The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of FreightWaves or its affiliates.

Since the beginnings of COVID-19, the political rhetoric masking the severity and economic impact of the virus has piled up to levels we have not seen since the U.S.-China trade war. Just as the flow of trade refuted the trade war promises and winning declarations, the same can be applied to the impact and ruthlessness of C-19.

(Photo: PortMiami)

I have said since the beginning of the U.S.-China trade war that “containers don’t lie.” This is more than a catch phrase. It is the physical truth about a country’s economic health and its trade relationships. Globalization has connected the world. Trade has supported this relationship. It has also shown the crippling impact it can have when a country shuts its borders.

Millions of jobs are connected to this globalization. These occupations expand beyond maritime and logistics into retail, medicine, the local sandwich shop and more. The list is nearly endless. The blue economy is the heartbeat of the world. The production and movement of trade is the oxygenated blood carried through every country’s economic veins.

This fiscal vitality can be measured by the productivity at the individual port systems. Every port is a microcosm of its society. Every port has its specialty and different trading partners. The Port of Miami (POM), known as the “Cruise Capital of the World,” transformed almost overnight into a rotating parking lot for ships with no places to go while servicing its trading partners.

(Photo: PortMiami)

With the cruise industry landlocked, COVID-19’s impact on this segment goes beyond the travel industry. According to a 2019 POM impact study conducted by Martin Associates, the cruise industry consumed $336.1 million of food, liquor, flowers, logo items and bon voyage gifts. Most of the food and liquor being loaded onto these cruise ships is domestic, not imported.

“Approximately 4,000 containers of products are consumed by the cruise industry,” explained Juan M. Kuryla, Port Director and CEO of PortMiami. “About 60,000 to 70,000 people have a job directly or indirectly at the Port of Miami alone. In the state of Florida, 150,000 people are affected. Our container trade is paying the bills right now.”

(Photo: PortMiami)

For the fiscal year October 1st to March 15th, POM was up 7% compared to fiscal 2019. “That was before COVID-19 hit,” explained Kuryla. “Then we began to see the descent.”

The undulating wave of trade destruction caused by COVID-19 can be tracked through the timeline of the three trade routes POM serves – Asia, Europe and Caribbean/Latin America.

In March, the port saw a 52.2% drop in container volumes in and out of Asia. That region represents 36% of the POM annual trade. The pickup in volumes in April and May was the long-awaited backlog of containers accumulated between the Chinese New Year and the extension of manufacturing closures because of the coronavirus. This was not a reflection of consumer demand. The “surge” was the movement of trade playing “catch up.”

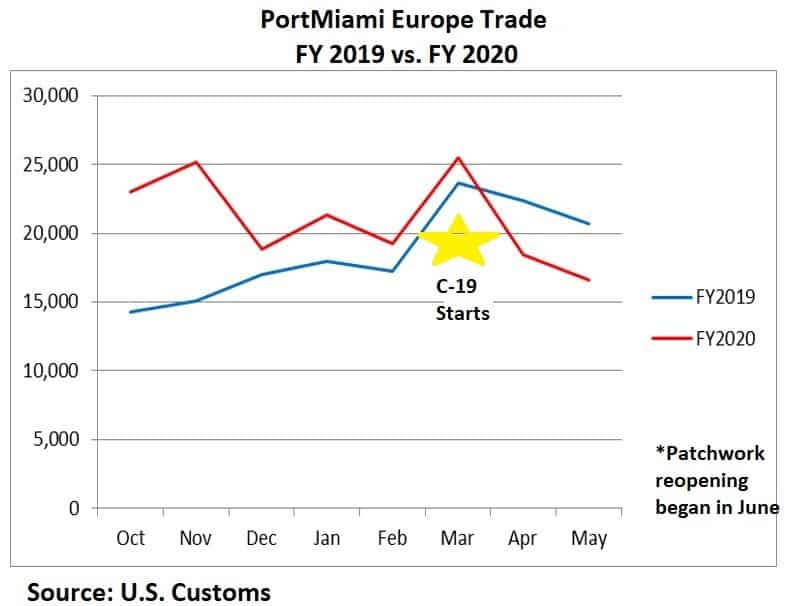

The upswing in trade falls in line with the decline in trade out of Europe. The trade timeline falls in lockstep with the pandemic spreading throughout the world and countries having to shut down to combat the spread.

Europe makes up 13% of POM annual trade. Volumes were up by 7.8% in March, and then dropped by 18% in April and 20% in May.

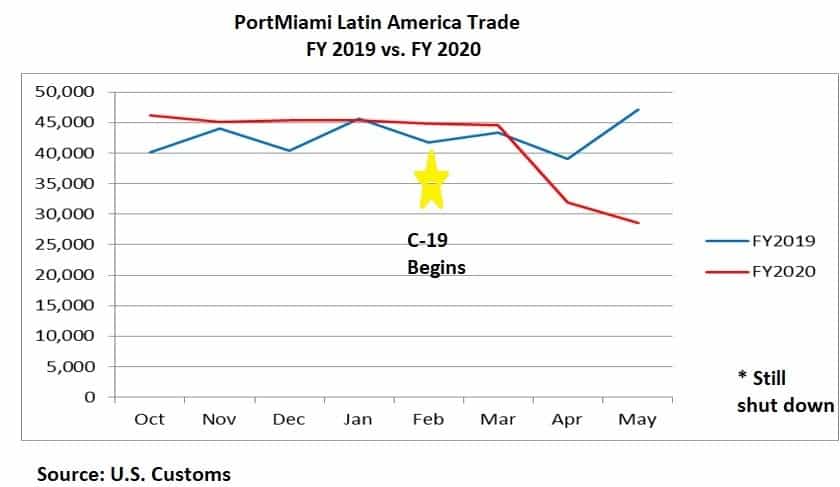

The most valuable trade lane for PortMiami is Latin American and Caribbean. This route generates 45% of the port’s total volume. The precipitous drop began in April – a fall of 18.2%, and a plunge of almost 40% in May. The trend continues. “Latin America is closed,” said Kuryla. “The quarantine orders in these countries were very stern. People couldn’t go out and go to restaurants, so consumption dropped, thus no export to these countries.”

“Until Latin America opens up, this loss in trade will continue,” said Kuryla. “We are down 150,000 containers. That’s an overall loss of $9 to $10 million in revenue directly to the port. It does not include the loss of revenue generated for the entire supply chain – trucking, banks and the post-financing letter of credit of warehouses and manufacturing. That’s a loss of $20 million in trade.”

Kuryla says the June volumes are estimated to be down by 15%. He expects the peak season to be down as well.

(Photo: PortMiami)

“Thankfully the container volumes were stronger earlier in the fiscal year to help offset these losses,” said Kuryla. “But for 2020, we’ll end up being down about 10 to 12%. It’s not terrible, but clearly not good.”

The heartbeat of trade is still beating. But the strength of that rhythm is dependent on the actions of global leaders trying to strike a balance between health, safety and reopening. We are seeing the stumbles. Hopefully lessons from those missteps will be learned.