The extraordinary length of the trucking downturn is best explained by a government program that flooded small carriers with tens of billions of dollars of cheap, long-dated credit.

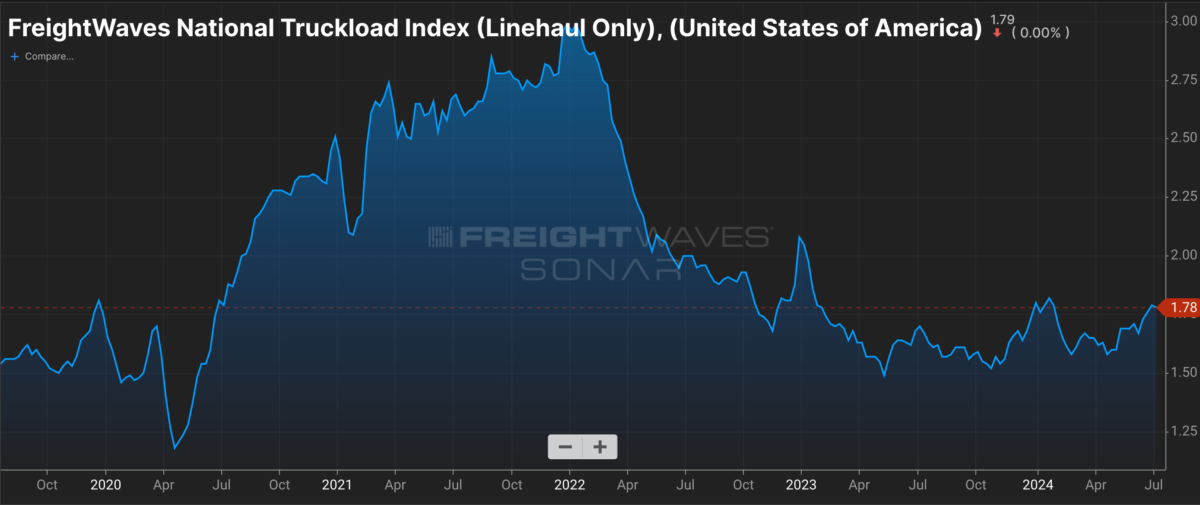

The persistence of the post-COVID trucking capacity overhand has perplexed industry observers for more than a year now. After the pandemic demand boom faded, there were too many trucks and not enough freight, and rates fell through the floor, bottoming around $1.49 per mile, exclusive of fuel, in May 2023.

Trucking carrier executives expected the rest of the cycle to play out according to a familiar script: As rates fell below carriers’ operating costs and stayed there, small fleets and owner-operators would be forced out of the market. The overall amount of trucking capacity would contract, the balance between supply and demand would be restored, and rates would rise once more.

Instead, carriers hung around for far longer than anyone anticipated, keeping rates lower for longer. A full year after the market’s bottom in May 2023, rates had only increased by about a dime, to $1.60 per mile.

Everyone wants to know when the market will heat up again, but to make that call, analysts have to know what’s causing the prolonged downturn in the first place. Plenty of theories have been offered, from operating efficiencies gained from technology to the growing market share of freight brokers, but none of these explanations so far have seemed sufficient to explain the strange shape of the current trucking cycle.

Until now.

Following a hunch, FreightWaves corresponded with the Small Business Administration (SBA) about the COVID-19 Economic Injury Disaster Loan (EIDL) program it launched in the early days of pandemic. The program was intended to alleviate the economic injury to small businesses caused by the pandemic and offered long-dated business loans at very low interest rates. Beginning in March 2020, small businesses could get loans of up to $500,000 on 30-year terms at a fixed interest rate of 3.75%. Given that the current yield on 20-year Treasury bonds is 4.57%, these loans were effectively free money, at least in the short term.

In September 2021, the ceiling was raised to $2 million, and by Jan. 1, 2022, the program had run its course and stopped accepting new loan applications.

In just under two years, the SBA injected approximately $390 billion of inexpensive credit into the economy, bolstering small businesses’ balance sheets and allowing them to survive the pandemic.

FreightWaves asked the SBA how much money went to transportation companies. The answer came back: $37 billion was lent to the transportation and warehousing sector (NAICS Sector 48-49) across 419,500 loans for an average loan amount of $88,200. In sector 48-49, there are 723,573 total businesses employing a total of 726,238 people. Of those people working in the sector, 539,702 work at firms with only 1-4 employees. In other words, the majority of the sector is composed of small businesses, and 58% of them received COVID EIDL loans.

Calculating the impact

Let’s do a little back-of-the-envelope math to put that number into context. First, we’ll look at it from a microeconomic perspective, then from a macroeconomic perspective.

An owner-operator driving 600 miles per day (a generous estimate), for five days each week will run 3,000 miles per week. At 50 weeks per year, that’s 150,000 miles. Let’s assume that spot rates inclusive of fuel are approximately $2.25: That comes to $337,500 in gross revenue per year. Without doing separate calculations for all of the trucker’s costs, let’s assume he achieves a 95% operating ratio after paying his own wages: That comes to $16,875 in operating income per year.

Small carriers operate on thin margins. To get a more realistic picture of the owner-operator’s take-home pay, we can add back his wages, which we’ll peg at 50 cents per mile, or $75,000. If he doesn’t reinvest his operating income back into his capital and lets his equipment depreciate, he can “take home” $91,000.

A loan of $88,000 would let an owner-operator whose earnings have been cut in half, from $91,000 to $45,500, continue to operate for two years without feeling any effects at all.

Trucking costs in the United States total about $800 billion annually, and approximately half of that is revenue to the for-hire trucking industry (as opposed to private fleets wholly owned by shippers). If we take the for-hire segment’s $400 billion in revenue and assume the same 95% OR, then the for-hire segment’s total operating income comes to $20 billion. The COVID-19 EIDL program’s $37 billion exceeded the annual operating income of the for-hire trucking industry, and the same math works: The industry’s profits could be cut in half by a severe freight recession and carriers’ balance sheets would remain unaffected for years.

Bolstered by an infusion of cheap cash, carriers have been able to continue operating in adverse business conditions that normally would have forced them out of the market, which has ironically prolonged the low rate environment.

In our view, given its vast scale, the SBA’s COVID EIDL program is a sufficient explanation for the unusually long downcycle the trucking market has experienced since 2022.

What happens next?

But the bill is coming due. In 2023, the Biden administration floated a policy proposal that would have kept the government from pursuing collection on delinquent COVID EIDL loans less than $100,000, but the inspector general of the Treasury Department objected, arguing that it would incentivize further delinquencies. In May 2024, the Small Business Administration reversed course and said that it would begin referring delinquent loans to the Treasury Department and IRS for collection.

It’s unclear what the impact of the government’s efforts to collect these loans will have on the trucking market. While the smallest COVID disaster loans were unsecured, loans above $25,000 required collateral, and loans exceeding $200,000 required borrowers to use their primary residence as collateral. Loans between $25,000 and $200,000 required collateral, but borrowers could use other assets of equivalent value in lieu of their primary residence – for instance their trucks. Truckers whose houses are on the line may stay in the industry even longer if they figure it’s the best way to pay back their SBA loans.

Besides loan repayment, another clock is ticking: the depreciating asset of the trucks themselves. Between years three and five, maintenance costs on trucks tend to increase dramatically; the trucks require engine rebuilds and suffer more unplanned maintenance events and downtime. There’s a real possibility that the small fleets and owner-operators kept afloat temporarily with an infusion of SBA cash will not be able to afford to replace their aging equipment. It’s been four years since the beginning of the SBA COVID EIDL program, so the horizon for replacing trucks bought in 2020 is fast approaching, if not already here.

Lack of capital and inability to replace or maintain aging equipment, coupled with loan repayment, could accelerate carrier exits from the market. The used truck market would become oversupplied, putting downward pressure on asset prices and affecting the balance sheets of publicly traded carriers. Vendors heavily exposed to the small carrier market, from factoring companies to software providers, may see significant churn in their customer base.

This harsh reversal of carriers’ fortunes may very well lead to another capacity crunch, less pronounced than the COVID-19 boom times but stronger than other historical cycles — think of it as a pandemic aftershock. There are signs that the trucking market is already heating up, as tender rejection rates broke 6% in the past week for the first time since early 2022.

If the COVID money finally runs out and reality hits underperforming small carriers, the trucking market could undergo a dramatic whipsaw in 2025.