Since writing about the challenges ahead for food supply chains, I have been thinking about how perishable foods and other items are transported from one part of the world to another. What is the role for new technologies in global supply chains for perishable products? The question gnaws at me each time I am in the grocery store staring at produce that has travelled thousands of miles to get to retailers in the United States.

According to data from the USDA, between 1999 and 2017:

- Imports of meat to the United States grew at an average annual rate of 5.7%, from roughly $3.3 billion to about $8.9 billion.

- Imports of fish and shellfish grew at an average annual rate of 4.8%, from roughly $8.9 billion to about $21.3 billion.

- Imports of dairy grew at an average annual rate of 2.7%, from approximately $930 million to about $1.8 billion.

- Imports of vegetables grew at an average annual rate of 6.3%, from approximately $3.6 billion to about $12.7 billion.

- Imports of fruits grew at an average annual rate of 8.3%, from approximately $4.8 billion to about $18.4 billion.

As these food products traverse the food supply chain – from producers to processors to distributors to retailers and then finally to consumers – there is a complex set of regulations and requirements that govern how they are transported across the food value chain. These regulations focus on preventing and responding to foodborne illnesses.

A big problem, and a big opportunity

In an August 2018 report; Tackling the 1.6-Billion-Ton Food Loss and Waste Crisis, the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) concluded, “Each year, 1.6 billion tons of food worth about $1.2 trillion are lost or go to waste – one-third of the total amount of food produced globally. To put the figure in perspective, that is 10 times the mass of the island of Manhattan. And the problem is only growing; BCG estimates that by 2030 annual food loss and waste will hit 2.1 billion tons worth $1.5 trillion.”

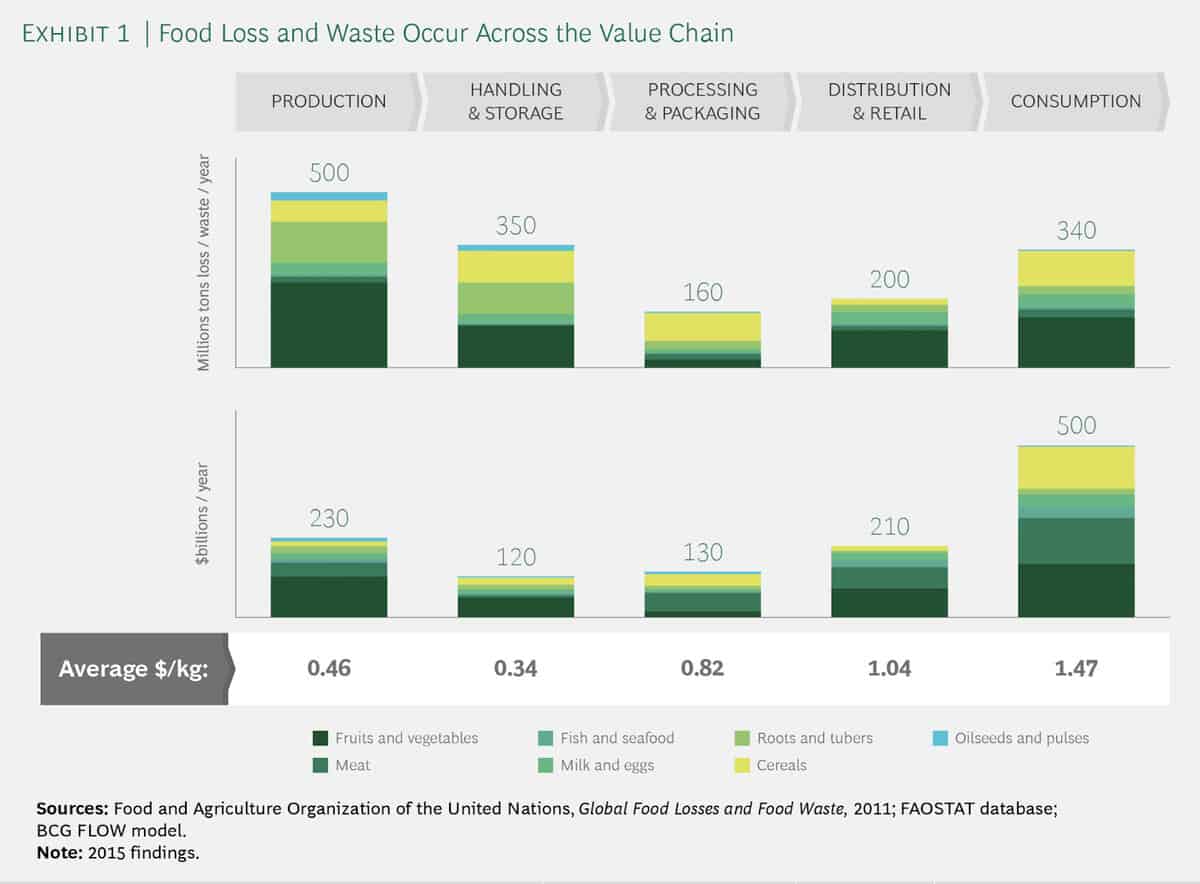

Additional data from the BCG study is available in the following two exhibits. The first exhibit shows where food loss and food waste are most severe across the value chain.

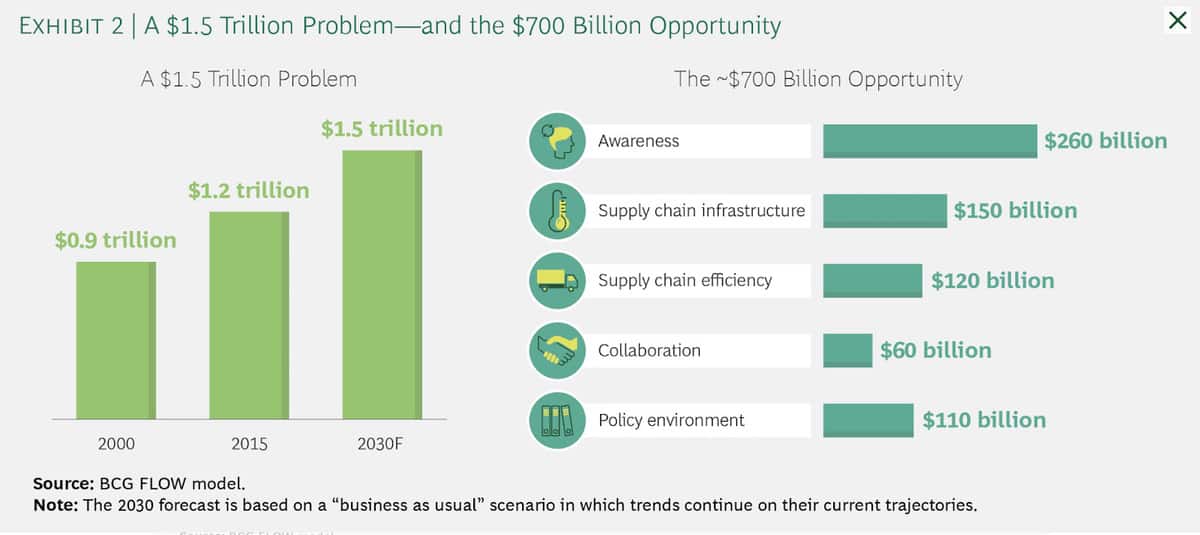

The second exhibit shows where, according to BCG’s analysis, there’s an opportunity for savings to be realized.

In Food Routes: Growing Bananas in Iceland and Other Tales from the Logistics of Eating, Robyn Metcalfe discusses four pillars that support food supply chains. They are:

- Reliability – because each stage of the value chain depends on the previous stage, reliability within food supply chains is an issue.

- Trust – As we have already seen, there are numerous rules and regulations that govern the production, processing, distribution and sale of food to consumers. This system of rules and regulations is meant to instill trust in consumers – trust that the food they are buying is safe to consume.

- Adaptability – When problems arise in the food supply chain, organizations within the value chain must be capable of reacting to ensure that there is no major disruption to the supply of food to consumers.

- Technology – This leads to the question stated at the outset – What opportunities exist for technology startups to develop innovations that enable the food industry to solve this problem using software, and other software-enabled technologies?

Looking at the second exhibit from BCG’s study, it would appear that supply chain infrastructure and supply chain efficiency hold the most promise for technology startups to introduce innovations into food supply chains. One issue that could pose a significant stumbling block is the degree of fragmentation within global food value chains.

Insights from the field

Amit Hasak is founder of Transship, a startup based in Chicago that is building an automated freight forwarding platform for perishable goods – food, pharmaceuticals, etc. Prior to launching Transship in 2017, Amit worked in his family’s cold storage business in Chicago, starting in 1999.

In Amit’s view, “Automation is the name of the game. The food supply chain in particular relies very heavily on manual labor. Freight forwarding for example is basically done the same today as it has been for decades when arranging international shipments. Needless and time-consuming telephone calls, emails and even faxes. This leads to inefficiencies that affect the food supply chain and also sustains the high cost of shipping. By introducing technologies such as application programming interface, blockchain and real-time tracking, startups such as Transship help reduce the cost of shipping, increase efficiency and introduce visibility. As a result, there is less food waste, the cost of food will be reduced and companies can invest more in business development rather than logistics.

Conclusion

It would be a mistake to assume that the $700 billion opportunity identified in the BCG study is one that is wholly available to technology startups. For startup founders and investors looking at this market, a more granular analysis makes the most sense – How many potential customers exist? How much would these customers pay for a product or platform that improves critical supply chain information infrastructure and also increases supply chain efficiency? What other related problems could software startups solve?

Whichever software startups can build products that solve problems in global food supply chains in a way that gains quick adoption by the industry will do well. After all, it’s not as if people are going to stop eating food anytime in the near future.