The market for buying and selling third-party logistics providers and freight brokerages is red hot, according to Capstone Partners investment bankers Burke Smith and Nathan Feldman.

Rates for all modes of transportation rose quickly over the past year, pushing up 3PLs’ earnings power and making them more attractive targets. But buyers — especially private equity firms — are also paying more for those earnings, especially for larger brokerages, Smith said, and lenders are waiving some covenants that require companies to keep their leverage ratios at lower levels.

“Once you get above $10 million in [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization], you’re considered by the lender community to have scale and durability and that’s where you start to see very attractive lending packages,” Smith said. “There’s an inflection point there in EBITDA multiples as well. We’re seeing 7-10x for small companies … and 12-3x for companies with $20 million in EBITDA.”

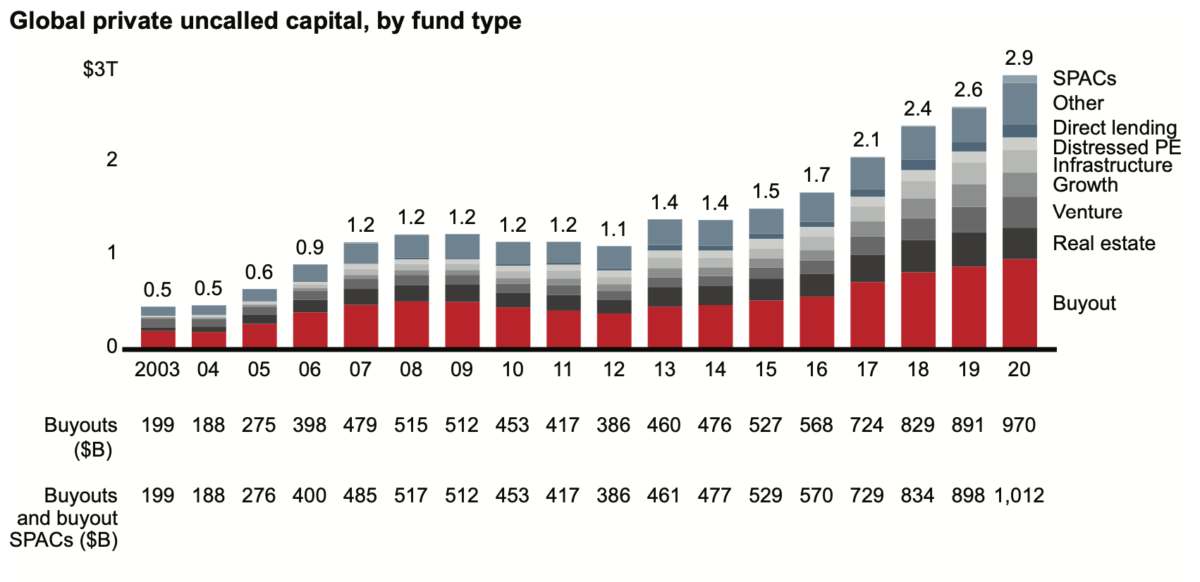

The higher prices paid for 3PL earnings and the increasing amount of debt, or leverage, put on companies are being driven by a confluence of factors. More institutional investors, including universities, insurance companies and pension funds, have funneled their capital into private equity firms, raising the PE industry’s stores of uncalled capital, or “dry powder.” The more money private equity general partners have at their disposal, the greater the pressure to put the capital to work by buying businesses.

Even as PE general partners were raising record amounts of capital, COVID-19 disrupted dealmaking, which traditionally relied on intensive business travel and in-person meetings. The economic disruptions and uncertainty that COVID introduced also constrained M&A. Target companies’ financial performance started to look anomalous and no one really knew what the future held. It was hard to close investments all through the middle of 2020.

But the result of those delays was pent-up demand for acquisitions: Capital that wasn’t deployed still needed to be invested, and deals that were not closed in 2020 had to get signed in 2021.

Finally, the behavior of freight markets themselves — especially the run-up in spot and contract trucking rates — has made 3PLs and brokerages more attractive. Higher contract and spot rates mean that brokers generate higher net revenue dollars per load, even if gross margins stay flat. The faster a target’s EBITDA grows, the easier it is to justify a higher multiple paid for last year’s EBITDA.

Last week, Echo Global Logistics (NASDAQ: ECHO) sold to private equity firm The Jordan Company for $48.25 per share, approximately $1.3 billion, or roughly 11.4x Echo’s trailing 12 months of EBITDA. Historically, non-asset domestic transportation management companies like freight brokers have sold for about 10x EBITDA, according to documents prepared by 3PL M&A advisory firm Armstrong & Associates. Jordan’s bid represented a 54% premium to where Echo’s shares were trading prior to the announcement.

“The Echo deal is further confirmation that private equity competition for logistics assets is white hot,” Smith said. “There is a pretty severe disconnect between how public company shareholders value brokerage earnings and where private equity investors see value. The Jordan Company is a smart and experienced logistics investor – they reportedly made a quick double on their 2018 investment in GlobalTranz after just eight months. Their willingness to place a premium value on ECHO at this late stage in the freight bull market is encouraging. It suggests that they see continued healthy markets in the near-to-medium term.”

Smith and Feldman advised freight brokerage Everest Transportation Systems on its sale to Cambridge Capital last week. Everest is notable because the large majority of its operational staff are in Kiev, though the company is headquartered in Evanston, Illinois. Everest’s model leverages an inexpensive workforce that has language skills helpful for communicating with Eastern European small carriers and owner-operators in the Midwest. Everest’s strategy of offshoring talent, but managing it in-house rather than through a staffing firm, has an even more pronounced impact on operating expenses, Smith said.

“The Everest deal was fascinating to work on right now,” Feldman said. “I’ve never seen a stronger seller’s market for M&A before. It was great to see the interest in Everest too — those guys have built a great mousetrap.”

Everest’s unique operating model was key to catching the attention of buyers who need help justifying high entry points. Smith said that technology trends like digital freight brokerage and transportation management, hybrid models in which 3PLs own some assets and 3PLs that aggressively implement offshoring or nearshoring strategies have attracted attention from buyers who know they will have to pay up for a 3PL in the current M&A market.

“What we see in the market, broadly speaking, is that 3PLs are trying to figure out how to move forward year by year and stay competitive,” Smith said.

Continued innovation in the 3PL industry has stabilized some of the more violent cyclicality that historically plagued transportation companies’ earnings, Smith said, and savvy private buyers know how to identify resilient brokerages. One strategy used by private equity firms to lower their entry points in expensive, ‘platform quality’ freight brokerages is to “buy and build”, or tack-on smaller subsequent acquisitions at a lower multiple.

“Distinguishing between revenue growth and volume growth, for example, is part of every conversation and part of every process,” Smith explained. “We are steeped enough in brokerage at this point that we’re good at explaining the dynamic. If you look at the history of C.H. Robinson and Echo, how those companies performed long term through cycles has been pretty compelling. Cash flows don’t crater in down markets. Things get tighter, but people find ways to cut costs and survive and thrive through up and down markets.”

Smith said that persistently low inventory levels in the United States suggest that demand for transportation services will stay hot for the foreseeable future. The only thing he could see that would materially slow the pace of M&A, he said, would be a hypothetical dislocation on the lender side of the market that drove interest rates up and made leveraged buyouts more difficult. As long as transportation companies are doing well, prices for them should stay strong.

“I see at least a year of really strong transportation supply and demand dynamics for service providers,” Smith said, underscoring his belief that underlying freight markets will remain favorable for transportation providers.