The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of FreightWaves or its affiliates.

About once a year, someone pens a North American rail merger column. Why not one from a rail economist? This is not a “will happen” projection. It’s a strategic scenario question.

If a merger proposal is announced, here is a quick checklist of what you will want to examine as to details.

Suggested railroad M&A process checklist

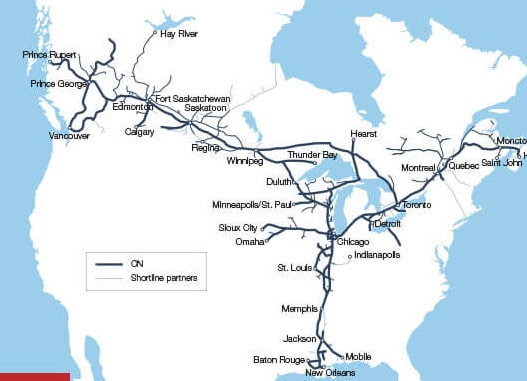

For many, the last serious merger was the Canadian National’s (CN) ICG and EJ&E integration. CN created a three ocean link-up from New Orleans via Chicago to both Halifax in the east and Vancouver and Prince Rupert in the west.

Ironically, transcontinental west to east and north to south rail service between the oceans is offered within the United States only by a Canadian company.

Two decades later, everyone in the United States seems comfortable with the rail status quo.

An exception was E. Hunter Harrison. He wanted to push the opportunity for a $30 billion merger between the Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) and Norfolk Southern (NS). Interesting how the Canadians were the aggressors.

That CP-NS merger would have been the first to test the year 2001 USA regulatory rules for railroad mergers. It would have had to prove it was pro-competition.

Norfolk Southern backers and rail customers seemed to prefer to go it alone. Canadian Pacific dropped the deal before the federal Surface Transportation Board (STB) could see how its pro-competition rules might be applied. I am not sure that the U.S. Department of Transportation ever voiced its opinion.

Since then, there has been a two-decade long merger hiatus. There has been no intellectual study of the issue, and no test of the STB rules that any proposed acquisition or merger demonstrates increased competition.

(Photo: Norfolk Southern)

Therefore, the industry has generally ignored the continually diminishing rail freight role as inconsequential public policy. Too harsh a critique? Maybe not. What is the role of the modern-era STB regulator?

A world without railroad mergers

Think of that possibility. What if there had been no mergers? An early 1960s report showed that according to some there were as many as 6,000 railroads in the United States at one point in time. They all started as small operations when the horse and buggy was the competition.

By the turn of the 20th century the number was down to about 1,200 railroads, and down to around 410 by 1955.

Then the number dropped to just 76 Class 1 large railroads. Today, there are just seven – with more than 500 short line companies.

(Photo: Library of Congress)

Some say that the seven Class 1 carriers are just too large to be effective and service-oriented. But that “too big” size assumption pales against the high efficiency of organizations like United Parcel Service and the U.S. military logistics command service. They are not too big.

But why merge?

There is no financial necessity caused by any of these seven Class 1 carriers being likely to fail in the near-term.

That failure risk argument drove the mega-merger of CONRAIL and then the later Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad/Southern Pacific Railroad merger. Later still, the Southern Pacific-Union Pacific merger had some elements of rescuing a struggling carrier. That is not the case in 2020.

What might be the central argument for a 2020 to 2023 merger period is the slowdown in rail freight. The volume gains year-over-year are falling behind the trucking gains. This was noted before the coronavirus pandemic hit.

The exception might be in Canada and possibly along some Mexican corridors.

Within the United States, there are signs that the Class 1 railroads are losing market share and market relevance.

They are not going out of business. They are just not growing as our economy diversifies away from industrial rail-moved goods. And so far they have developed no replacement for lost coal traffic.

One left-behind growth market to note is the Midwestern region, where the rail carrier ownership of eastern versus western distinction leaves a shallow region of states with a lower service role.

That shadow area covers the Mississippi River drainage area, where the cost of a two railroad interline movement makes rail freight a poorer choice against the often-available single company service crossing those states.

It’s a type of cargo desert. Some might compare it to the market shadow effect when a large airport hub like Chicago O’Hare competes with the nearby Milwaukee airport.

The simple translation is that cargo from Indianapolis bound for Des Moines or from Little Rock to Louisville suffers from a two-carrier required interline rail haul.

Those hauls are not as cost-competitive as a one carrier Pittsburgh to Des Moines rail movement. Why? Because that is a single carrier service.

Interline service, because of an ownership boundary along the Mississippi River region, adds both delay cost (time) and an added car switching expense. The added expense is to cover yarding costs plus two railroads seeking to add a charge that covers their respective general and administrative costs and profit margins.

After a transcontinental merger, the “market shadows” would disappear.

Success?

What were the key efficiency improvements over the past four decades?

This graph illustrates the low to high success rates by five performance areas within a railroad. Consider the numbers as relative accomplishments. The performance improvements covered:

- New network train routing and service pattern efficiency

- Interchange efficiency

- General & Administrative internal organization efficiency

- New customer profitability from diverted traffic or all new customers accepting single line newly added service.

Conclusions

A last wave of big company rail mergers isn’t inevitable – and is not even necessary. But it is possible if growth is the next strategic goal.

A merger (or mergers) could produce both a corporate benefit and an added geographic coverage public benefit.

Perhaps the biggest hurdle is this – well over half of global corporate mergers never achieve their major business objectives. There is plenty of research on mergers that failed.

It is also true that not every railroad merger was successful.

Yet if the current railroad freight business model has run its course and the growth plan is now to “milk” the network assets as market share diminishes, then a last round of mega-mergers might be a reasonable alternative.

A well-designed merger could assist the new railroad pivot towards more customer volume growth rather than margin growth.

As journalist Michael Blaszek wrote: “A merger of two or more big railroads would increase the combined carrier’s commercial breadth and scope and broaden the services it could offer. The fact that no single U.S.-based railroad reaches every important producing and consuming area of the country puts the industry at a competitive disadvantage to nationwide truckers.”

He also wrote, “Shippers want to deal with as few transportation providers as possible, as long as there is enough competition to keep freight rates in check.”

Success likely requires a merger application that demonstrates hard evidence of a competition benefit that shippers and the public will reap.

More stockholder benefits will not boost the deal in front of a skeptical STB regulatory body.

Proving the public benefit is not impossible. It will, however, be challenging.

Are the STB commissioners ready with their procompetitive metric examinations? That is not clear.

Before an application shows up at the STB offices, it’s probably timely now for regulators to consider the consequences of a continuing diminished railroad freight role.

One competition test is the realization that at some lower traffic mass, the railroads might become inconsequential save for a few strategic lanes.

Have regulators considered this outcome? Why wait? Why not research the possible outcomes now – ahead of the game? After all, mergers are clearly in the DNA of American railroading. The theory is that an application will show up at some point.

The suggestion is to lead the process now by taking a deep look into the STB’s railway waybill sample records. What does that database they already possess tell them if they look closely at the unfiltered origin and destination patterns?

The question of rail freight relevance mode competition shifts is within their intellectual grasp.

(Photo: Flickr/Peter Van den Bossche)

Here is the good news. A near-term announced big railroad merger scenario isn’t required because the railroads are financially weak. It’s because their limited access steel rails network coverage is lacking against the always/present everywhere asphalt and concrete truck ways.

When (and if) a railroad merger announcement is made, the biggest factor during the review process is likely to be fear. There will be both a corporate fear factor and a public policy fear factor.

The largest corporate fear factor is becoming the last network carrier possibly without a partner. Shippers and the public fears will focus on becoming a possible single carrier-served location or a location with inferior post-merger routes.

What will the network end game look like? Here’s one possible commercial service competitive outcome to hypothetically consider:

BNSF + NS + CP + KCS

UP + CSX + CN + Ferromex

First mover?

Railroad history suggests it might be a maverick. An unexpected company; perhaps not even a rail sector “insider.”

As a teaser, think of Ferromex Grupo México Transportes. Or perhaps someone that brings the larger logistics perspective like Berkshire Hathaway’s BNSF. Or someone who sees railroads as a “real estate” or private toll way/industrial park commerce play.

Here is a simplified strengths and weakness checklist.

What’s your view?

Recommended references for a deeper look:

- Frank N. Wilner – Railroad Mergers History Analysis Insight, 1997.

- Michael W. Blaszak – The Merger Puzzle: “Railroading has changed dramatically since the merger frenzy of the 1990s” – Trains, October 2014.