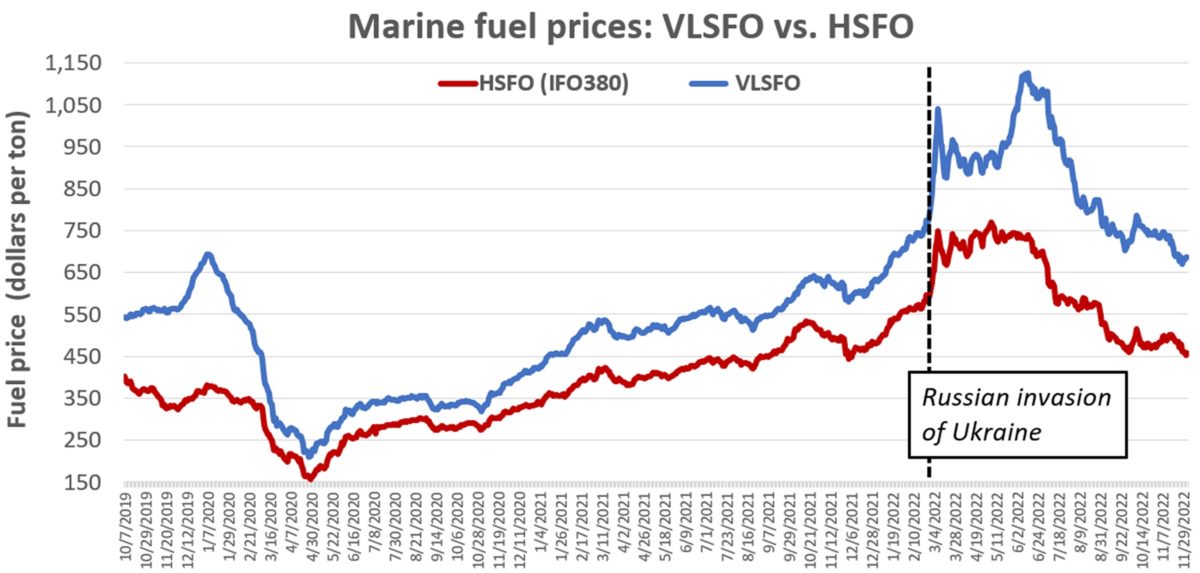

When Russia invaded Ukraine, the price of ship fuel spiked to unprecedented highs. Prices are still high in historical terms, but they’ve now fallen back to prewar levels. Ship fuel is getting cheaper as fears of future demand weakness drag down the price of oil.

Ship & Bunker put Friday’s average price of very low sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO) — the fuel used by most commercial ships — at $685.50 per ton (based on prices at the top 20 refueling hubs). That’s down 39% from the all-time high on June 14 and on par with prices seen in January.

The average price of high sulfur fuel oil (HSFO) — the fuel burned by ships using exhaust gas scrubbers — was $457 per ton, down 32% from the high on May 5 and back to levels seen in September 2021.

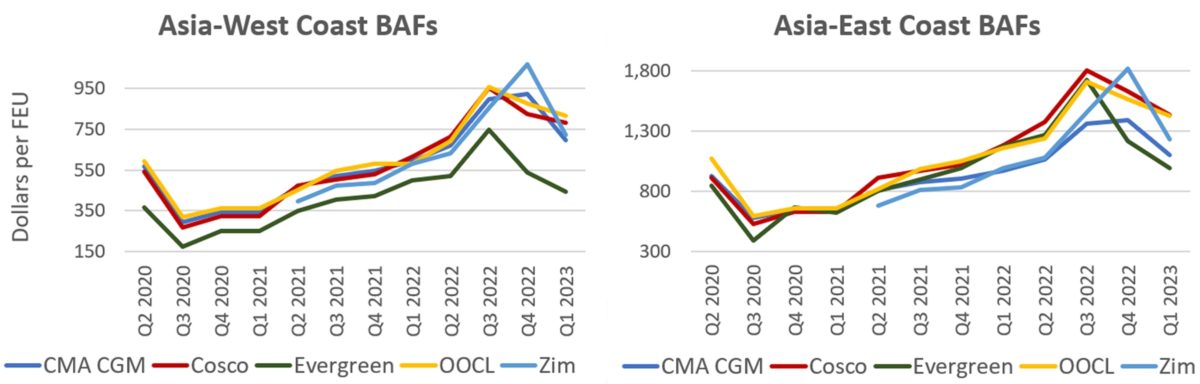

The price of ship fuel is important to importers of containerized cargo because shipping lines pass on fuel costs via bunker adjustment factors (BAFs).

In bulk commodity shipping, the price of fuel is important to spot markets because shipowners pay for fuel on spot voyages. Shipowner spot earnings are net of that cost.

Meanwhile, the VLFSO-HSFO spread is pivotal for owners of ships with scrubbers. The higher the discount of HSFO to VLSFO, the more scrubbers pay off.

Container shipping fuel surcharges falling

On Friday, DPI Signals reported container line BAFs for the first quarter of 2023. The good news for cargo shippers: BAFs are now coming down rapidly as shipping lines pass along fuel-cost savings.

The Asia-West Coast BAF of Zim (NYSE: ZIM) will be 32% lower in Q1 2023 versus Q4 2022, falling to $720 per forty-foot equivalent unit. Evergreen’s Asia-West Coast BAF peaked in Q3 2022. In the coming quarter, it will be down 41% from that high, at $443 per FEU.

In the Asia-East Coast lane, Cosco’s BAF will fall 21% between Q3 2022 and Q1 2023, to $1,425 per FEU. CMA CGM’s BAF will decline 21% between the fourth quarter and the first, to $1,098 per FEU.

Scrubber savings volatile but remain high

The spread between VLSFO and HSFO jumped to over $300 per ton in January 2020, when the new IMO 2020 regulation went into force. That regulation required ships without scrubbers to switch from HSFO to more expensive VLSFO.

But in the wake of the initial COVID lockdowns, the VLSFO-HSFO spread collapsed to around $50 per ton. This raised the question of whether scrubber installations were a mistake. A spread of around $100 per ton is generally seen as the point where scrubber installations make economic sense.

As oil pricing and refinery utilization picked up in 2021, the spread widened again. When Russia invaded Ukraine, it rocketed to new highs, surpassing the previous peak in January 2020. According to Ship & Bunker data, the average spread at the 20 top refueling hubs hit an all-time high of $420.50 per ton on July 5.

It has fallen back again in recent months. The spread was $228.50 per ton on Friday. Even so, scrubbers are still paying off handsomely for shipowners.

According to Clarksons Securities, a spot-trading, scrubber-equipped Capesize (a bulker with capacity of around 180,000 deadweight tons) earned $9,400 more per day than a nonscrubber Capesize as of Monday, due to fuel savings. Spot earnings of Capesizes with scrubbers burning HSFO were 75% higher than Capesizes without scrubbers burning VLSFO.

A 2011-built, scrubber-equipped very large crude carrier (VLCC; a tanker that carries 2 million barrels of crude) was earning $14,100 more per day than a nonscrubber VLCC in the spot market on Monday, a 26% premium.

What’s driving the spread?

American Shipper asked Stefka Wechsler, marine fuels editor at Argus, about what’s driving the spread and what could happen after the EU bans imports of Russian refined products.

“Russia exports more HSFO than VLSFO, but Russia also exports distillate fuel, which is used as a blend stock to make VLSFO,” Weschsler explained. After the war began, VLSFO prices increased in the Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp (ARA) bunkering market, while HSFO prices declined. The spread rose to historic highs in July “as a reaction to distillates availability erosion.”

The decline in the spread this autumn was due to the price of VLSFO dropping faster than the price of HSFO. Between July and November, VLSFO prices in ARA fell 25% and HSFO prices 18%, according to Argus data.

The decline in VLSFO pricing outpaced HSFO “as Northwest Europe reshuffled its VLSFO sources, importing from the U.S. Gulf Coast, Gabon, Algeria, Tunisia, the UAE and Argentina,” said Wechsler.

Asked about the EU ban on Russian products imports starting Feb. 5, he said, “Market views are divided. Some think that with Russian distillates completely out of the EU market, ARA VLSFO prices will outpace HSFO prices [widening the spread].”

“Others think the spread will narrow once all Russian HSFO stocks are depleted from the ARA,” he said. In other words, lower HSFO supply would increase HSFO prices relative to VLSFO.

Container shipping to drive future scrubber installations

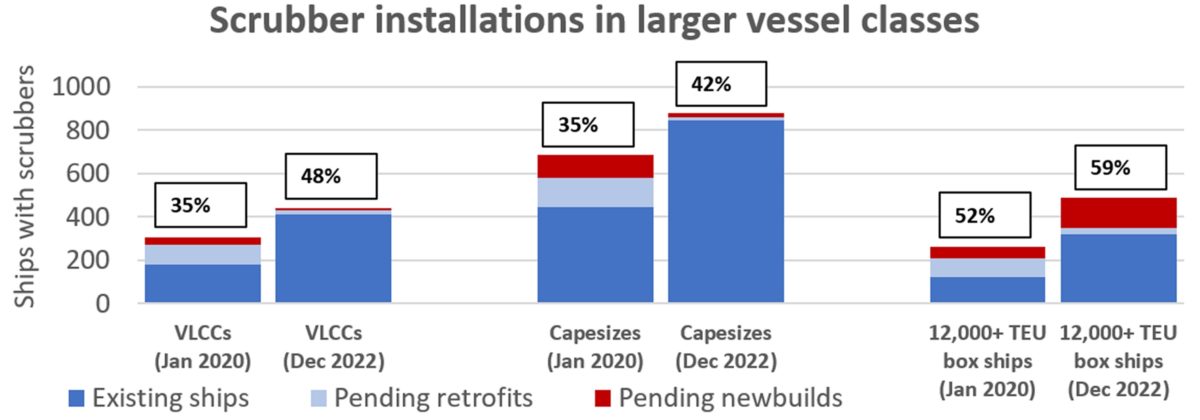

Scrubber installations make the most sense on high-capacity vessels on long-haul runs. Installations are more cost-effective with newbuildings than with retrofits.

Data from Clarksons Research shows a sharp rise in scrubber use over the past two years, but also, that most future installations will be on newbuilds, primarily on container ships.

In January 2020, when IMO 2020 was implemented, 35% of all VLCCs either on the water or on order had scrubbers installed or installations planned. As of Monday, the VLCC scrubber share had risen to 48%.

However, future VLCC scrubber installations are limited. The orderbook is extremely small, with only 27 VLCCs on order. Of those, only 26% will have scrubbers installed. Of VLCCs in service, only 19 (2% of the fleet) have scrubber retrofits planned.

The share of Capesizes with scrubbers or planned installations rose from 35% in January 2020 to 42% currently. As with VLCCs, the low orderbook will limit future installations. Only 19 of the Capesizes on order (16% of vessels under construction) will get scrubbers, and only 11 currently operating Capesizes have retrofits planned (less than 1% of the fleet), according to Clarksons Research data.

The container shipping industry has been the biggest scrubber adopter in terms of fleet share. The share of container ships with capacity of 12,000 or more twenty-foot equivalent units that have scrubbers or plan to have scrubbers increased from 52% in January 2020 to 59% currently.

Unlike VLCCs and Capesizes, newbuildings play a major role, as container shipping now has a historically large orderbook. According to Clarksons’ data, there are 140 container ships with capacity of 12,000 TEUs or more on order that will have scrubbers installed, representing 46% of ships under construction in that size category.

Click for more articles by Greg Miller

Related articles:

- The sinking price of ship fuel: Near prewar levels after summer plunge

- Ships that ‘scrub’ emissions earn twice as much as those that don’t

- Ship fuel enters uncharted territory as prices hit new wartime peak

- Ship fuel spikes to historic $1,000/ton mark as war fallout worsens

- Price of ship fuel surging, poised to eclipse all-time high

- Ship fuel price highest since 2013, ‘scrubber spread’ widens