Experiencing the red dragon first-hand

Ten years ago, I would likely have been studying and writing Chinese characters in my one-room apartment in Beijing, wondering how the students of China were able to do this much studying every night. After graduating from college in the spring of 2009, I chose to study abroad in China for the summer at Beijing (Peking) University. Since this was a post-graduation experience, I was hoping to learn Mandarin while enjoying some time traveling and visiting sites in China, but instead I was introduced the hard way to modern Chinese academia and the intense work ethic of its students and teachers.

Rather than taking weekend trips or going out with friends, I was busy writing Chinese characters and making sure I memorized the proper order for each and every stroke to ensure I was able to accurately write these characters in front of the class on the whiteboard every morning. We were not allowed to use English at any point while at school to ensure we were always practicing and reinforcing our lessons. It was arguably one of the most challenging and rewarding academic experiences of my life, and it introduced a side of China that will be forever etched in my memory.

When I arrived in Beijing, China was coming off of hosting the 2008 Olympic Games. If you watched the Opening Ceremony of these Olympic Games, you likely remember the stunning production that was on display. It was as if they meant to say, “China has arrived and is here to stay.”

The importance of this moment for the Chinese cannot be downplayed, and the success of those Games provided its citizens with an enduring sense of pride that was easily felt. The entire country was extremely proud of what they had accomplished, especially after having persevered and endured through many years of war and hardship during much of the 20th century. From civil war and fighting the Japanese during World War II, to Mao Tse Dong’s many failed campaigns that resulted in an estimated 20-30 million deaths, this modern China was determined to show why this time was different. It was eager to prove that it now belonged among the world’s great powers.

This was a side of China that was not often read about in the news or heard about on television. It was a China that was operating at a pace that was difficult to comprehend, unless experienced first-hand. It was clear to me then, just as it is now, that China was/is on a path to become the next major challenger of American hegemony on the global stage; and thinking back 10 years ago to my days in Beijing, it is now apparent that their moment has finally arrived.

How China became the largest economy in the world

China’s unprecedented rise to economic power was made possible through a unique combination of a communist government that had the ability to allocate resources and labor with incredible efficiency, and a “dual-economy” allowing for privatization within “special economic zones.” This distinctive combination of communism and capitalism is largely believed to be made possible by China’s enduring top-down culture based on collectivism with a “country and family before self” mentality, which many attribute to the teachings of Confucius (Confucianism). Together, these factors have created a set of powerful market dynamics that have made it possible for China to scale its economy at an unprecedented rate.

In 1985, Deng Xiaoping began changing the country’s direction with key economic reforms that would quickly pave the way for the road to privatization within China. By the 1990s, the country had finally opened up its doors to direct foreign investment, and from that point forward, China built its economic growth primarily on low-cost exports of machinery and equipment, while the government spent massive amounts of resources on state-owned companies to fuel those exports.

American companies were quick to realize opportunities to invest in China and were attracted by its massive low-cost labor force. Many companies chose to outsource production from the U.S. to China, where they could realize significant savings on labor. By the early 2000s, much of what the U.S. consumed was being produced in China. This led to even greater economic reform under Hu Jintao, and between 2001 and 2004, state-owned-enterprises decreased by 48 percent, and by 2005, the domestic private sector had reached 50 percent of China’s overall GDP. In 2018, China was officially recognized as the world’s second-largest economy by GDP, number one in Asia by GDP (overtaking Japan), and the number one economy in terms of purchasing power parity.

During this period of rapid economic growth, China began to invest in the dollar through U.S. Treasury Securities as a way to peg its own currency, the Yuan. China now holds the largest amount of U.S. Treasury securities in the world; it owns $1.12 trillion of U.S. debt.

For many years, China has valued its investments in the U.S. dollar as a means to stabilize or manipulate its own currency by devaluing it whenever it feels the need to boost its exports. This is problematic for the U.S. because the Chinese investments in U.S. debt means that it holds leverage against the dollar – it threatens to sell its investments whenever the U.S. pressures China to increase the value of the Yuan. This tension has increased in recent years with the value of the dollar increasing 25 percent between 2014 and 2016. This forced the Chinese to further devalue the Yuan, which in turn has created what the U.S. Government would recognize as unfair trade practices.

Donald Trump won the presidency in 2016, in part by running on a platform accusing China of “ripping off” the U.S. Since then, tensions between the two countries have reached a “tipping point” with neither side wanting to “give in” to the other.

The U.S.-China Trade War is reshaping the global economy

The U.S. is now going head-to-head with China on the global stage, and the resulting trade war has had a dramatic impact on the global economy. Since the U.S. has a major trade deficit with China ($419 billion in 2018), U.S. importers have been greatly affected by the increase in tariffs on Chinese-made goods. Due to the tariff threats in 2018, there was a major rush to get as many shipments to the U.S. as possible before the tariff deadline. This resulted in increased costs in the form of stored inventory in warehouses across the country, which will likely be passed on as increased costs to consumers. With additional tariff increases being announced and another round of $300+ billion on the table, U.S. importers are struggling to decide whether to bring more products in early, or wait it out to see if China and the U.S. can reach an agreement.

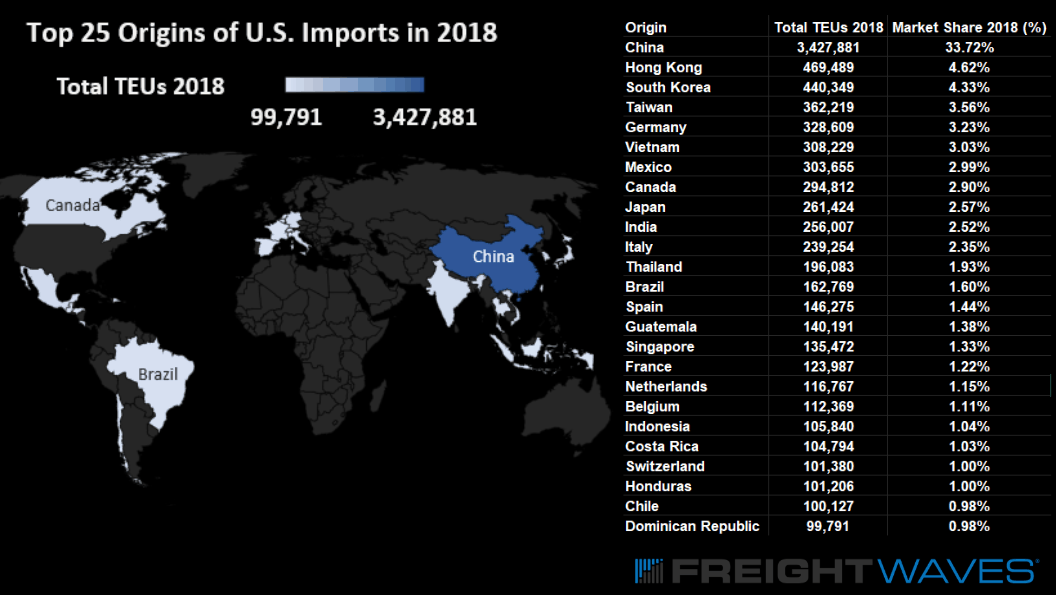

China had a market share of 33.72 percent of total U.S. imports

This trade war has escalated further with the Chinese raising additional tariffs on U.S. exports to China. It would appear that these tariff increases between both parties are likely to have the heaviest impact on Chinese producers and American farmers when looking at both countries exports, but U.S. importers and American consumers are also hanging in the balance.

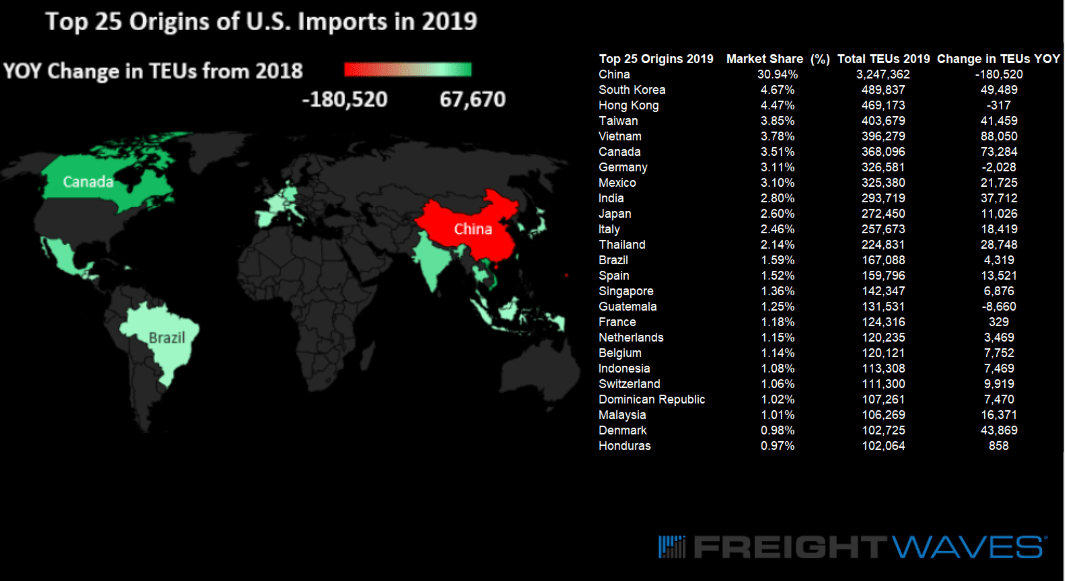

Due to continued escalation in the U.S. and China trade war, those managing supply chains in the U.S. have started to look at the best ways to mitigate the potential risk of tariff-related disruptions, and that has included moving production and/or sourcing outside of China to neighboring countries in Southeast Asia and the Indian subcontinent. When looking at the U.S. import data year-over-year between January 1st and May 20th (2018 to 2019), it is striking how quickly some U.S. importers have relocated their production and/or sourcing to countries outside of China. During this period, imports from China to the U.S. have decreased by 180,520 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs), while many countries outside of China have increased by tens of thousands of TEUs.

Source: FreightWaves – Represents the total market share, total TEUs year-to-date for 2019, and the change year-over-year in total TEU volumes from January 1st through May 20th (2018 & 2019)

This has led to a major decline in TEU volumes for the country that has held the largest market share of total U.S. imports for many years. It is easy to see that the trade war is undoubtedly affecting Chinese exports. However, we know that there was a good portion of freight that moved last year that would have likely moved this year because U.S. importers tried to beat the proposed tariffs that were to go into effect January 1, 2019. So, it is not yet known exactly how much of this is related to reduced overall production within China, but due to the recent tariff announcements there have been many reports of U.S. importers being frustrated by the deteriorating U.S.-Chinese trade relations, and they are likely to mitigate any additional risks these relations pose by moving their production and sourcing operations to countries with friendlier ties to the U.S.

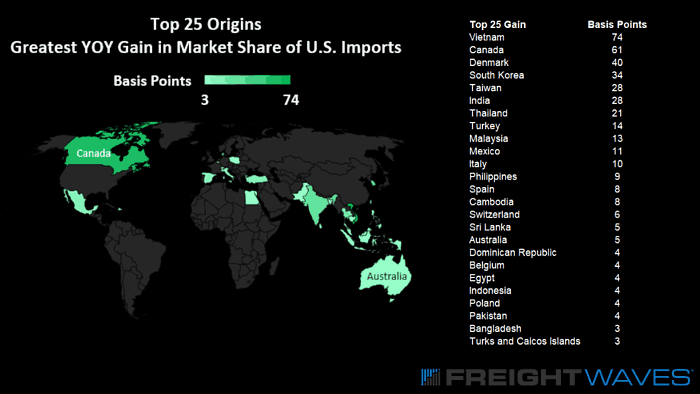

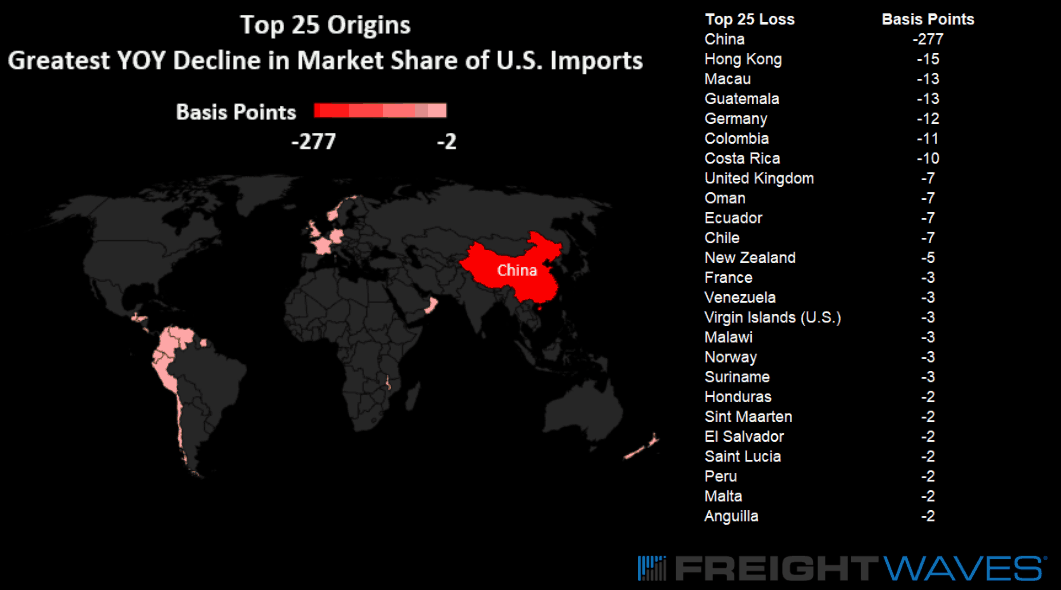

In looking at the top 25 countries of origin for U.S. imports, and measuring their total market share and how it has changed year-over-year, the winners and losers become much more apparent. Even small trends in ocean freight can have incredibly large impacts on global freight flows. Using this assumption, upon closer examination of the year-over-year changes in overall market share of U.S. imports among all countries of origin, one can clearly see the trends of how U.S. importers seem to be adjusting to deteriorating U.S.-Chinese relations. Below are two heat maps representing the countries that have gained and lost the greatest amount of overall market share year-over-year. If trade relations continue on their current path, one could only expect these trends to continue. The overall effects of these trends are yet to be fully understood as they relate to the Chinese and U.S. economies.

Source: FreightWaves

Represents the 25 countries of origin that have gained the largest amount of market share in U.S. imports

– Dates examined are from January 1st through May 20th (2018 & 2019)

Source: FreightWaves—Represents the 25 countries of origin that have lost the largest amount of market share in U.S. imports—Dates examined are from January 1st through May 20th (2018 & 2019)

Jon

Errrrr….China is NOT the world’s largest economy! The USA is – by a whopping 50% (approx $21T v $13T). How could you get this fact so wrong – especially in the headline?

Sloop John B

I think he is referring to the rankings where gross domestic product is based on purchasing-power-parity. According to the IMF in 2018, China’s GDP (PPP) is larger than the US.

I enjoyed the article. Interesting read.