“It’s the worst freight market since the Great Financial Crisis.”

This statement is commonly heard on our channel checks among carrier and broker executives and often repeated on social media. Now we have some evidence to support it.

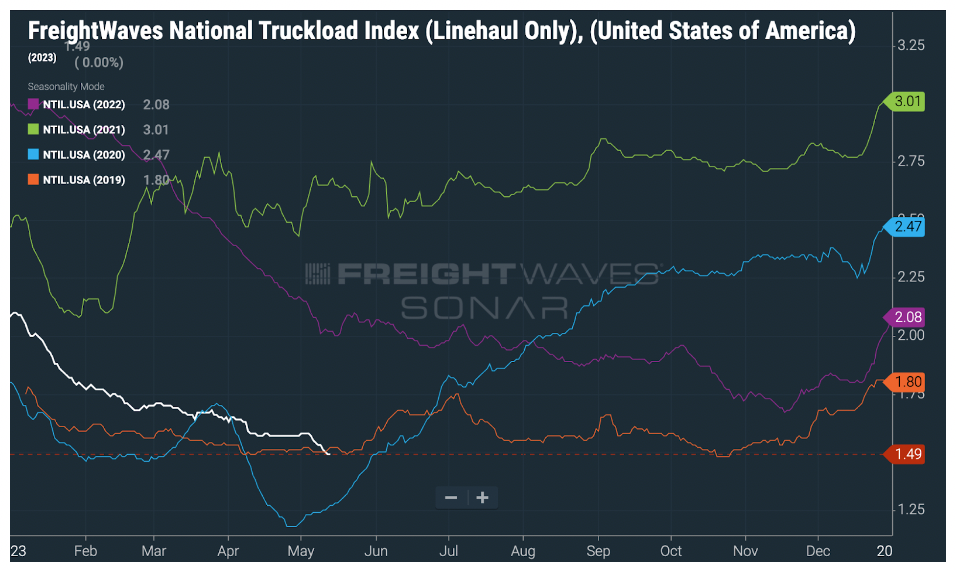

The National Truckload Index (NTI), available on SONAR, which measures the average national truckload spot rate, is $1.49 a mile, breaking below the 2019 seasonal equivalent.

While extremely low rates are bad enough on their own, the worse news is that operating costs for trucking companies (not including fuel) are up more than 30 cents a mile in that same period. Operating expenses include maintenance, insurance, driver salaries and equipment.

On a cash flow-adjusted basis, current spot rates are equivalent to $1.19 a mile, without including any increases in the cost of capital to finance operations.

Where are the bankruptcies?

With the soft market conditions and low rates, where is the surge in 2023 bankruptcies?

While we know that thousands of small carriers have revoked their operating authority, we have yet to see a rash of bankruptcies in the truckload industry.

So far in 2023, FreightWaves has reported on only seven bankruptcies, a little more than one a month. The worst trucking market prior to the current one was in 2019, the “Trucking Bloodbath.” At one point, FreightWaves reported on 10 trucking bankruptcies in a single week.

New England Motor Freight’s (NEMF’s) bankruptcy opened the year (3,000 employees) and Celadon’s shuttering (5,500 employees) ended it. There were hundreds in between.

Is this a function of trucking companies doing so well during the COVID economy that they were able to pad their balance sheets and prepare for a massive downturn?

If so, it may mean that capacity stays in the market longer than in a typical down cycle.

Tender rejections show how dire conditions are in the freight market

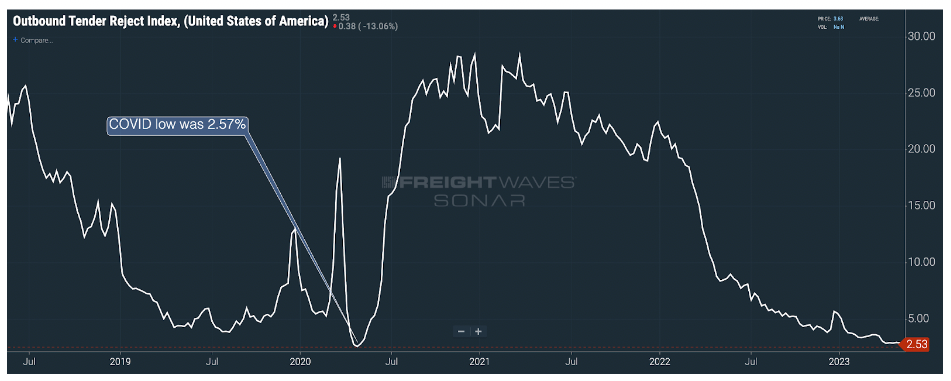

Tender rejections have dropped to an all-time low of 2.53%. The previous record low was set during the COVID lockdowns at 2.57%.

What is a tender rejection?

A tender rejection measures the balance of supply and demand in the trucking market.

A high rejection rate means that trucking firms have a lot of discretion on what loads they will take. Carriers want a high rejection level. It gives them a lot of choices on loads and drives up rates.

A low rejection rate is the opposite. It means that the carriers have few loads to pick from and are taking almost anything, without consideration of where it is going and at what price.

A rejection rate that is this low is significant because it means that carriers are struggling to find load opportunities and have lost pricing power.

Even though we are talking about freight, let’s look at this in the context of dating

When feeling desperate — you swipe right on everyone, without considering the quality of those prospects — you have a “low rejection rate.”

When feeling “hot” — you swipe left often and are highly selective — you have a “high rejection rate.”

It’s the same idea, just applied to “freight tenders,” not “Tinders.”

There are reasons to expect things could get worse

We know that a lot of the weakness in trucking is related to the expansion of capacity over the past few years.

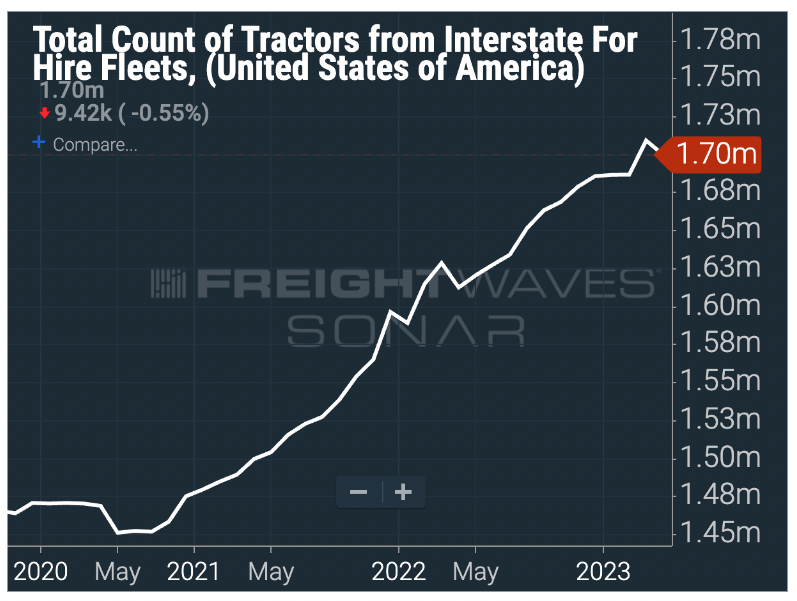

The total number of registered Class 8 vehicles in the over-the-road truckload industry grew from 1.47 million in February 2020 to 1.7 million as of April 2023. This 16% increase in capacity is a primary reason that freight feels so soft in the carrier community.

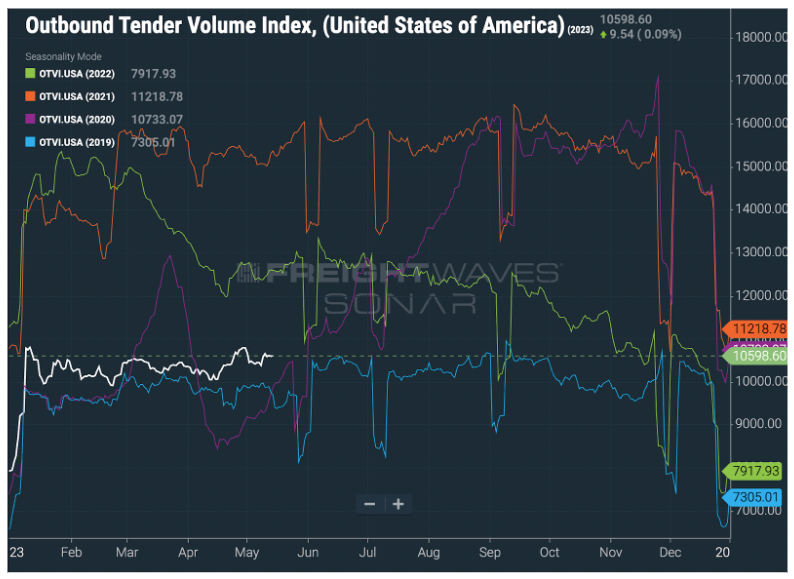

Volumes, on the other hand, are relatively stable, at least for now.

After coming down significantly over the past year, outbound tender volumes have shown a greater degree of seasonality than we’ve seen since 2019. The Outbound Tender Volume Index, which measures volumes in the truckload market, is down 18% from a year ago but up 6.8% since May 2019.

The softness that the market is currently experiencing is related to too much capacity that chased strong market conditions during the COVID economy that has now come back to earth.

If volumes were to fall further, it could get even more challenging for the trucking industry

The conditions in the freight market are dependent upon the balance of supply and demand.

Any slowing of freight demand will have a negative impact on the economics of the industry. During the COVID economy, government stimulus drove a lot of goods consumption, and thus freight demand.

The government debt ceiling debate currently hangs over Washington, with no real visibility on whether this will get resolved or how painful it will be. Federal government spending is 25% of GDP, so any delays to resolving this matter will most certainly be felt in the economy. Government employees, contractors and vendors will be significantly impacted, along with entitlement program payments.

This isn’t the worst outcome.

The nightmare scenario — one that causes the U.S. government to default on its debt — would roil financial markets, potentially causing one of the worst financial crises in history. This is such a doomsday scenario that it defies forecasting and prediction and isn’t even worth diving into.

But there’s something looming over the economy this summer with a far more certain impact.

A FreightWaves analysis found in March that federal government programs boosted personal income by an estimated $2.3 trillion from March 2020 to December 2022. According to The Motley Fool, consumers received an average of $3,450 in stimulus during the COVID economy. This included direct payments into bank accounts, an expanded Child Tax Credit and an expanded Earned Income Tax Credit.

We know from our freight data models that freight demand saw substantial increases in the weeks following government stimulus payments being transmitted.

Consumers with student loan debt were able to save, on average, more than $15,000 since March 2020 — and that’s about to end

One of the biggest COVID-related stimulus programs is not factored into our analysis or Motley Fool’s numbers: student loan forbearance. Since student loan payments were put on hold and not forgiven, neither FreightWaves nor Motley Fool calculated these as part of its consumer stimulus estimates.

Education Secretary Miguel Cardona said the student loan deferment program will end no later than June 30, 2023, and payments are expected to resume by Sept. 1, 2023. The amount of money we are talking about, in excess of a trillion dollars, is staggering. Student loans represent 7% of U.S. GDP.

Sixty-four percent of the $1.7 trillion in student loan debt remains in forbearance, amounting to $1.1 trillion. Many of the 25 million Americans who have deferred payments for student debt are aged 18-44 years old, one of the most important demographic groups that drive consumer spending.

According to a New York Federal Reserve Study, the average student loan payment is $393 per month. The original forbearance program was instituted by President Donald Trump at the beginning of COVID in March 2020.

For consumers taking advantage of the program, they have deferred 39 months worth of payments, resulting in more than $15,327 in additional discretionary income during the period, much larger than the amount most consumers received from other COVID stimulus programs.

The forbearance program, when originally conceived, was intended to be a short-term program to protect consumers from the COVID black swan event. But many consumers made financial decisions based on this short-term cash flow boost, treating the cash as permanent.

The Biden administration has been working to forgive up to 30% of outstanding student loans, but that is currently in doubt, with the Supreme Court expected to rule within the next month that the president lacks the authority to cancel the debts.

Because the president has been signaling a desire to cancel student loans and consumers have not had to make payments for over three years, the resumption of payments will come as a personal cash flow shock to many households.

This couldn’t come at a worse time

For the past few months, we’ve heard carrier executives predict that the second half of the year is going to be much better than the first half.

They often base this assumption on the expectation that the excess in retail inventories accumulated in the supply chain bullwhip will have burned off by the end of the summer.

There is good reason to endorse this view. Most of the excess inventory was ordered at least 18 months prior, and retailers have been pulling back significantly since they recognized they had a problem in Q1 2022.

But consumers are facing financial stresses from a lot of different directions.

Inflation has the biggest impact on the same consumer segment that holds the majority of student loans. These consumers have already maxed their available credit.

A sudden increase of $393 per month will force consumers aged 18-44 years old to cut back on discretionary spending. Since portions of this demographic have a tendency to prioritize experiences over goods consumption, we can expect this will have a much bigger impact on freight demand in the coming months. Last week’s April senior loan officer opinion survey indicated that lending standards continue to tighten and loan demand is weakening, both of which augur poorly for future consumer spending as well.

Colder temperatures are coming for the freight market — just in time for July. The “worst freight market since the Great Financial Crisis” may get worse.

Interested in the data presented in this article? SONAR is the world’s leading freight market intelligence platform, offering high-frequency freight rate and demand forecasting data. To learn more, visit sonar.freightwaves.com to sign up for a demo.

Stephen webster

In ont Canada a number of larger trucking companies are trying to push out small trucking companies and owner ops with their own running rights. We need min freight rates and stop bringing in low wage foreign truck drivers who can not read or understand English. All truck drivers should be hourly paid at a least 21 U S or 28cd per hour with overtime after 9 hrs driving or 10 hrs on duty

David

Normally I say pay your bills. But I’m so tired of everyone coming to this country legally and getting everything for free. They get free money and Healthcare to say the least. They get to start businesses and buy trucks and not pay taxes for years. God forbid the government wipe out some of the American student loan debt and help out American people. Thats one reason all these foreigners haul freight so cheap and mess it all up for the rest of us. They dont pay out as much as the rest of us.I’m just venting. And I’m not a supporter of the current administration.

Willy

It would appear that rates are starting to raise. In California truckload refrigerated rates have start to sky rocket. We are starting to see

higher rates Country wide in all areas for truckload, LTL, dry van & flatbed. Many shippers are and will start feeling the heat going forward.

Rene

I’ve always felt, that during the pandemic, just shutting down the country, quarantine crap, is, to me, giving up a fight! I didn’t and still don’t understand devastating our country’s economy would rid the nation of COVID(personally, I think is BS). I thought educating, guiding our nation on how to solder through a pandemic would have been a better route to take. All I see now in our country, is a weaker work ethic than ever before! From fast food to police, from grocery stores to construction, you name it, I see it has suffered in quality of work…

The term, “Going to Hell in a Hand Basket” is what’s happening!!!

I guess what I’m trying to say is, this seems to stem from the way our nation handled the Pandemic crisis, with no thought or care about our nations economy and the devastating outcome it is having on our people…