Many truckload carriers will be happy to shut the door on a tumultuous 2019. Following a 2018 that many consider to be the best year for trucking profitability in decades, 2019 was almost the exact opposite. 2019’s yin to 2018’s yang illustrates how sensitive trucking is to the supply-and-demand factors that exist, due to its almost pure free-market structure. If Adam Smith wrote “The Wealth of Nations” in 2019, he surely would have used trucking to illustrate the “Invisible Hand of Supply and Demand.”

For most carriers, the biggest competitive advantage this year was having a banker (or bankers) who understands the historical market cycles in trucking, combined with an extremely soft used truck market in the second half of the year. It could be argued that trucking failures could have been two to three times worse had it not been for depressed used equipment values. Trucking companies got hit with multiple gut punches this year – low spot rates that have translated into lower contract rates, rising insurance premiums and a flood of capacity that didn’t seem to recede until early fall.

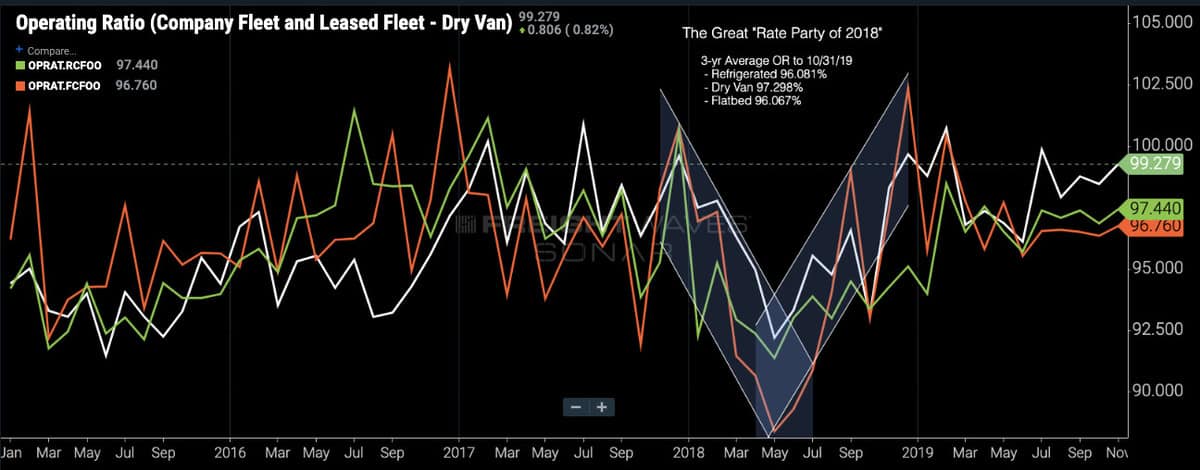

Despite the best efforts of millions of smart and hardworking people, it would appear (unfortunately) that trucking has a terminal velocity on profit. Last March, as rates were starting to drop, I spoke to an industry veteran who declared stoically, “I’ve been in the business for over three decades, and I can state with certainty that over any three-year period it is almost impossible for any refrigerated carrier to drop below a 97% operating ratio.” At first, especially with 2018 then in the recent rearview mirror, I thought he was being a bit pessimistic, but as the year unfolded and I looked at the data (see below), that one statement got me thinking more and more about risk versus return, barriers to entry and structural industry changes.

SONAR Ticker Symbols: OPRAT.RCFOO, OPRAT.VCFOO,OPRAT.FCFOO

- Refrigerated: 96.081% (average 3-year operating ratio for 98 carriers)

- Dry van: 97.29% (average 3-year operating ratio for 103 carriers)

- Flatbed: 96.067% (average 3-year operating ratio for 31 carriers)

We are at a critical intersection for trucking and transportation globally. It is my opinion that within the next 12-15 years, shippers (the ones that produce or control the distribution of goods) will be removing many carriers (and brokers) from their transportation equation. This will be done via the combination of semi-autonomous (maybe autonomous) trucking and complex software applications. This is vertical integration, and it’s happening in all industries. What this translates to is an increasingly smaller window for trucking companies to remain sustainable and profitable. In light of this prediction, it is time for carriers to take control of the supply chains and get paid a return relative to the growing risks they face. (Hint: It’s much more than 3.5%.)

The list below is an attempt by someone who owns no trucks to suggest a path toward higher profit margins and more (not fewer) barriers to entry. Those who know me realize I am not afraid of a healthy debate, and I hope this article provides discussion fodder and suggestions to increase carriers’ margins.

Trucking needs more barriers to entry

Based on experience, stating this in a room full of truckers can turn sideways very quickly. However, when you put the statement in context, the outrage diffuses very rapidly. Trucking company owners did not buy mansions in 2018, they bought more trucks. It’s human nature – do more of what you’re good at. What happens when you increase the supply of a good? The price of that good drops, along with the marginal profits of the producer. Trucking needs more barriers to entry and barriers to self-harm. Hardening insurance markets are a free-market example of a growing barrier for those new entrants to the trucking game, and those that did not (and will not) put safety first.

On the regulatory side, the Drug and Alcohol Clearinghouse will undoubtedly limit market capacity. Carriers also should embrace mandatory hair-follicle testing. If anecdotal evidence from a group of enterprise carriers is true, there are a significant number of drivers in seats who never should have been given the keys to a truck. The above barriers will make trucking safer and reduce the effects of human nature and the resulting lower margins.

(Photo credit: Jim Allen/FreightWaves)

These barriers should be embraced by all trucking industry participants, from members of Owner-Operators Independent Drivers Association all the way up to enterprise carriers.

Copy the airline industry playbook on ancillary revenue

Currently, the top quartile performers in the TCA Profitability Program (based on gross margin) also have the highest percentage of accessorial revenue relative to total revenue (2.96% versus 0.71% for bottom quartile performers). Accessorial revenue in trucking includes fees for services above and beyond linehaul and fuel surcharge revenue. The most common accessorials are detention, stop charges, load/unload and lumper fees.

I recently read an article in Forbes titled “Here’s What the Trucking Industry Could Learn From Airlines” by Frank Holmes. Although the author was a bit uninformed on the operating realities of today’s trucking industry, he did highlight the growth of ancillary revenue and its importance to the bottom lines of all airlines. The article stated that the global airline industry generated $109.5 billion in ancillary revenue this year. More staggering is that the fees generated covered more than half of the entire industry’s fuel bill (the largest variable operating cost for airlines).

If a carrier’s pricing department can get scientific about the unique needs of its shipper customers and offer a menu of unique value-added services, it can accomplish two things. First, it will allow the carrier to come in at the target rate established by the 23-year-old logistics manager who has been on the job for three months. Second, it can provide the motivation (and financial incentive) to differentiate the product offering of the carrier.

Replace odometers with ELDs for truckload pricing

This is perhaps the most important change in this list. The largest impediment to suitable margins (15%+ net margins) in trucking is the mismatch of work performed versus the actual time required to perform that work. Inefficient distribution centers and infrastructure built in the 1950s that can’t handle 2019 volumes are the primary reasons why rate per mile is the most outdated pricing mechanism in any industry. In order for the default pricing mechanism in trucking to change, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) will need to establish a third-party certification process or agency for electronic logging device (ELD) providers. Grading your own test works for the honest few and is (and will continue to be) abused by many. Having access to audited/verifiable data is the missing link for both parties to the truckload transaction. Carriers need to understand effective transit times, along with the actual behavior of their shipper clients or prospects in order to be able to quote a rate per hour.

Getting strategic with brokerage

Instead of brokerage being the ugly stepbrother of the carrier, today’s trucking companies need to invest and develop the talent to put brokerage at the top of the organizational structure. During 2018’s rate party, one carrier relayed to me that his company rejected almost 600 loads from one customer over a five-month period. It wasn’t giving its brokerage operation any chance at these loads. The asset side was doing its thing and the brokerage was eating what it killed – the way it’s always been done.

The majority of the top-performing members of the TCA Profitability Program have brokerage operations that can not only handle overflow freight but also sell like nobody’s business. A new trend has emerged in the last couple of years in which the logistics team is placed in front of the asset and carrier procurement teams on the brokerage side. That logistics team thoroughly understands the capacity constraints and highest margin lanes for the asset side, along with market realities of the brokerage side. The result is a decision tree guided by software, which equates to more dollars being retained by the collective business than it would have using a different structure. It makes me sick to my stomach when you hear that someone wants to pay you money (market rate) and you can’t give him the product or service.

Profits before truck count

Heartland Express does not care about truck counts. It is one of a very limited group of carriers that publicly states this. Truck count has always been the yardstick by which success has been measured in trucking. In fact, almost 100% of the time when I am talking to an executive with over 500 tractors about benchmarking, he/she states, “I only want to compare or be in a group with carriers of similar size (large).” I can state definitively, especially based on the data that has been reported this year, that size does not equal higher margins.

Twelve of the top 20 performers in the entire TPP program are under 165 tractors. How do we reinforce margin before truck count? One way is to use all trucks in your KPIs (seated and unseated). If you have unseated or underutilized tractors, it will become very apparent when you divide revenue and margin by total truck counts. Likewise, one of the newest KPIs we introduced has been revenue per on-duty plus driving hours. The disparity between the top and bottom performers would make your banker’s head spin. In short, we need to replace the term truck count with margin per truck as the de facto yardstick of trucking success.

What’s 2020 got in store for truckload carriers?

If you’re a carrier, and this article does not provide you with a sense of urgency, it’s either time to sell or to pat yourself on the back. I’ve spoken to multiple companies that are attempting to do some or all of the items above. The key concept for everyone to understand is that trucking companies are not selling trucking, they are selling time. You need to price with time in mind and operate to optimize effective transit and delivery times – not just rate per mile.

Based on anecdotal and empirical evidence, it would appear that 2020 will see a general upswing in rates and corresponding margins. In the past month, I’ve had numerous discussions with brokers who have relayed the impression that capacity has tightened year-over-year. Likewise, TPP members have responded (via ad hoc surveys) flat or very little growth forecast for 2020, unlike this time last year, when TPP members forecast an average truck count growth rate of 6.5%. Let’s hope the invisible hand gives trucking a nudge toward profitability for all of 2020. I leave you with one mantra to repeat for all of 2020 – margin before truck count.

Art

with the advent of onkine digitial brokerages how can one justify an investment into a practice that is being outdated by those practicing it. being a bottom of the barrel brokerage that inspires boiler-room type of sales isnt something thzt we should be supporting. There are already many regulations for the trucking industry, adding more barriers to entry seems to be overkill, and can be construded as a pay-wall. what we should do is provide barriers to entry for brokers, make em take a standardized test. How can a 18 year old TQL broker that doesnt know west from east tell me what my time is worth? How can they tell me that the market is tough and that 500 miles for 400 USD should be taken with a smile, when all he did was underbid all the other brokers. The problem with critically commentating on state of a market such as for example NE seaboard dry van, requires you to be in the industry. Saying that we should broker more only puts more people into the supply chain lowering the share of food on the plate. Simplicity is key, and with the burgenoning eave of technology i await the time when there will no ” for profit brokerages”.