Before coronavirus, there was norovirus. Thousands of cruise passengers fell ill each year. “Cruises from hell” blared headlines alongside eye-catching pictures of giant ships. In fact, the vast majority of people sickened by the bug weren’t infected on cruises, but given the media spotlight, norovirus became widely known as the “cruise virus.”

Now we have more eye-catching pictures of giant ships in the news: this time, images of anchored container vessels stretching to the horizon alongside headlines about supply chain chaos, consumer price inflation and emptying store shelves.

Which raises the question: Does higher container shipping pricing actually cause inflation for U.S. consumers? And if not, will container shipping be associated with inflation anyway, given the media glare, like cruise lines with norovirus?

‘Human nature demands a scapegoat’

One reason cruise lines got stuck with their norovirus stigma was data visibility — numbers that went along with the pictures. Cruise lines were the only entities required to report norovirus cases and the Centers for Disease Control publicly posted the tally.

Container line quarterly results offer similar data visibility. The COVID era has been a gold mine for carriers, who are reporting the highest profits in the history of container shipping. Ocean carriers are on track to make $150 billion this year and another $150 billion in 2022, according to consultancy Drewry.

“An important point to stress — particularly now as the mainstream media seem to be latching onto the story more — is that human nature demands a scapegoat,” said Simon Heaney, senior manager of container research at Drewry, during a presentation last week.

“I think it’s natural with the profits the carriers are reporting that most of the ire has been thrown their way, particularly by BCOs [beneficial cargo owners],” Heaney added.

“But in our view, carriers are not to blame for this situation. It’s not their fault that ports keep them waiting and sailing schedules are in disarray. Nor is it the fault of the ports that they’ve become parking lots for ships and boxes due to fewer truck drivers available and lower amounts of warehousing space. This situation was not caused by a single sector and neither can one group fix it alone.”

According to Jason Miller, associate professor of supply chain management at Michigan State University’s Eli Broad College of Business, “People love blaming things on other factors.” He called the spotlight on ocean rates “a classic case of ‘I want to be able to attribute this to another entity because it makes me feel less to blame.’”

Miller, who believes that current inflationary pressures are driven by commodity prices, not ocean rates, said, “The problem now is that the visibility of this [ocean shipping congestion] is attracting people to it as an explanation for inflation, and to me, assigning inflation to this doesn’t make sense.”

Links between supply chain crunch and inflation

Shipping costs could temporarily boost inflation, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

It said, “The empirical approach to answer this question: first, quantifying the pass-through of shipping costs to merchandise import price inflation, and second, assessing the transmission of import price inflation to consumer price inflation.”

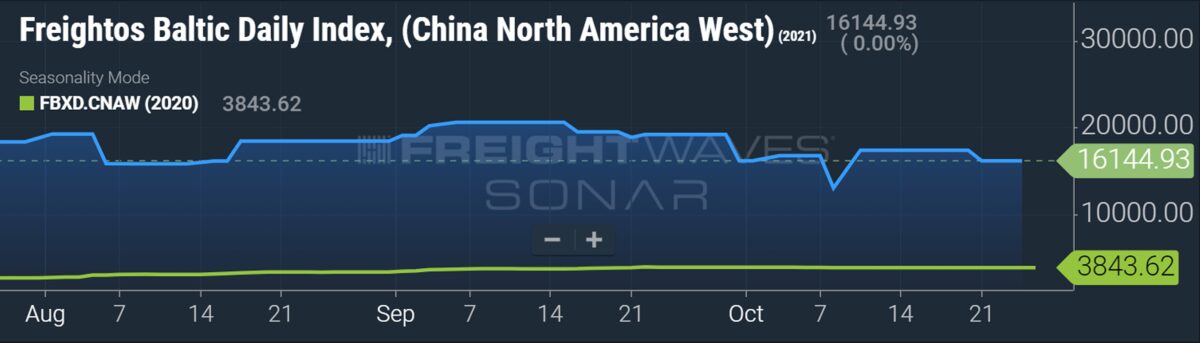

The evidence for import price inflation: Both ocean shipping contract and spot rates are up sharply. Data provider Xeneta estimates that Asia-West Coast contract rates have doubled year on year, to $4,000-$4,500 per forty-foot equivalent unit. According to the Freightos Baltic Daily Index, spot rates in that lane are at around $16,100 per FEU, more than quadruple spot rates at this time last year.

How that translates into import price inflation hinges on what’s in the container and who the importer is. If the box is full of bulky sofas and shipped at spot rates, the effect may be huge; if it’s full of iPads or high-margin designer shirts and moving at a contract rate, it’s not.

CEOs on quarterly calls are clearly making the connection between supply chain costs and higher consumer prices.

On the Oct. 19 call by Procter & Gamble (NYSE: PG), executives predicted $2.1 billion in incremental commodity costs in the current fiscal year (which started in July), plus $200 million in incremental freight costs, which will be partially “offset with price increases.” The company said it continues “to see pressure on transportation and warehousing” and has already announced price increases for nine out of its 10 product categories to offset these costs, with most price increases going into effect last month.

During Thursday’s call by Crocs (NASDAQ: CROX), executives cited “higher global logistics costs” and conceded that they “definitely have product on ships outside of Long Beach.” The company is diversifying cargoes toward Northwest and East Coast ports and plans to spend $75 million on airfreight next year, up from $8 million-$10 million this year. To compensate for higher costs, execs confirmed that Crocs will pull back on promotions and increase prices.

On Monday, during the call by Kimberly-Clark (NYSE: KMB), executives pointed to high commodity costs as well as “challenges on the supply chain side … getting the product to our customers,” including problems with global shipping. They said that transportation market issues “ripple through cost” and as a result, the company intends “to fully offset inflation with both pricing and cost reduction.”

Anchored ships as inflation bellwether

For at least some importers, particularly smaller ones paying spot rates, ocean shipping costs are a major source of import price inflation. To the extent shipping costs can be passed on, they would drive consumer price inflation for those particular imports.

“I don’t know how you can pay $20,000 to move an FEU from Southern China to North America and that cost doesn’t get reflected somewhere,” said Harvard Business School professor Willy Shih during a recent talk hosted by investment bank Evercore ISI. “We’re going to see price increases.”

But looking at inflation countrywide — inflation with a big “I” — the linkage with ocean shipping remains under debate. First, most import volume is shipped by larger players like Wal-Mart (NYSE: WMT) that pay far less than $20,000 per FEU. Second, while ocean shipping is the most heavily featured aspect of the supply chain crunch in the media, it’s just one facet of the broader transportation and storage chain, which also includes trucking and warehousing.

Third, commodity inflation may play a larger role in consumer price rises than supply chain issues, as argued by Miller. And fourth, demand may play a much larger role than supply costs. Aneta Markowska, chief economist at investment bank Jefferies, views current inflationary pressures as “largely demand-pull, rather than cost-push, which is consistent with the lack of demand destruction thus far.”

Even so, it’s a safe bet that inflation watchers will keep a sharp eye on ocean shipping, if not as a price driver then as a bellwether of what happens next. The rise in trans-Pacific spot rates and the number of ships at anchor off Los Angeles/Long Beach did coincide with rising consumer price inflation. The same correlation could hold on the way down.

“At some point port congestion will go away,” said Stifel analyst Ben Nolan. “At the moment, nothing is normal, and it does not seem to be normalizing, so 2022 looks like it will still be chaotic. Inflation here we come.”

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- Shadow inflation: Shipping costs are up way more than you think

- $22B worth of cargo is now stuck on container ships off California

- Container shipping’s ‘hockey stick’: Liner profits just keep on climbing

- How supply chain chaos and sky-high costs could last until 2023

- Shipping chaos gives top importers ‘massive competitive edge’

- Global demand isn’t booming. So why are shipping rates this high?