Go ahead, whack your tires. Are they properly inflated? Do you really know?

Al Cohn, director of new market development and engineering support for Pressure Systems International (P.S.I.), says that the historical manual method of checking tire inflation is no longer sufficient if you want to run the most fuel-efficient operation possible. To be fair, it’s in Cohn’s best interest to promote automatic tire inflation systems as the best method to achieving fuel efficiency, as that is what P.S.I. has been known for over its 25 years of existence, but if you listen to Cohn lay out his case, you can’t help but wonder why drivers continue to hit tires.

During a presentation at the Meritor/P.S.I. Fleet Technology Event in San Antonio last week, Cohn noted that tires continue to be the number-one maintenance cost for fleets. If thumping a tire truly worked, that wouldn’t be the case. And that cost is expected to rise as tire prices are heading upward in 2019 due to a rubber shortage. Cohn said he expects price increases of 5% to 7% for most brands, and that is on top of increases this year.

To illustrate the rising costs of new tires, Cohn visited a truck stop in Canton, OH, and did some price comparison. In 2017, 2 Kelly LHS steer tires cost $710.64; 8 Kelly KDA drive tires were $2,921.76 and 8 Kelly LHT trailer tires were $2,601.76 for a total of $6,234.16 before mounting, alignment and installation charges were applied. Those exact same tires in 2018 cost $748.46, $2,993.84, and $2,673.84 for a total of $7,968.41, mounted and installed. Tack on another $400 or so in 2019, assuming a 5% price increase, and you have a significant investment.

With so much money invested in tires, Cohn said that maintaining proper inflation pressure is the key to reducing maintenance costs, improving fuel economy, and avoiding road gators. “Ninety percent of the time it’s due to running a tire [underinflated] and it’s going to fail,” he said.

Tires losing air is a natural phenomenon (they naturally lose between 1 and 3 psi per month statically, Cohn said, and up to 5 psi dynamically), but they can also lose air due to tread punctures, sidewall damage and leaking valve cores or stems. The valve core has a 4 in. pound spec that many fleets are not even aware of.

“There is a tool that is about $35 [to ensure this meets specs], it’s the best investment you can make,” Cohn said.

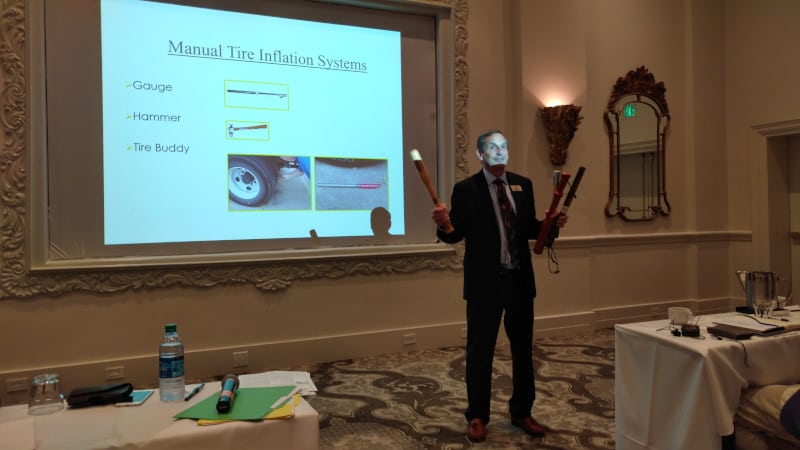

One of the leading causes of tires running underinflated is due to drivers using “manual” methods of checking inflation. Walk into any truck stop and you will find tire thumpers, but they are not accurate, Cohn said.

“Unless the tire is flat, you can’t tell the whether the tire is at 70 or 80 or 90 psi,” he said, pointing out that you might be able to hear a different sound between tires, but that only indicates the tires are not at the same psi, neither of which may be the correct psi.

Many drivers use gauges, which helps, but even gauges don’t provide a truly accurate reading. Gauges are plus/minus 3 psi out of the box, meaning your tire could be at 100 psi or 97 or 103. An underinflated tire leads to several problems.

“If the tire is not running smooth and even, you’re fuel economy goes down and it’s [quicker] to miles to removal,” Cohn said. Uninflated tires also lead to more punctures due to the larger footprint of the tire, irregular wear, and more heat in the tires, which also speeds wear.

What does an underinflated tire look like? Cohn said it leads to a larger footprint with a tire at 100 psi producing a footprint of 7 inches in length. That increases as the psi goes down and a tire at 70 psi produces an 8 ¼ inch footprint – 18% more. That 18% larger footprint produces a 3.5% negative impact to fuel economy, Cohn noted. If you run a wide-base tire, it produces 25% more footprint at a psi of 70 versus one of 120.

Automatic tire inflation systems, like P.S.I.’s, can ensure that a tire remains properly inflated until it can be repaired. The systems, which allow the user to set proper tire inflation pressure, are not a substitute for checking tire pressure, but are a hedge against an underinflated tire, allowing time to get it repaired or replaced without leading to truck downtime.

How much will an ATIS system save? According to Velociti, which retrofits the Meritor MTIS (made by P.S.I.) for fleets, the system saves on fuel costs, tread wear, maintenance and downtime. The company estimates an average annual cost savings per trailer of $2,235 ($700 due to tire downtime/replacement; $775 due to fuel savings; $480 in maintenance; and $280 for treadwear savings).

Cohn noted that there is no proper tire pressure. He recommends fleets review the Tire & Rim Association’s tire pressure book which cross references loaded weight and pressure tables for each type of tire. He also advised paying attention to which type of tire you purchase. There are 768 tires and retreads that are SmartWay certified, Cohn said, and they all produce varying levels of rolling resistance.

“Just because you buy a tire for fuel economy and it’s on the SmartWay list doesn’t mean you are going to get the same result,” he noted.

Tires may all look the same, but their tread compounds and construction play an important role in how they perform and how much they cost. Even the best tires, though, are no match for underinflation.

Adam

Please check your receipt for the Kelly tires out of Canton, OH. New price you have for $7968 is really only $6416. With the 5% increase, you would be looking at $300 vs your $400

Steve

I’ve always thumped tires, not to check pressure, that’s done at the beginning of my day, but a quick check for flats during the day. It also kept me alert during the day for a quick jump out of the truck and walk around hitting tires. I have over the 30 years or so I ran duels found a tire 30 lbs or so low. Also I’ve gauged tires I thought were low, that weren’t low. Now with my NGWS I use a temperature gun and shoot all my tires looking for an elevated tire temperature which is more accurate finding low tires. Even with a TPMS I’ve found inaccurate pressures. One always needs to manually gauge tires, it’s the old tried and true method that continues to be reliable for me.