Air cargo has seen its share of issues this year – softening traffic and yields, global economic growth slowdown concerns, trade wars and tariff threats adversely impacting business confidence, and economic indicators domestically pointing to a slowdown – plus the trucking industry is in what looks like a freight recession in the U.S. The current uncertainty on when the grounded Boeing 737 MAX fleet will be back into the air is potentially another pressure point for air cargo.

Late last week, American Airlines announced its fourth delay to its service resumption date for its Boeing 737 MAX aircraft. Southwest, the largest operator of 737 MAX aircraft in the U.S., and United Airlines have also pushed their service resumption dates back until mid-fall. Additionally, the Wall Street Journal reported on July 13 that the aircraft may not be approved to return to service until early 2020. While each airline clearly cites major passenger revenue losses from the delay, is there much cargo impact?

As a narrow-body airplane, the 737 MAX and other Boeing and Airbus aircraft of similar size carry only a limited portion of the cargo that needs to fly by air. This portion includes smaller weight air waybills with lower piece weights and more compact dimensions that are able to be manually loaded through the smaller, narrow-body cargo door. What fits typically includes mail, express packages, smaller e-commerce consignments, non-skidded perishables (flowers, seafood, produce), pets, human remains and other carton-size traffic.

Low flight loads

As a result, U.S. Department of Transportation T-100 data shows MAX-size aircraft on U.S. domestic flights averaging only 250-500 pounds of air freight per flight, or load factors of 20 percent or less. Depending on baggage loads and other factors, these aircraft normally have the space and weight to handle 1,500-3,000 pounds on a domestic flight, and sometimes more. In fact, some high-demand export markets in Central and South America have high volumes of flowers and perishables that can maximize the space on narrow-body aircraft.

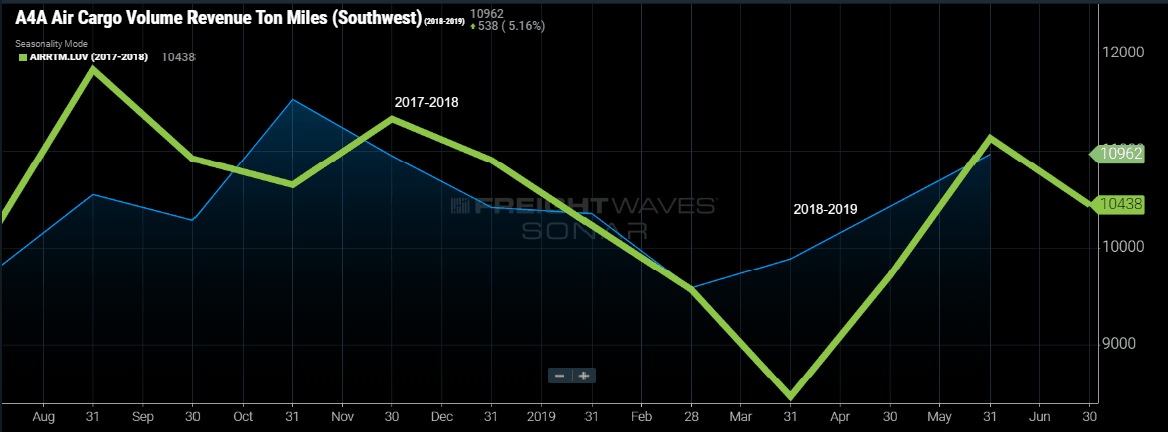

FreightWaves’ analysis of the latest monthly government transportation data shows that in early 2019, just prior to the March grounding, the MAX carried just under 1.0 percent of American Airlines’ U.S. domestic cargo, 5.1 percent of Southwest Airlines’ domestic cargo, and 1.1 percent of United’s. With such modest loads, other replacement flights can easily carry any displaced MAX cargo. In fact, Southwest saw its April 2019 domestic tonnage increase 6 percent over March and exceed April 2018, after the MAX was grounded, and as seen in the SONAR chart below (AIRRTM.LUV). Loads on its non-MAX 737s increased 15-20 pounds per flight. Delta Air Lines, which doesn’t have any 737 MAX aircraft in its fleet – and might have been expected to benefit from its competitors’ groundings – saw 7.4 percent less domestic cargo in April than March. For American, Delta and United the limited domestic wide-bodies they operate offer far more space and flexibility for customers, and therefore carry a larger part of their domestic cargo tonnage, averaging between 8,000 and 12,000 pounds per domestic flight.

Airline industry feedback

Wally Devereaux, Managing Director at Southwest Cargo, the largest U.S. operator of 737 MAX aircraft, confirmed that Southwest is not seeing a major impact on the Cargo division. He noted, “As a whole, the Boeing 737 MAX 8 represented about 5 percent of our 4,000 daily departures. Even with the MAX 8 grounded, we have still been able to offer many different routing options to our cargo customers through our high frequency, point-to-point flight schedule, that meet their overall needs.” An American Airlines Cargo spokesperson also confirmed the grounding is resulting in little to no impact on its cargo operations. United Airlines, with the smallest MAX fleet of these U.S. airlines, did not comment.

For Air Canada, which operated 24 MAX aircraft, the grounding affects a significant part of the fleet. But according to Tim Strauss, Vice President of Cargo for Air Canada, the impact of the grounding on cargo has been mixed. Strauss told FreightWaves, “The substitute fleet we put up actually increased our cargo capacity by 1 percent as, in some cases, we substituted wide-body lift for the narrow-body MAX. [That is] Probably the only ‘plus’ to be found. On the other side of the coin, we lost a few frequencies – some markets that were served five times a day with a MAX are now being served with the same number of seats but with maybe four flights [instead of five]. This timing impact may or may not affect routing decisions by traffic managers and is absolutely impossible to measure.”

Overall, North American carriers indicate they are managing the grounding issue with little impact on cargo. But the impact could slowly grow the longer the aircraft is out of service and as summer passes into the peak fourth quarter shipping season, when load levels typically pick up. To this point, only a limited number of shippers are squeezed by fewer narrow-body flight choices in the schedule and the loss of opportunity on deferred new routes that were originally planned with the MAX aircraft in service. Still, as overall MAX and other narrow-body flight loads are low, most MAX cargo for North American airlines can be re-accommodated on remaining flights.