Everything’s connected in ocean shipping. Very high demand for ships in one segment can affect supply-demand fundamentals for entirely different vessel types.

It’s happening now. Container shipping is so strong that reverberations are being felt in dry bulk. Spillover effects are boosting dry bulk fundamentals just as demand for traditional cargoes is rising. Spot rates for all bulker size categories have not been this high since the late 2000s.

“Dry bulk shipping has had the best start to a year in over a decade,” affirmed John Wobensmith, CEO of Genco Shipping & Trading (NYSE: GNK), on his company’s conference call with analysts.

Transmission between segments

Market effects are transmitted from one shipping segment to another in three main ways.

First, if a ship switches cargo types, such as when coated tankers toggle back and forth between products and crude. (Switching cargoes was more common in the past due to bulk-liquid combination carriers and conversions of older tankers into bulkers.)

Second, if a cargo switches ship types, such as in the mid-2000s, when dry bulk charter rates rose so high that grain shippers switched more exports to containers.

And third — by far the most important transmitter — if Asian shipyards fill up. The most extreme example was the shipping super-cycle of 2003-2008. Demand for new container ships, bulkers, tankers and gas carriers simultaneously surged. Each ship type competed with the others for yard slots, jacking up newbuild costs for everyone.

The second and third categories of spillovers are emerging in the current market.

Container cargo starting to move in bulkers

During Friday’s call with analysts, Eagle Bulk (NASDAQ: EGLE) CEO Gary Vogel said Supramax bulkers (vessels with a capacity of 45,000-60,000 deadweight tons or DWT) are starting to benefit from “spillover trades typically carried on container ships.”

“For example, we’ve recently carried cargoes such as bagged cement from China to Guatemala and bagged fertilizer to Peru and Chile. While the Pacific loading is typically a fronthaul market for container ships, these trades represent backhaul routes in dry bulk.” The more backhaul volume, the better the round-trip utilization.

“It’s definitely meaningful,” said Vogel of the container-shipping spillover.

“It’s sustainable as long as we see this dislocation in the container market. How long that goes on is not really our area. But I am an interested reader of everything that comes out of the container world right now because it is having a profound effect on both our rates and our trading patterns.”

Container orders blocking bulker orders

During this week’s conference call of crude-tanker owner Euronav (NYSE: EURN), CEO Hugo De Stoop said that orders for new container ships and liquefied natural gas (LNG) carriers are sharply limiting the ability to over-order tankers.

Dry bulk executives made the same point. “There is a scarcity of building capacity at most shipyards,” Safe Bulkers (NYSE: SB) President Loukas Bomparis told analysts. “The slots are being filled by other sectors such as containers and tankers.”

According to Vogel, the dry bulk orderbook is at a historic low, with tonnage on order representing just 5.6% of the on-the-water fleet. New orders in Q1 2021 were 33% lower than the quarterly average in full-year 2020.

Pricing has “increased meaningfully,” with yards now seeking $27 million-$29 million for Ultramaxes (bulkers with capacity of 60,000-65,000 DWT) for deliveries no earlier than mid-2023.

“Prices have increased due to rising costs of inputs including steel and also due to a lack of shipyard capacity,” he said.

Shipyard capacity has “shrunk quickly due to the pace of ordering in other shipping segments. Orders for large container ships hit a record over the past few months. Combined with orders for other large and complex vessels such as VLCCs [very large crude carriers], this has helped fill the yards’ orderbooks with ships that take considerably longer to construct and that are typically more attractive for yards to build [than bulkers].”

A look back to mid-2000s

The container shipping industry is now in the midst of a boom on par with the mid-2000s super-cycle. What made the earlier era different was that all of the shipping segments hit rate highs at once due to simultaneous spikes in demand, largely driven by China, with that demand simultaneously outpacing vessel supply across the board.

From the January 2005 IPO prospectus of DryShips, a company that delisted in 2019: “The shipping industry is in an unusual position. Each of its major sectors — dry bulk carriers, tankers and container ships — has been prospering. This has helped trigger an upsurge in newbuilding activity across each of these fleet sectors. Newbuilding demand is also strong for LNG carriers and other specialized ship categories.

“The significance of this is that the near-term availability of newbuilding berths for vessel delivery for before Q3 2007 and Q4 2007 [two and a half years after the IPO] is scarce. The result is that the value of secondhand vessels has increased significantly. Newbuilding prices for all vessel types have increased significantly, due to a combination of rising demand, shortage in berth space and rising raw material costs, especially steel.”

Some of that history is starting to sound a little familiar, but the current dynamic is nowhere near that of the mid-2000s, except in container shipping. Asset pricing and rates are up are up in dry bulk, but nowhere near super-cycle highs. Tanker markets are facing their worst depression in three decades. On the global demand front, a full-scale post-COVID recovery remains hypothetical.

Nevertheless, even a small echo of the super-boom of the mid-2000s — the scarce newbuilding slots and rising cross-segment spillover — is a positive sign.

Dry bulk earnings roundup

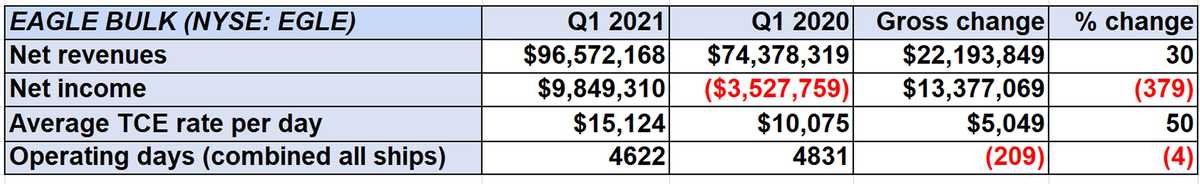

On Thursday, Eagle Bulk reported net income of $9.8 million for Q1 2021 compared to a net loss of $3.5 million in Q1 2020. Adjusted earnings per share (EPS) of 90 cents came in above the consensus estimate for 72 cents.

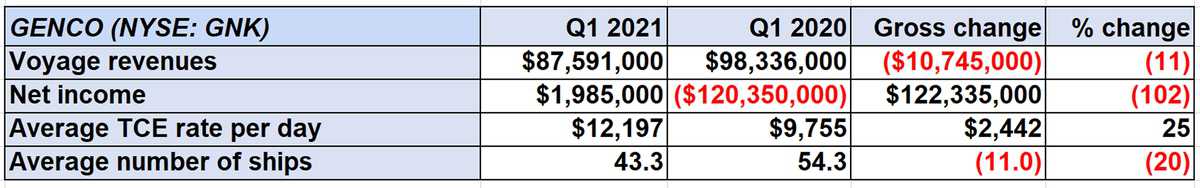

On Wednesday, Genco reported net income of $2 million for Q1 2021 compared to a net loss of $120.4 million in Q1 2020. Adjusted EPS of 6 cents compared to analyst expectations for 3 cents.

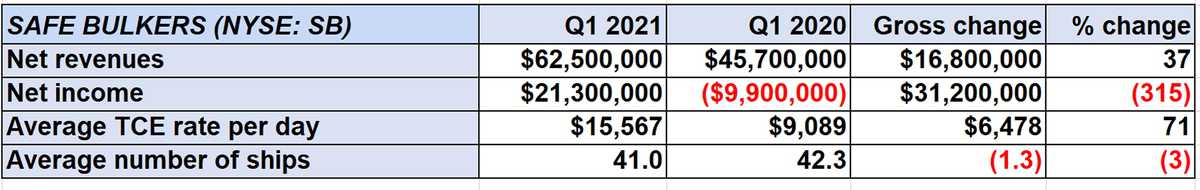

Safe Bulkers reported net income of $21.3 million for Q1 2021 versus a net loss of $9.9 million in the same period last year. Adjusted EPS of 14 cents topped the consensus forecast for 11 cents.

Click for more articles by Greg Miller