FreightWaves features commentary from Market Voices – contributors with unique knowledge of numerous transportation/logistics/supply chain sectors, as well as other critical expertise.

The transportation of grains is a large volume and profitable business sector for railroads in the U.S. and Canadian markets.

Grains are harvested seed of the grass family. Also called cereals, the basic grains include wheat, oats, rice and corn. Grains are considered a staple food because they are routinely eaten by mankind and in many areas of the world provide nearly half of consumed carbohydrates.

Grains are also used to feed livestock and to manufacture products like cooking oils, cosmetics and alcohols. In addition, corn is also an ethanol fuel source.

In the United States, corn and wheat are the two largest farmed grain crops. There is also a large soybean crop – although technically soybean is an oilseed.

After harvesting, grains typically move from the farm to local storage silos. Some silos are operated by farmer cooperatives – others are independent logistics facilities. Movement of grains can occur throughout the year provided that the grains are stored to protect them from moisture.

Each grain is grown in different clusters of states. Corn is grown in many states, but just five states – Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska – account for nearly two-thirds of U.S. corn production. The top five U.S. wheat producing states are Kansas, North Dakota, Washington, Montana and Oklahoma. Soybean production is centered in Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota.

Which transport mode?

Trucks have cost advantages for shorter distances (less than 250 to 500 miles) and function primarily as the short-haul mode between farm and local silos.

A typical truck has the capacity to move 20 to 30 tons of grain. Some super-trucks in Canada can move up to 45 tons of grains on designated local roads – which is the equivalent of about 57 acres of farm production.

Overall, trucks might have nearly a 70 percent share when moving domestic corn.

However, when examining export movements of all U.S. grains, the railroad share jumps to between 33 percent and 40 percent. Trucking’s share of exports is often less than 20 percent. Barges move about 50 percent of exported grains. These modal shares vary significantly depending upon where in the country the shipments are moving and whether for the domestic or export markets.

Rail’s economic advantage comes in large part from each railroad car’s capacity of up to 100 tons. That’s the equivalent of three to four truckloads. The newer 5,400-cubic foot covered hopper railroad grain cars can hold and then move the equivalent of about 115 or more acres of harvested grains per car.

Linked together, a 100-railcar length train can move between 9,000 to 10,000 tons of grain. That’s the equivalent of more than 11,000 harvested acres.

Where navigable waterways exist, barges have a lower transportation cost. A barge can hold the equivalent of roughly 15 rail cars and then moves along the water at a very low energy cost – often less than half of rail’s per ton-mile cost.

The economics of unit rail trains

There have been three technical advances in the past half century that have helped U.S. railroads retain market share in the grain business.

One engineering advance was the development of heavier axle loads – each freight car increases its net cargo load. Total gross carloads increased from 263,000 pounds per railcar to 286,000 pounds – and on some rail routes to 315,000 pounds. Spread out along four axle sets per railcar, this increased the vertical loading from 30 metric tons to as much as 35 metric tons per axle on some strategic grain routes.

The cost for this operational change was about an 18 percent increase in annual track and bridge maintenance costs. The net savings (cost advantage) came from higher net loads per railcar and per train movements.

Secondly, the railroads also experimented with running longer trains. Trains that once averaged 50 to 70 railcars were expanded to 90 and 100 railcars.

As a third initiative, the railroads set up unit grain trains. The Illinois Central Gulf Railroad (the ICG) was among the first to experiment with this idea. ICG worked with Cargill in 1966 to see if the premise of unit coal trains would work for grains.

Instead of renting individual railcars for grain transport, ICG negotiated with Cargill in 1966 to rent an entire train. The potential was nearly a 50 percent reduction in the rail rate Cargill would pay.

The challenge was that Cargill had to re-engineer its silo tracks to load an entire train at one time.

Cargill accepted the unit car challenge. It even introduced dryer technology to better store grain and keep it in prime condition well beyond harvest until the unit trains were assembled.

Cargill invested capital in an expanded 3.6 million bushel export grain complex near Gibson City, Illinois. During the winter of 1967, the first Cargill/ICG 115-railcar unit train moved from the silos at Gibson City with approximately 400,000 bushels that were delivered to Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Once emptied, the entire train set returned to Gibson City in just five days.

The result was that Cargill committed to a minimum of 56 round trips the following year, and the ICG delivered more than 22 million bushels of corn to Baton Rouge. Soon after, Cargill opened similar unit train loading terminals in Tuscola, Illinois and at Linden, Indiana. Other railroads began to adopt the unit train/larger silo terminal business model.

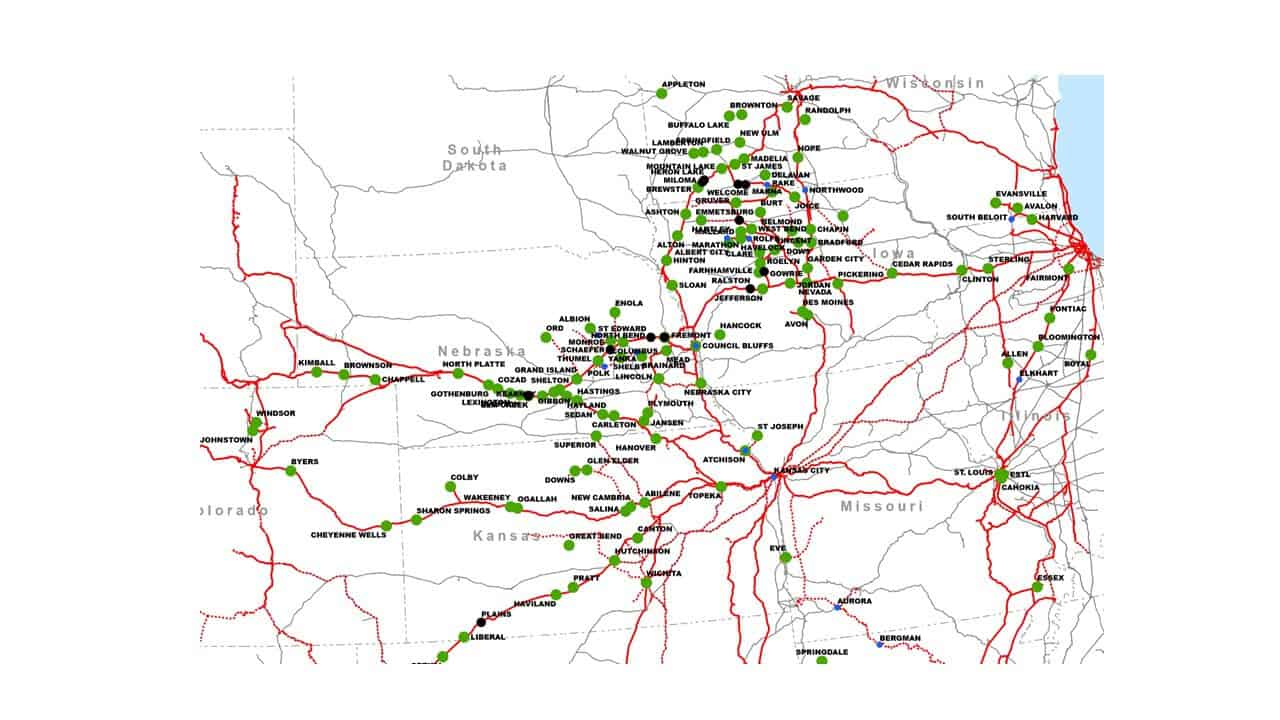

The image below is a partial map view of approved terminals in Union Pacific’s Grain Shuttle Program. Union Pacific offers a shuttle grain train service with a dedicated set of 75 or 110 covered hopper railcars for loading of whole grains that move as a unit (train) from one origin to one destination.

The rail grain market in 2019

During an average week, U.S. railroads will move between 18,000 and 26,000 carloads of grain. When rail is used to move grains, about 70 percent is by unit trains.

Single railcar to five-railcar movement of grains is a very small percentage of the rail grain business today. Less than 10 percent of rail-moved grains use a single car to a five railcar movement.

Overview of the 2017 volume and tonnage grain market for the U.S.

In 2017, 144 million tons of all grains were moved by rail. Of that total, there were just over 70 million tons of corn, 30+ million tons of wheat and close to 28 million tons of soybeans moved. The 10-year rail volume pattern has varied from a low of just over 120 million tons to a high in three years of close to 150 million tons. For 2017, grains amounted to 8.9 percent of total U.S. railroad tonnage.

In 2017, railroad gross revenue earned from the movement of these grains was approximately $5.5 billion. That was about 8.5 percent of all U.S. rail freight revenues.

By type of grain, $2.5 billion in revenue came from moving corn, $1.6 billion came from transporting wheat and $1 billion was from soybeans.

There are a few specialized rail grain movements to note

The railroads transport ethanol as a manufactured corn-based fuel. During 2017, approximately 50 million bushels of corn were used to manufacture ethanol. The rail tonnage and rail revenue from ethanol transport was not included in the information above. From a railroad marketing perspective, ethanol is primarily a tank car business.

The railroads also move some international maritime containers with specialty grains. From a base of almost zero container grain in 2006, recent research identifies as much as 3 percent of rail-moved containers are hauling “farm products” classified as STCC code group 01. Otherwise empty containers in 40-foot/20-foot sizes are returning to countries like China. Instead of being empty, they are loaded with grains. Rail intermodal terminals at Chicago and Minneapolis-Saint Paul are two grain container loading centers. How much this sector will grow is uncertain.

Acknowledgement:

- Association of American Railroads (AAR) 2017 statistical data

- USDA Agricultural Marketing Service

- Kimberly Vachai, PhD., Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute

- Gord Leathers, Country-Guide

- US Grains Council