The benchmark price used as the basis for most fuel surcharges continued to barrel ahead Monday, even as the strong upward trend in diesel futures and wholesale prices has taken a breather for at least a few days.

The Department of Energy/Energy Information Administration price rose 13.9 cents a gallon to $4.378. It’s the highest level since Feb. 21. With gains in the price in five of the past six weeks, and that sixth week recording no change in the price, the DOE/EIA diesel price is up 36.1 cents a gallon since July 3.

Coincidentally, July 3 is the date of the most recent market low in the price of ultra low sulfur diesel on the CME commodity exchange.

It settled that day at $2.3773 a gallon. It then set off on a run of 17 daily increases out of the next 21 days. Recent gains took the price of ULSD on the CME to a high settlement of $3.207 a gallon Wednesday, but it has since slid back to a settlement of $3.0883 Monday, for an overall gain of about 71 cents since the July 3 low.

With that gain in futures prices, wholesale prices generally move up at a high correlation. But even with the increases in retail prices as evidenced in the DOE/EIA price, the price at the pump continues to lag gains in wholesale and futures markets by a large margin.

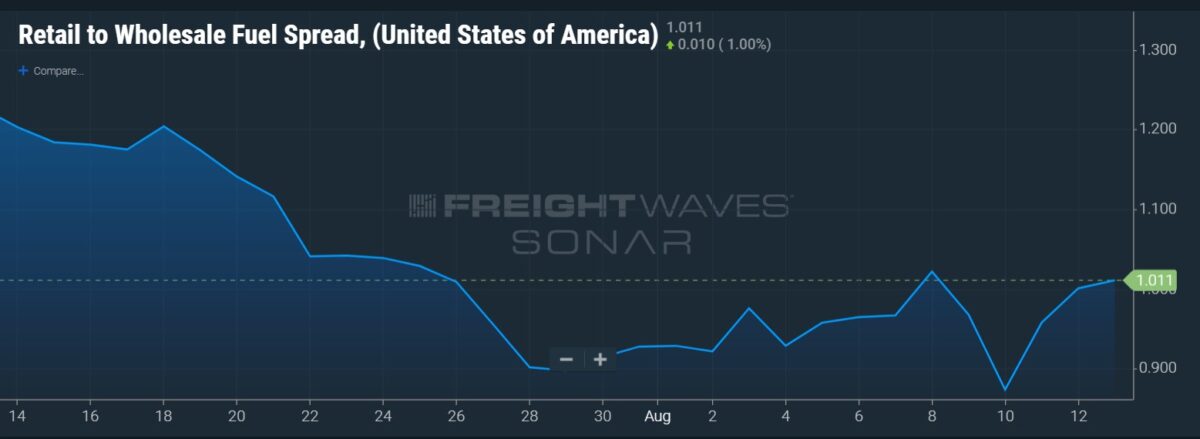

That is most apparent in the FUELS.USA spread in FreightWaves’ SONAR. It stood at $1.204 a gallon on July 18 before plunging to 87.4 cents a gallon on Thursday, as retailers failed to keep up with the blistering pace of increases in the wholesale and futures markets. With the cooling of those latter markets the past few days, and with retailers continuing to put through increases to reflect the earlier higher prices, the national spread in FUELS.USA increased to $1.011 a gallon on Sunday.

The surge in oil markets in general has been driven by a tightening supply/demand balance that the International Energy Agency spelled out in its August report last week.

What has been particularly notable on top of that is that diesel prices have surged at a rate far higher than that of crude, propelled in part by tight inventories around the world. The price of ULSD on the futures market moved to a premium of more than $40 a barrel toward the end of July and the first days of August, the first time at that spread since the days leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In his weekly report, energy economist Philip Verleger, who has long focused on diesel as a more impactful driver of oil prices than it generally gets credit for, reached back to a magazine article from 1986 that highlighted a sign in a major oil company office. The sign said KILL, and it stood for “Keep Inventories Low and Lean.”

Looking at the current market, Verleger wrote, “KILL is back with a vengeance.”

“Inventories are low in 2023 for the same reason they were low in 1996,” Verleger wrote, citing another year of tight inventories and rising prices. “Markets are in backwardation. With backwardation, the customers of refiners — marketers — will do everything they can to limit their stocks.”

(Below is an example of a New York Times headline from that period.)

Backwardation is a market condition in which the price of a commodity for future delivery is lower as the calendar moves forward. The ULSD settlement Monday was $3.0883 a gallon for ULSD delivered in New York Harbor in September. The price for October settled at $3.0682 a gallon.

Because prices with a further-out delivery date are lower than the current price in a market backwardation, it discourages building inventories. As soon as a barrel available today is put in inventory, its value declines in a market backwardation.

The backwardation in diesel has gotten particularly severe in recent days. Looking at the spread between front-month ULSD and the price 12 months out, on July 3 it settled at a 4.51-cent spread. However, as diesel inventories tightened, that spread started to blow out, reaching a whopping 49.07 cents a gallon Wednesday.

But in the same way that the front-month price of ULSD has dropped the past few days, so has the spread between front-month and 12-month ULSD. It settled Friday at 15.66 cents a gallon and was slightly wider Monday at 18.21 cents.

How does that end? If a backwardation discourages inventory building, how does a market ever build the stocks it needs?

It generally happens when refiners can make such huge margins on making diesel that they end up producing more of it than the market needs, and backwardation or not, the fuel ends up in storage.

But Verleger’s report doesn’t see that happening anytime soon. He notes that refining in the U.S. has moved away from integrated companies with the spinoff of refining units over the years by ConocoPhillips and Marathon Oil, creating new independent refiners. “The market’s altered structure, where the major refiners are independent of supermajors such as ExxonMobil and Shell and the marketers and distributors are equally independent, creates a situation where everyone has good reason to minimize inventories absent futures market signals to build stocks.” And those signals are pointing the other way at present.

Another factor in the surge in diesel prices: Wall Street investors have decided they think diesel is a good investment.

Reuters chief energy correspondent John Kemp, reviewing data from the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission, said fund managers have bought more diesel futures position than they sold in 12 of the past 14 weeks.

“[Diesel] inventories have failed to rebound significantly from their cyclical lows in the middle of 2022, and there is not enough spare refining capacity to boost them readily,” Kemp wrote Monday. “As a result, traders increasingly expect that a soft landing for the U.S. economy and resurgence of manufacturing and freight activity will quickly lead to diesel shortages re-emerging.”

More articles by John Kingston

How 1 city is curbing overweight trucks

1st peek at Pilot’s finances after Berkshire Hathaway ownership grows

After declines and revisions, US truck jobs now below October 2022 level