If you are looking for a product that illuminates the shift in manufacturing taking place in Asia as a result of the U.S.-China tariff war, Peter Sand, the chief shipping analyst for BIMCO, suggests looking at U.S. imports of Christmas tree lights.

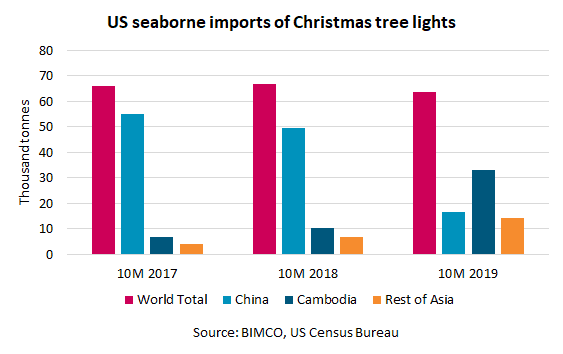

“Cambodia is basically taking over in supplying the U.S. with Christmas tree lights,” he said. In the first 10 months of 2019, China shipped 113 million fewer sets of Christmas tree lights to the U.S. than it did the prior year — a 66.1% drop from the same 2018 period.

In the first 10 months of 2019, when compared to the same 2018 period, U.S. imports of Christmas lights from all countries were down only 4.3%, but imports from Cambodia have increased 223% and Asian countries other than China and Cambodia are up 100.7%.

“These are mind-boggling numbers,” said Sand.

The changes illustrated by Christmas lights are taking place on a much larger scale, he said in a recent article posted on the BIMCO website and during a webcasts sponsored by both BIMCO and the Journal of Commerce.

During the first nine months of 2019, while seaborne containerized imports from Asia to the U.S. were up 1%, they were down 7.3% from China but up 31.6% from Vietnam and up 32.8% from Cambodia.

“The continued, albeit modest, growth in U.S. imports from the whole of Asia reflects a reshuffling of exporting nations that has occurred in the Far East. This has manifested itself in two ways,” Sand said.

“First, the trade war and added tariffs on goods from China has speeded up the process — which had already begun — of some manufacturing moving away from China in favor of its neighbors with lower labor costs.

“Second, the trade war has led to products, still being produced in China, being transshipped through neighboring countries to change their country of origin and thereby avoid additional tariffs when they arrive in the U.S.,” Sand said.

However, the shift in manufacturing has not been a boon to the intra-Asia container trade, he said, pointing out that in the first three quarters of 2019, volumes were flat when compared to the same period in 2018. Neither have freight rates — both spot rates, as measured by the Shanghai Containerized Freight Index (CCFI), or contract rates, as measured by the China Containerized Freight Index (CCFI) — to the U.S. West or East coasts seen a positive effect.

“The boost that could have been expected from shifting manufacturing and transshipment has not come to the shipping industry, which instead is feeling the pressure from slowing overall exports from the region. This may be because transshipped volumes are primarily being transported by land from China into neighboring countries before being put on a ship,” he said.

Sand said there has not been the front-loading of shipments this year into the U.S. as there was in late 2018, which he noted led to higher freight volumes and higher freight rates.

He does not expect IMO 2020 — the agreement reached at the International Maritime Organization to require ships to use more expensive low-sulfur fuel or equip their vessels with scrubbers to remove sulfur oxides from engine exhaust — to drive changes in the container ship industry such as increased slow steaming or an increase in ship sizes.

Sand said the higher cost of cleaner fuels or scrubbers needs to be passed on by ocean carriers, but he also said their ability to do so will depend on the market conditions.

“Only in the cases of that being absolutely impossible, more slow steaming may come around,” he said.

While increasing the size of ships can lead to economies of scale by reducing the cost of moving each container, Sand noted that process has been going on more or less continuously on almost every trade around the world since 2012, when demand started to stagnate and ultra large container ships (ULCS) started to get delivered at a high pace into the Asia-Europe trade.

As ULCS got put into the Asia trade, the existing ships on that round “cascaded” onto other routes, for example from Asia to North America. In turn, ships in the Asia-U.S. trade cascaded into other routes.

Sand believes “it will be difficult to single out any effect from IMO 2020 on upscaling on various trades from what is constantly going on with the whole cascading thing.”

The problem for the container shipping industry, he noted, is that while larger ships can reduce the cost of carrying containers if a ship is full, carriers have struggled to fill up the very large ships and raise freight rates.

“I think the trend is to continue that we’re going to see bigger ships being fed into every trade, but I’m not seeing IMO 2020 pushing this further, unless we see absolutely no effect from the efforts of carriers to pass on the extra costs” related to IMO 2020.

Sand said 2020 “will bring not only the sulfur cap but also skewed exports caused by the Chinese New Year. Pushing out goods ahead of widespread factory closures may bring a boost in January before a slow, and possibly painful, February awaits carriers.”