The National Transportation Safety Board has determined inaccurate stability calculations led to the September 2019 capsizing of the Golden Ray in Georgia’s St. Simons Sound.

“The NTSB determined the probable cause of the capsizing of the Golden Ray was the chief officer’s error entering ballast quantities into the stability calculation program, which led to his incorrect determination of the vessel’s stability and resulted in the Golden Ray having an insufficient righting arm to counteract the forces developed during a turn while transiting outbound from the Port of Brunswick through St. Simons Sound,” the marine accident report released Tuesday said.

According to the report, the vessel’s operator, G-Marine Service Co. Ltd., contributed to the accident because of a “lack of effective procedures” in its safety management system for verifying stability calculations. The 2017-built Golden Ray was chartered by Hyundai Glovis Co. Ltd. of South Korea.

“The NTSB concluded the Golden Ray did not meet international stability standards at departure and possessed less stability than the chief officer calculated,” the report said.

A section on the principles of stability on Page 31 of the 57-page report explained that “a vessel that is floating upright in still water will list, or heel over to an angle, when an off-center force is applied.”

Golden Ray ‘could have capsized on a previous voyage’

The report said the ship’s master had joined the crew in Freeport, Texas, only 11 days before the accident. He had not sailed on the Golden Ray before. The chief officer, the second in command, had served on the Golden Ray for six months.

Prior to berthing at the Port of Brunswick, the Golden Ray called ports in Veracruz and Altamira, Mexico, Freeport, and Jacksonville, Florida.

“In the days before the Golden Ray arrived at each port, the charterer sent the chief officer a preload plan specific to the upcoming port,” the NTSB report said. “Once the chief officer received a preload plan, he reviewed it and used the estimated weight and locations of the cargo being loaded and offloaded to determine whether the vessel would meet stability requirements with the changes in position and weight of the cargo.

“According to company procedures, if the chief officer did not believe that the vessel could safely accommodate the cargo and meet required vessel stability, he would coordinate with the charterer to determine how to adjust the preload plan to meet the stability requirements. The chief officer did not object to any of the preload plans for the Port of Brunswick or the four ports before,” it said.

For the Brunswick call, Hyundai Glovis emailed a preload plan to the Golden Ray’s master and chief officer about 30 hours before the vessel was scheduled to arrive at the port. The plan called for 265 Kia and Hyundai vehicles to be offloaded and 362 Kia SUVs to be onloaded.

According to the NTSB, the chief officer said he only received the number and type of vehicles but not the weight, but a postaccident review “confirmed that the plan contained the number of vehicles and the total weight to be loaded in each loading location.”

The master is required “to be satisfied that the ship has sufficient stability at all times,” but the NTSB said he did not review the chief officer’s calculations. He also did not generate a departure report that is to include calculated metacentric height and draft.

An analysis determined at the time of the capsizing, the Golden Ray’s metacentric height was 5.8 feet, below the required 8.3 feet and the chief officer’s reported 8 feet.

Additionally, the Golden Ray “had over 40% less ballast, fuels and freshwater (liquid loads) in its tanks as well as 12% more cargo weight than … benchmark conditions,” the NTSB said.

Further, the analysis concluded the ro-ro carrier “as loaded had an extremely low righting energy, which prevented it from withstanding further adverse static or dynamic heeling effects and enabled the vessel to capsize due to the centrifugal force experienced by the vessel throughout the starboard turn.”

Analyses of the Golden Ray’s voyages to Jacksonville and Brunswick showed the chief officer’s calculations also were wrong, the NTSB said, and the car carrier “could have capsized on a previous voyage if it had been exposed to more severe adverse conditions.”

The chief officer declined to be interviewed at a formal hearing conducted by the Coast Guard in conjunction with the NTSB, Republic of the Marshall Islands maritime administrator and the Korean Maritime Safety Tribunal in September 2020, the NTSB said.

The Golden Ray’s ballast level figured prominently in that two-week hearing.

“If the vessel had kept the additional ballast on board that was discharged during the Freeport-to-Jacksonville voyage, this would have resulted in full compliance with the 2008 Intact Stability Code and likely would have prevented the capsize,” Lt. Ian Oviatt, a naval architect with the U.S. Coast Guard Marine Safety Center in Washington, testified.

Pilot Jonathan Tennant was guiding the Golden Ray out of St. Simons Sound in the predawn hours of Sept. 8, 2019, and he recounted the capsizing during the hearing.

“Immediately after applying 20 degrees of rudder, she began to rotate to starboard at a concerning rate,” Tennant testified. “When I applied starboard 20, I felt her lean to starboard, not an alarming amount, a normal reaction. She remained upright. At this time I thought that I was just over-rotating to starboard for some unknown reason. She continued the over-rotation to starboard while flipping over on her portside in a violent, rapid descent.”

Ship and cargo loss $208.5 million, salvage costs over $250 million

Tennant and all 23 crew members on board were rescued, although four engineering crew were trapped in the Golden Ray for nearly 40 hours.

“After the vessel capsized, open watertight doors allowed flooding into the vessel, which blocked the primary egress from the engine room, where four crew members were trapped,” the NTSB said. “Two watertight doors had been left open for almost two hours before the accident. No one on the bridge ensured that the doors were closed before departing the port.”

The loss of cargo, which included 4,161 vehicles, was pegged at $142 million. The value of the 656-foot-long Golden Ray was estimated at $62.5 million. The NTSB said salvage costs would total more than $250 million.

The NTSB said its investigation ruled out such possible capsizing causes as weather, a transfer of ballast or fuel, the propulsion and steering systems, the shifting of cargo within the vessel, and obstructions in St. Simons Sound.

The Golden Ray underwent 10 examinations between 2017 and 2019 to ensure it complied with International Maritime Organization requirements, the NTSB said. Two of those inspections were conducted by the U.S. Coast Guard while the vessel was berthed at a U.S. port. “No significant deficiencies were documented during the port state control examinations,” the report said.

Golden Ray wreckage remains in St. Simons Sound

Cutting operations concluded earlier this month and only two separated hunks of the wreckage remain in St. Simons Sound.

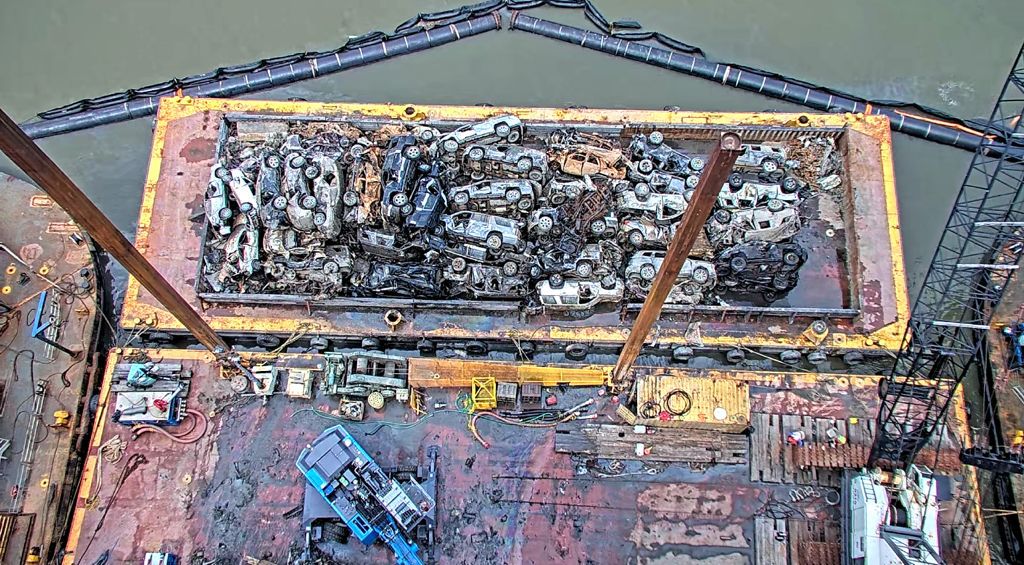

St. Simons Sound Incident Response said 266 vehicles were removed from one of the remaining sections last week.

“In addition to ensuring a safe lift of the section, weight shedding also increases the safety of dismantling operations,” it said. “Any sunken debris that remains inside the environmental protection barrier will be removed after the wreck sections are removed.”

All eight sections are being transported individually by barge to a recycling facility in Louisiana.

The dismantling operations have been hampered several times. Those work stoppages have been caused by such events as a May fire inside the wreck; a chain break in November 2020; “engineering challenges” in October 2020; a COVID-19 breakout in July 2020; and hurricane season precautions.

Investigator testifies Golden Ray violated stability regulations

Pilot radioed ‘I’m losing her’ as Golden Ray capsized

Alarm blared during Golden Ray capsizing

Click here for more American Shipper/FreightWaves stories by Senior Editor Kim Link-Wills.