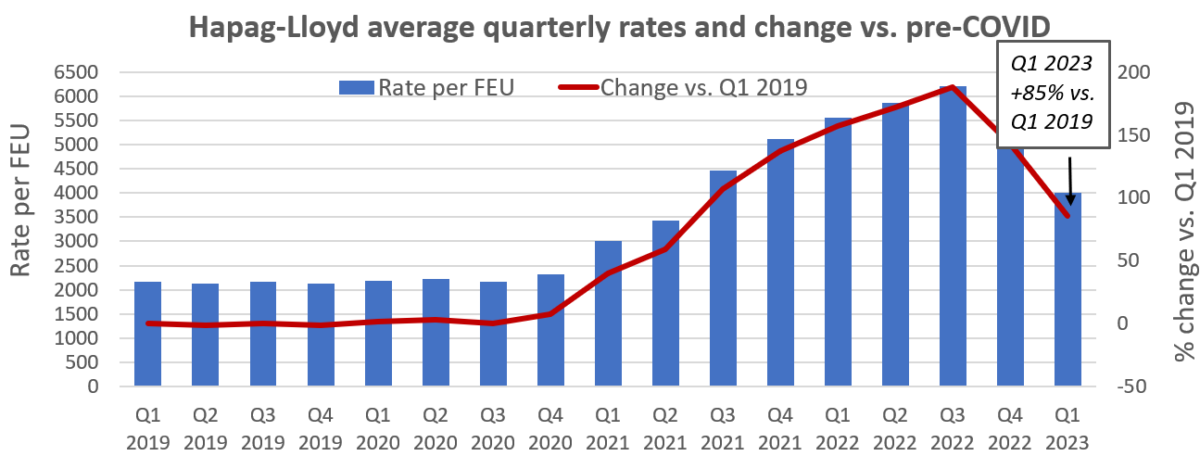

Germany’s Hapag-Lloyd, the world’s fifth-largest shipping line, posted better-than-expected results for the first quarter of 2023, with freight rates averaging $3,998 per forty-foot equivalent unit, 85% above pre-COVID levels.

“Volumes remained subdued as the inventory correction starting in the second half of last year continued, but the numbers started to look a little better toward the end of the quarter,” said CEO Rolf Habben Jansen on Thursday’s conference call.

“We think it’s going to remain subdued [in the second quarter] but I do believe the second quarter will be better than the first. I don’t think that means we’re now going to see a very quick recovery, but I do think it underlines the point that destocking is slowly but steadily coming to an end, and at some point in time, we will quite likely see a bit of a pickup in demand.”

Cargo volumes dropped sharply in the second half of last year. Habben Jansen predicted that “at some point, probably in Q3, [volume] will cross into year-on-year growth,” with full-year totals coming in close to or slightly above 2022 levels despite low first-half demand.

‘We are still wrapping up negotiations’

Spot rates have been below breakeven for carriers in the trans-Pacific and Asia-Europe trades, he said.

“Right now, we see spot rates being very, very low in a number of the headhauls. If we see a bit of an uptick in seasonal demand going into peak season, I expect to see a bit of a recovery in those spot rates, for a number of months, probably starting toward the end of Q2 [and lasting] at least until Golden Week [the first week of October].”

Average rates — including both contract and spot — are set to fall further starting in the second quarter due to renewals of annual trans-Pacific contracts at much lower levels than last year.

Trans-Pacific contracts generally run from May 1 to April 30, but Hapag-Lloyd has yet to finish talks. “We are still wrapping up negotiations as we speak,” said Habben Jansen. “Negotiations on the trans-Pacific have not been easy this year.”

He confirmed that contracts that have been signed are at rates above loss-making spot levels. “Some of the spot rates have gone to levels that do not make sense, because you simply lose too much money. We do not close contracts for 12-month durations if we know up front that we are going to lose a significant amount of money. So yes, most of the contract rates have been closed at levels that are definitely above spot levels.”

Why rates could increase despite capacity deluge

In the medium and longer term, the big challenge for shipping lines is the orderbook. An unprecedented amount of new capacity is being delivered starting this year and continuing through 2025. “It is a very significant orderbook. There are quite a lot of ships in the pipeline,” said Habben Jansen.

Although deliveries started ramping up in March and are now in full swing, he believes capacity pressure won’t peak until next year. “For 2023, I think the effect is still manageable because quite a lot of new ships won’t come until the second half. But certainly for the next two years, it will put pressure on the market. When we look to 2024 and 2025, the likelihood that supply growth will outpace demand growth is high.”

Despite these supply pressures, he argued that market forces will push freight rates up to levels that cover higher carrier costs. “When you look at rates falling back to pre-COVID levels, those rates are not sustainable in the long run because costs have come up. The reality today is that everybody faces costs that are 25-30% higher [than before the pandemic].

“If you look back in history, there have only been short periods of time when rates were really far below costs. That is because 65% of the costs of every voyage are variable costs. As soon as the market drops too much, carriers will start taking out costs [by canceling sailings]. Over time, that helps rates go back to a level that is at least at or hopefully slightly better than costs.

“So, your long-term outlook on rates should be that they will remain 25-30% above what we saw in 2018-19 simply because if they don’t, we would end up with a lot of cash-negative shipments. And with 65% of the costs being variable, we would have to take action to mitigate costs.”

Why rates could stay low for longer

At least, that’s Habben Jansen’s theory. The counter argument is that the liner industry did indeed suffer extended losses in the decades prior to the COVID boom. Carriers were able to survive years in the red, in some cases due to government support.

And this time around, carriers are flush with billions in windfall cash from the boom, so they can more easily sustain prolonged losses. As Sea-Intelligence CEO Alan Murphy told Splash, “The only thing that scares me more than shipping lines without money is shipping lines with money.”

Regarding losses in earlier eras, former APL CEO Ron Widdows said during a Marine Money conference in 2014: “With the structure of the companies — some of these are state-backed, some quasi-state-backed — the operating philosophies and how they price and how they view returns are different.

“Those with state backing don’t necessarily have to generate the kind of returns a stand-alone company or a publicly listed one has to generate,” said Widdows.

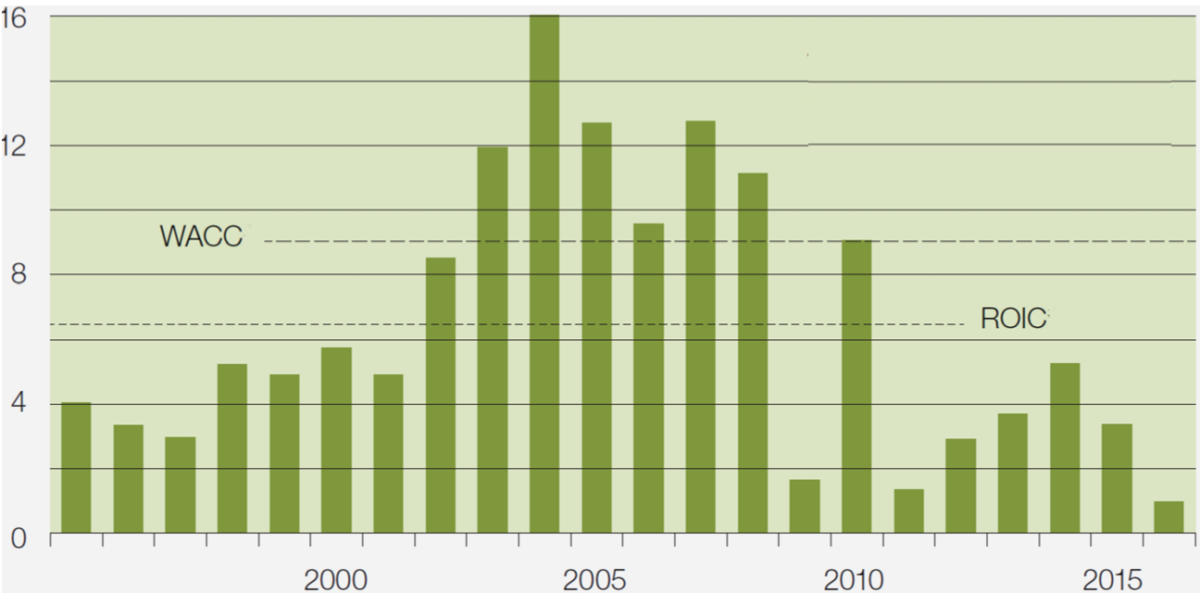

“The container sector hasn’t made its cost of capital during the past decade, or for any decade you want to look at,” he said of pre-2014 returns (referring to a period when the industry was much less consolidated than it is today).

McKinsey & Co. estimated in a report published in February 2018 that ocean carriers “destroyed over $100 billion in shareholder value over the last 20 years.”

The consultancy noted that the liner industry’s profitability “was particularly poor between 2011 and 2016, when the industry average return on invested capital was consistently lower than the weighted average cost of capital.”

Q1 results far surpassed pre-COVID results

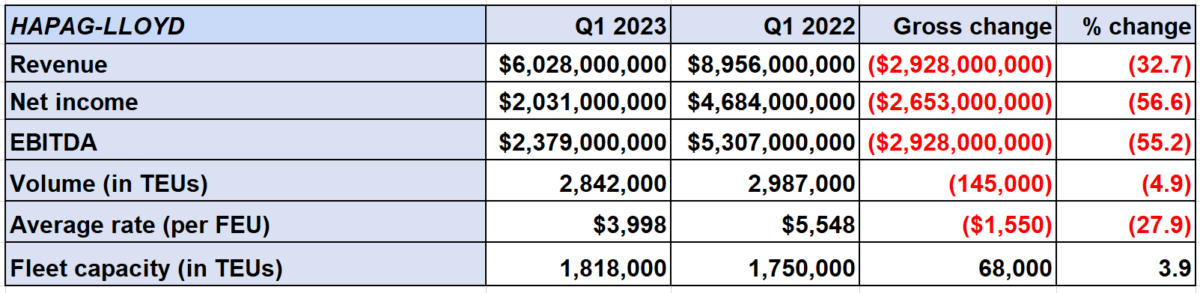

Hapag-Lloyd reported net income of $2.03 billion for Q1 2023, down 57% year on year. Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization came in at $2.38 billion, above analysts’ forecast for $2.1 billion. Earnings before interest and taxes totaled $1.87 billion, topping the forecast for $1.6 billion.

Results for Q1 2023 were “a solid beat of 12% at the EBITDA level and 19% at the EBIT level,” said Deutsche Bank analyst Andy Chu.

According to Habben Jansen, “The financials are quite exceptional if you look at them in a historical context.”

Comparing Q1 2023 to Q1 2019, pre-COVID, net income was 19 times higher in the latest period, driven by the 85% improvement in average rates. Hapag-Lloyd’s EBIT margin (operating profit as a percentage of revenue) was 7% in Q1 2019. In the latest quarter, it was more than quadruple that: 31.1%.

In early March, Hapag-Lloyd introduced its full-year 2023 guidance for EBITDA of $4.3 billion to $6.5 billion and EBIT of $2.1 billion to $4.3 billion. It made no changes to that guidance on Thursday.

Given that Hapag-Lloyd earned 44% of the full-year EBITDA range midpoint and 58% of the EBIT midpoint in the first quarter alone, the maintained guidance implies a steep earnings decline ahead. Even so, if the carrier does hit its target, 2023 would be the third-best year in the company’s history.

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- US imports up again in April as market mirrors pre-COVID ‘normal’

- Maersk: Downturn on predicted course, liners acting ‘rationally’

- Container shipping warning: Green shoots are ‘transitory illusion’

- As Asia-US shipping rates rise, so does skepticism on staying power

- Container shipping sees signs of a bottom (at least, for now)

- Mixed signals: Container shipping downturn not following the script

- ‘Colossal’ tidal wave of new container ships about to strike

Balance

you’d think this to be true, although from my experience when shipping rates go up, prices in stores don’t move much.

When rates go down, prices in store sky rocket upwards. never makes sense.