To gain insight into the shifting landscape of freight brokerage, sometimes it’s best to follow the money, not the shiny new technology.

The freight brokerage industry is undergoing a wave of rapid transformation. Incumbent asset-based carriers are aggressively growing their logistics offerings in pursuit of counter-cyclical margin and new digital entrants are redefining the upper limits of automation and broker productivity. But perhaps the most significant recent development – vast amounts of private capital deployed to consolidate the third-party logistics (3PL) industry – has been under-reported and is less well understood.

In a fragmented industry like freight brokerage, mergers and acquisitions (M&A) will always be an attractive route to gain scale, but during the past few years, competition among buyers has intensified. Private equity (PE) groups have bid up freight brokerage EBITDA multiples to low to mid double-digits (12-14x), making it hard for strategic buyers, i.e. other logistics companies, to close deals.

Inflated asset prices in the 3PL space are the result of a chain of events, beginning with institutional investors like pension funds and university endowments looking for alternative investments that generate higher returns than publicly traded stocks. Investors have piled into private equity, driving stores of uncalled capital (known as dry powder) to record levels. That money must be put to work in a finite universe of acquirable companies, driving up multiples.

It’s still very much a seller’s market when it comes to high growth freight brokerages. I spoke to one brokerage CEO in May who said he had been approached, unsolicited, by a top venture/growth equity firm that wanted to make an investment. Happy with his current investors, the executive said that he would only consider a capital infusion – and this firm writes $20 million to $100 million checks – if it came with no covenant, no board control and very little dilution.

M&A activity could accelerate even further after freight markets bottom and begin their recovery, according to Andrew Clarke, the former chief financial officer at C.H. Robinson (NASDAQ: CHRW).

“You have the different themes of consolidation, and it happens at different points in the economic cycle,” Clarke said on-stage last month at FreightWaves’ Transparency19. “It doesn’t happen at the most powerful points in the economic cycle; usually it’s after you’ve bounced off the bottom and companies start seeing recovery and you start seeing consolidation.”

As private equity grew more crowded and bid multiples went up, returns naturally suffered. In theory, as a PE group pays more to acquire a company, it limits its potential upside. But there is no sign that private investment in asset-light brokerages is slowing down, and PE firms have developed strategies to generate returns even in a period of high multiples.

Bain & Co.’s Global Private Equity Report 2019 outlines how PE firms can afford to pay high prices for companies and still capture solid returns upon exit.

“A growing number of [general partners] are facing down rising deal multiples by using buy-and-build strategies as a form of multiple arbitrage – essentially scaling up valuable new companies by acquiring smaller, cheaper ones,” Bain’s analysts wrote.

In other words, a PE group will pay more for a “platform-quality” 3PL – one that has advanced technology, for instance – and then average down its entry multiple over time by adding on smaller brokerages at lower multiples. Those subsequent acquisitions of mid-sized companies that should benefit from the acquirer’s technology might be made at multiples from 6-8x EBIT.

“A buy-and-build strategy allows a general partner to justify the initial acquisition of a relatively expensive platform company by offering the opportunity to tuck in smaller add-ons that can be acquired for lower multiples later on,” Bain wrote. “This multiple arbitrage brings down the firm’s average cost of acquisition, while putting capital to work and building additional asset value through scale and scope.”

Bain defines ‘buy-and-build’ as “an explicit strategy for building value by using a well-positioned platform company to make at least four sequential add-on acquisitions of smaller companies.”

In the 3PL space, GlobalTranz is the poster child of the private equity-backed roll-up strategy, having completed nine acquisitions since the beginning of 2017. This past April, The Jordan Company sold GlobalTranz back to Providence Equity Partners after a holding period of just eight months, during which GlobalTranz was able to double EBITDA. Buying back its agents’ franchises was likely the major contributor to GlobalTranz’s earnings growth, but acquisitions certainly played a role as well.

It’s not just GlobalTranz, though. According to Transport Topics, of the top 25 freight brokerage firms in 2019, 12 are privately held. The others – companies like Echo Global Logistics, Coyote Logistics or J.B. Hunt Integrated Capacity Solutions – are either publicly traded or are owned by a public company. The 12 private brokerages are Allen Lund, BlueGrace Logistics, England Logistics, FLS Transportation, GlobalTranz, Mode Transportation, Nolan Transportation Group, Redwood Logistics, SunteckTTS, TQL, Trinity Logistics and Worldwide Express.

Eight of those 12 are backed by private equity; only Allen Lund, England and Trinity are still founder- or family-owned, and Trinity just completed a merger with Burris Logistics, another Maryland-based logistics major. The PE-backed brokerages are fairly large businesses – the smallest, FLS Transportation Services, reported $500 million in gross revenue and $75 million in net revenue in 2018, according to Transport Topics. The PE-backed brokerages are large, growing rapidly and jockeying for position.

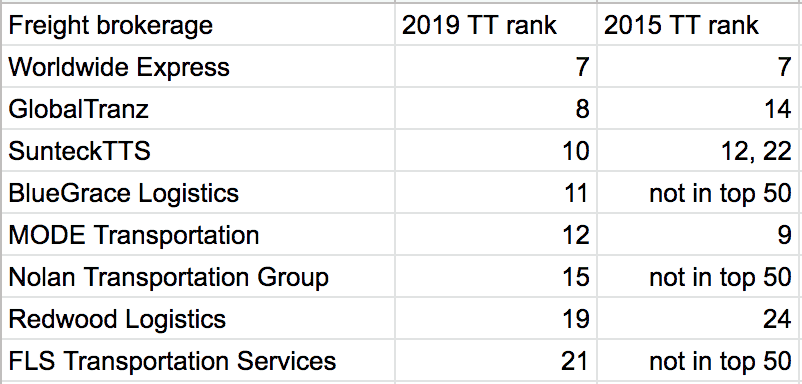

The table below compares PE-backed freight brokerages’ rankings on Transport Topics’ 2019 list versus their rankings on the 2015 list:

Note that SunteckTTS was the product of a merger between Sunteck and TTS that closed in January 2017; the two 2015 rankings are for Sunteck and TTS, respectively. MODE Transportation is the only brokerage on the list whose ranking dropped, but MODE has only been backed by private equity for about nine months. York Capital Management acquired MODE from publicly traded Hub Group in September 2018 for $238.5 million; expect acquisitions and accelerated growth from MODE over the course of York’s holding period.

Strikingly, three of the top 25 freight brokerages were not even in the top 50 four years prior, and each of those are owned by private equity – BlueGrace, FLS Transportation and Nolan Transportation Group (NTG).

BlueGrace Logistics, the Tampa-area brokerage founded in 2009 by Bobby Harris, only recently stomped on the accelerator. In August 2016, Warburg Pincus poured $255 million of growth equity into BlueGrace, which has since grown its headcount above 500 employees, according to Pitchbook.

“Over the next two years, we’ll go well over 500 employees, and in the next three to five years have about 1,000 employees just here in Tampa,” Harris told the Tampa Bay Times at the time of the deal.

NTG, founded in Atlanta in 2005, received its first private equity backing in September 2016 in the form of $24.5 million of development capital from Ridgemont Equity Partners. That year, NTG posted gross revenues of $196.3 million, according to its Inc. 5000 listing; just two years later, in 2018, revenue quadrupled to $811 million.

Capital fuels growth, and growth attracts more capital. In September 2018, private equity group Gryphon Investors bought Transportation Insight, a brokerage and managed transportation platform company with its own transportation management system. Sellers in the deal included Ridgemont Equity Partners, which had invested an undisclosed amount in Transportation Insight in December 2014 supported by $15.8 million in senior debt.

Just three months later, in December, Transportation Insight, now sponsored by Gryphon, purchased NTG from Ridgemont. Expect further acquisitions and fast growth from Nolan Transportation Group over the next few years – if Gryphon follows the standard private equity playbook, it will attempt to roughly double NTG in size.

Finally, Montreal-based FLS Transportation Services, Canada’s largest brokerage, took on an undisclosed amount of growth equity in February 2016 from Abry Partners, a Boston-based private equity firm with $12 billion in assets under management. That year, FLS pulled in an estimated $260 million in gross revenues, which means the brokerage roughly doubled its revenue from 2016 to 2019. A big part of that growth was the FLS acquisition of Georgia-based Scott Logistics in February 2019, a $155 million revenue freight brokerage. Abry and FLS are actively hunting for more deals, FLS chief executive officer John Leach said at the time of that acquisition.

Even beyond the top 25 largest brokerages, private equity has fueled consolidation and high growth. ReTrans, acquired by Tailwind Capital in 2012, was sold to Kuehne + Nagel in 2015 for $190 million. Magnate Worldwide, at $198 million in gross revenue for 2018, was founded by Magnate Capital Partners and CIVC Partners in January 2015. Buoyed by more than $100 million in debt issuances, Magnate acquired Masterpiece International in 2017 and Domek Logistics in November 2018.

In many industries consolidated by private equity, one risk is that the space will ‘barbell,’ or become lopsided in such a way that only small companies and large companies are left, with the middle market hollowed out. Given the high number of $100 million revenue freight brokerages and the relative ease with which a $50 million brokerage can reach that threshold, it appears that the 3PL space is in no danger of barbelling in the foreseeable future.

FreightWaves expects private equity to be a major force in building larger freight brokerages for at least the next five to seven years.