessels with opaque ownership that operate outside Western insurance and financial systems. “The transfer of ships into the so-called shadow fleet effectively removes them from the mainstream trades and reduces effective vessel supply,” said Kevin Mackay, CEO of Teekay Tankers (NYSE: TNK), during a conference call on Thursday.

In addition to the emergence of the shadow fleet, the other big consequence of the war is much longer voyage distances. The longer the voyage distance, the more tanker capacity is soaked up and the better for spot rates.

Russian crude that used to go short-haul to the EU now goes almost exclusively on long-haul voyages to China and India. Russian diesel that used to go to the EU is traveling much farther afield, as well.

“Africa and Latin America are likely to be key destinations for Russian clean products moving forward, especially for diesel and gasoil,” said Reid I’Anson, senior commodity analyst at Kpler.

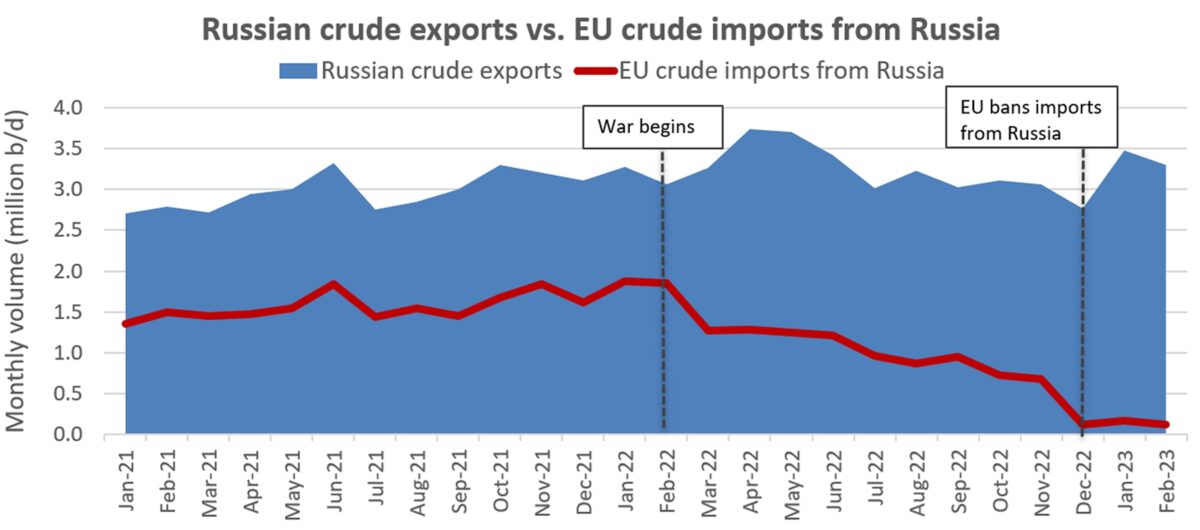

Kpler provided FreightWaves with its latest data on Russian seaborne outflows and EU inflows, including February’s month-to-date average.

Following the December EU sanctions, Russian seaborne crude exports averaged 3.5 million barrels per day (b/d) in January and 3.3 million b/d this month. That’s up up 6% from average volumes in the two months prior to the invasion.

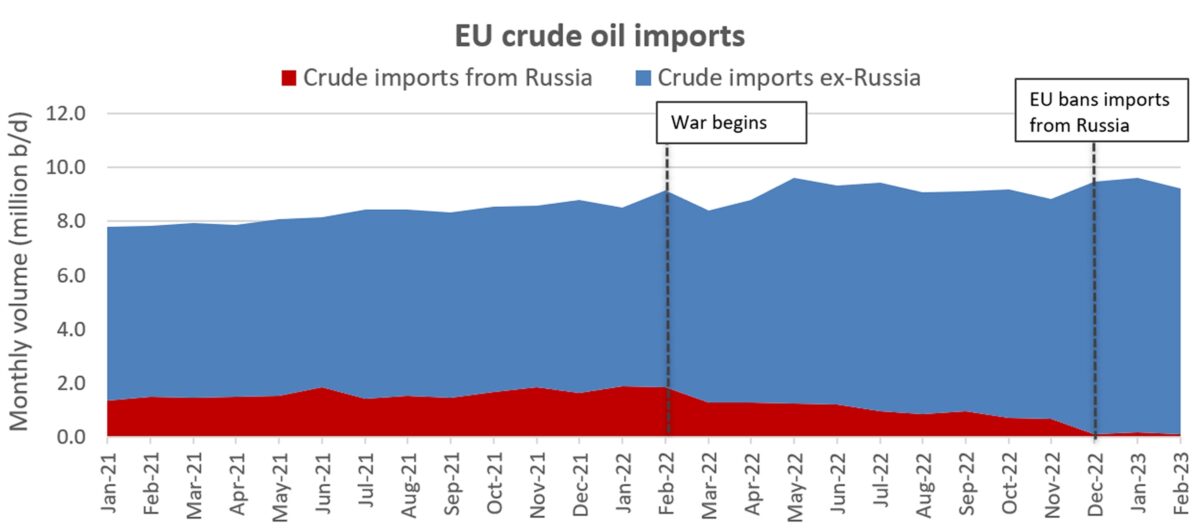

EU seaborne crude imports from Russia slowed to a trickle following the December ban, but EU crude imports overall are now higher than they were before the invasion.

According to Kpler data, the EU imported 9.6 million b/d of seaborne crude in January and 9.2 million b/d in February, up 9% from the average in the two months prior to the invasion.

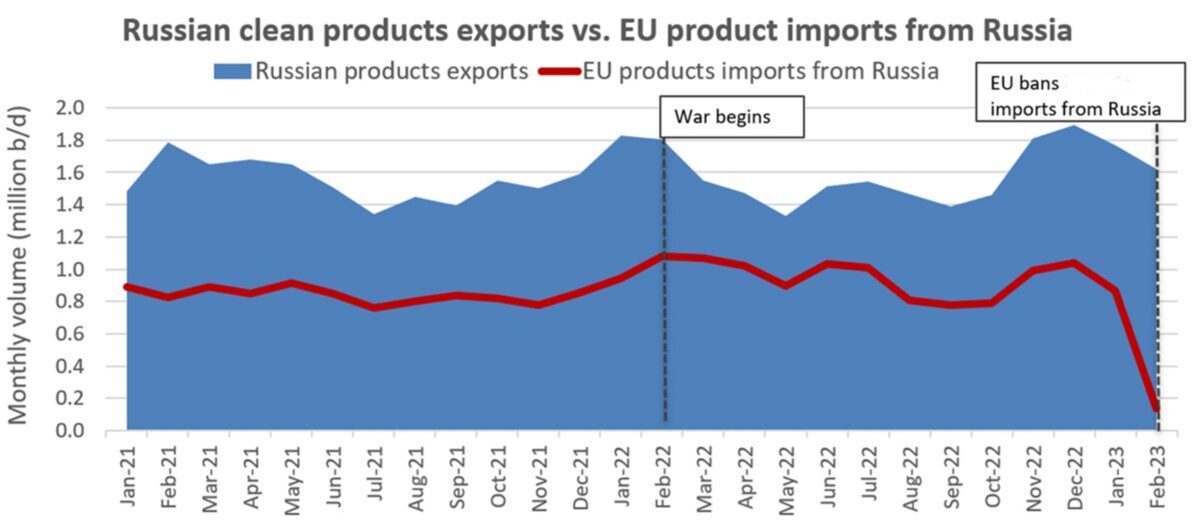

The EU ban on Russian products imports is less than a month old, so it’s still too early to know how that will play out.

I’Anson told FreightWaves, “It will generally be more difficult for Russia to find alternative buyers, relative to crude, especially for produced VGO [vacuum gas oil] and naphtha. Announced production cuts are likely a response to weaker refinery runs to come.”

Kpler data shows a drop in Russian petroleum products exports this month, coinciding with the EU import ban. Russian products exports are averaging 1.6 million b/d this month. That’s down 14% from the recent peak in December and down 11% from January 2022, the month prior to the invasion.

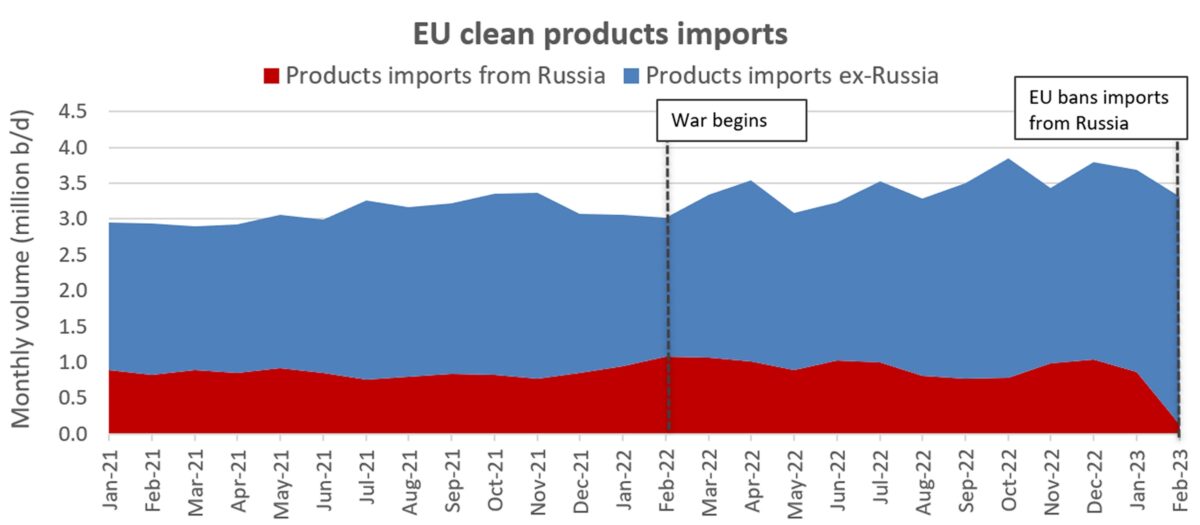

February refined products imports to the EU are averaging 3.3 million b/d. That’s down from recent months, but this is likely due to the EU loading up inventories before the Feb. 5 import ban.

During the 12 months since the war, average EU refined products imports were 11.5% times higher than they were in the 12 months prior to the war, according to Kpler data.

LNG shipping

The transport of liquefied natural gas, as with crude and products, has been profoundly affected by the war.

Pre-invasion, the EU countries — Germany in particular — were highly dependent on Russian pipeline gas. Russia appeared to use intentional reductions of its pipeline supply in an attempt to frighten the EU into not fully supporting Ukraine. Until September, when someone blew up the Nord Stream pipelines.

The loss of pipeline gas led to a scramble by Europe to find replacement supply. An armada of LNG carriers delivered cargoes from the U.S. Gulf last year. At the peak of the demand frenzy, spot rates for LNG carriers reached $500,000 per day, the highest day rate ever paid for any commercial ship in history.

In Shell’s annual LNG outlook, released this month, the energy giant said that Europe increased its LNG imports by 60% in 2022 to replace Russian gas. European demand pulled supply away from other countries such as Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.

“Russia’s invasion of Ukraine didn’t just affect Europe,” underscored Shell. “It impacted energy markets across the world. 2022 can go down as the year that reshaped global energy markets. The events of the year triggered structural shifts in market dynamics that may impact the long-term trajectory of the LNG industry.”

Dry bulk shipping

The dry bulk shipping sector has also been heavily impacted by the war. The global spotlight is particularly focused on lost Ukrainian wheat and corn export cargoes and their effect on world hunger.

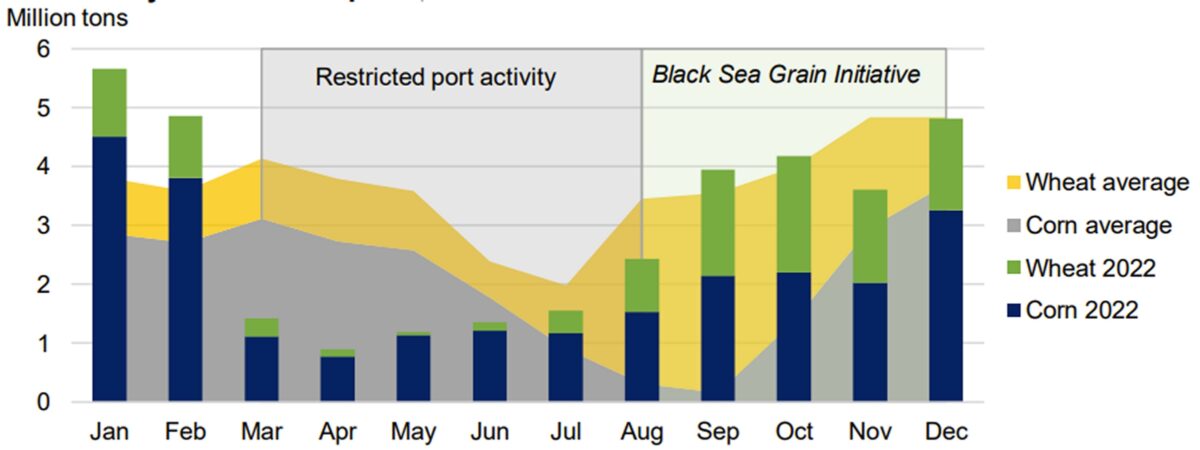

Petros Pappas, CEO of Star Bulk (NYSE: SBLK), said on his company’s latest conference call that the global grain trade declined 3.1% last year “as the war abruptly halted Ukrainian exports, which account for 10% of the total grain trade, for six month. From August onward, exports partially resumed through the Black Sea Grain Initiative.”

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) issued a report on the war impact in January. As a result of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, which allows bulkers to pass through the Black Sea (and which will expire on March 18 if not renewed), the USDA said Ukraine’s combined wheat and corn exports in September and October were higher than the five-year average. December volumes were on par with the average.

The USDA expects Ukraine to export 13.5 million tons of wheat in the 2022-23 marketing year, down 28% from 2021-22. However, it expects global exports to be up 4% year on year, largely due to a surge in exports from Russia.

The USDA anticipates Ukraine to export 22.5 million tons of corn in 2022-23, down 17% year on year. It predicts global corn exports will fall 13% in the current marketing year, but mostly due to declines from the U.S., not Ukraine.

The war effect on dry bulk goes well beyond Ukrainian grain exports. Russia is the world’s third largest exporter of coal. The EU has banned imports of Russian coal since August.

As natural gas prices surged last year, the EU ramped up coal imports from non-Russian sources (Colombia, South Africa, U.S., Australia) to a new high of 12.7 million tons in December, according to Mark Nugent, senior analyst at ship brokerage Braemar. EU coal imports were up 30.5% year on year in January.

Russia’s dry bulk exports have now followed the same script as Russia’s crude exports. Cargoes forsaken by the EU are going on long-haul voyages to China and India instead.

Nugent said that total Russian dry bulk exports (coal, grains, steel, fertilizer, etc.) averaged 23.8 million tons per month in the post-invasion period between March 2022 and this January, essentially flat with the same period the year before.

Russian dry bulk volumes to China rose 24.2% year on year and those to India “nearly tripled,” said Nugent. “India, in particular, has shown a willingness to buy cheaper Russian commodities, namely coal, to replace expensive alternatives from other sources such as Australia.”

Looking back on bulk commodity shipping flows over the first year of the war, ship brokerage BRS concluded, “What we have learned thus far [is that] despite incurring inefficiencies, the commodity markets — and the players behind them — are enormously flexible over time. This has made the desired effect of sanctions difficult to achieve.”

Bugbee made a similar point. “I am bemused with investor questions like ‘What is Russia going to do?’ This is the completely wrong way to look at it. Because the U.S., Europe, Australia and Japan may have sanctioned Russian supply, but nobody sanctioned South American, African, East Asian, European and North American demand.

“We have to look at the market from the demand side, not the supply side. If you do that, it becomes very simple,” Bugbee said. The cargo “is going to find a way to get there.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Welcome to the dark side: The rise of tanker shipping’s ‘shadow fleet’

- Sanctions effect begins: Crude tankers forced onto longer voyages

- Crude tanker rates down double digits after Russia sanctions debut

- Will sanctions on Russian diesel pay off for product tankers?

- Could Russia sanctions work in practice even if they fail on paper?

- Chaos theory: How tankers thrive amid energy crisis and war

David Dzidzikashvili

The Ukrainian military and political leadership have been able to fight the Russians and inflict devastating & catastrophic strategic losses on the Russian military. The capture of Kherson has been the biggest setback for Putin and the Russian Army, this was the first greatest strategic loss. The battle of Bakhmut is the second great loss for the Russians and it does not matter now if the Wagner terrorists can take over the remainder of the city, the Ukrainians have strategically won this battle too.

Within next weeks once the muddy ground gets dry and becomes more solid, the Ukrainians will be able to wage a massive counterattack involving and utilizing the newly delivered western tanks Challenger and Leopard 2 tanks and Bradley, Stryker, AMX-10 and Marder infantry fighting vehicles. These battle tanks and vehicles have much more superior firepower and high tech options vs. the Russian equipment. If Ukraine will have enough number of the tanks and fighting vehicles, they should be able to start a massive counterattack and liberate more of its occupied territories across Donbass, Luhansk and at a later stages Crimea.

The only strategy for the wanted war criminal Putin now is to keep inflicting massive civilian terror, casualties on the Ukrainians and keep attacking the civilian infrastructure to starve them and leave the Ukrainians without electricity or water supply. It feels like Putin is utilizing the usual Russian military playbook he used in Georgia, Chechnya, Crimea and Syria: win the war by spilling more civilian blood, inflict more civilian terror and keep committing more war crimes to further inflict more fear and terror.

Hopefully the NATO members, the US especially will be able to throw in more weaponry, especially the F-16 fighter jets, hopefully higher range MGM-140 ATACMS rockets, counter rocket C-RAM weapons systems to better fight the Iranian drones and more for air defenses to counter the Iranian drones and ballistic missiles.

With such phase this war will most likely end in 2023 or maximum with Crimeas liberation within few months of the start of 2024. The Russian forces will be also forced to leave Moldova, Georgian regions of Abkhazia and Samachablo (so called South Ossetia), Nagorno-Karabakh and Syria. Ukraine will be victorious and the Russians should be very concerned about the fate that awaits afterwards. With the Ukrainian victory the world will forever destroy Russia’s imperialistic ambitions, Russian nationalism and this will save future generations from future wars and peace will definitely follow.