Americans were quite surprised when they first heard the news reports on April 18,1961, that a fleet of ships arrived in Cuba’s Cochinos Bay to deliver an invasion force intent on removing communist leader Fidel Castro from power.

The invasion proved to be a disaster, with most of the anti-Castro forces either killed or captured in the first hours. In retrospect, the intelligence, planning, support, purpose, training and equipping of the invaders were woefully inadequate.

The site chosen for the invasion on the south coast of Cuba, about 75 miles southeast of Havana, was named Cochinos Bay, better known as the “Bay of Pigs” due to aggressive pigs found in the area. Although an airport and highway linked to Havana were nearby, the surrounding terrain was swampy and difficult to navigate on foot.

Unlike the Normandy invasion during World War II or the landing at Inchon during the Korean War, this was to be a stealthy, nighttime operation by U.S.-trained anti-Castro guerillas. It was expected the local population would support and join with the invasion force to topple the communist regime.

From the start, the Bay of Pigs was not an ideal location for this type of assault. There were no docks or wharfs to tie up the ships. Submerged coral reefs made navigation and landings difficult, while the depth of the water in the bay – more than 800 feet deep in some places – made anchoring the ships prohibitive.

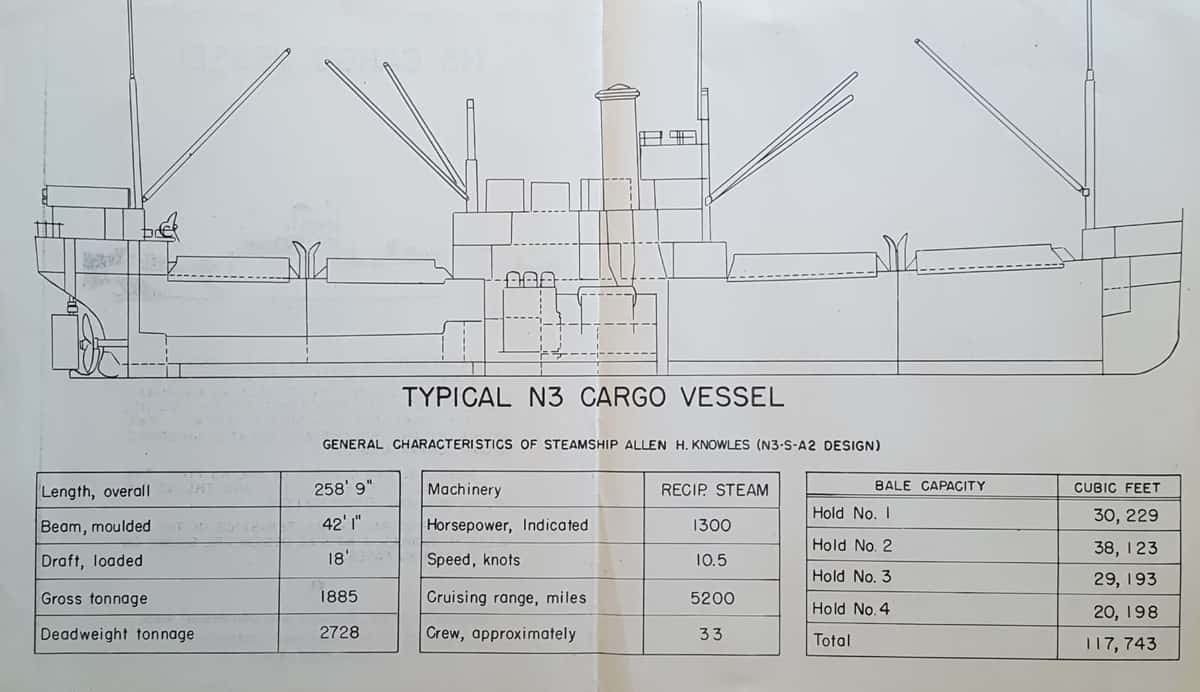

The invasion fleet consisted of World War II-built vessels, most of which were approaching 20 years old at the time. The largest group were five U.S.-designed and built N-3 type ships.

During World War II, U.S. coastal shipyards were overworked with the repair and construction of large merchant and naval ships. It became necessary to build numerous smaller vessels at inland and Great Lakes yards. As a result, about 30% of the 109 N-3 ships originated from three Great Lakes yards.

The purpose of the N-3 was to replace the many coastal British vessels that were lost to the German Navy and Air Force early in the war.

Since coal was plentiful in Britain at the time, the first 36 ships were fitted with coal-fired boilers, while the remainder burned oil. Each vessel measured just under 259 feet in length with a 42-foot beam. The ships averaged 2,800 deadweight tons and their 1,300-horsepower engines could propel them at 11 knots.

Initially, the N-3s were named after captains of famous American Clipper ships, although a few were launched with a “Northern” prefix to their names.

The N-3s served gallantly in all theatres of the war. When peace returned, the ships found employment in either the Baltic, Caribbean or Far East merchant trades. By 1949, 18 flew the flag of the China Merchants Steam Navigation Co., while a number still remained in the U.S. National Defense Reserve Fleet.

The five N-3 ships used during the Bay of Pigs invasion included the Atlantico, Caribe, Houston, Lake Charles and Santa Ana. All served as transports, ferrying supplies, ammunition and vehicles for the anti-Castro guerillas. Four N-3s survived the invasion. The Houston was bombed and burned before foundering on the Cuban shoreline.

The invasion’s command ships consisted of two LCIs (landing craft infantry), named Barbara J. and Blagar. They were 158 feet in length and carried about 200 soldiers each. Ten U.S. shipyards produced 923 of these craft during World War II. Affectionately known as the “waterbug navy,” these craft were twin-screw, diesel-powered, very maneuverable, and could do 14 knots. The Blagar was sunk on April 17,1961, but the Barbara J continued a commercial career after the invasion.

Another ship used for the Bay of Pigs invasion was the Rio Escondido. It was built in Britain as an LCT (landing craft tank) in 1945 and converted to a cargo ship. It was purchased by the Suwanee Steamship Co. in 1959 and flew the Liberian flag. Fully loaded with cargo during the invasion, it was bombed and sunk by Castro’s air force.

Other minor vessels in the invasion force were three LOUs (limited official use), three LCUs (landing craft utility), and four LCVPs (landing craft vehicle and personnel), as well as numerous other non-descript vessels.

One of the N-3s, the Santa Ana, was deployed off Oriente Province as a diversionary landing force but ultimately broke away from the invasion.

Meanwhile, 25 miles offshore and out of sight, 22 U.S. Navy ships monitored the invasion’s progress, including 12 destroyers, a submarine, and the aircraft carriers Boxer and Essex. They abandoned the scene once the invasion force floundered.

For maritime historians, the Bay of Pigs invasion has become known as the world’s most disastrous amphibious operation.

Click for more Maritime History Notes articles by Capt. James McNamara.