[vimeo-autoplay video-id=”396472883″]

The degree of uncertainty within the U.S. container shipping industry is now verging on the surreal.

There’s the fallout from the Chinese factory shutdown, unknown consumer demand effects from the coronavirus, volatile fuel costs due to the IMO 2020 regulation, high debt levels among carriers, a collapsing stock market, and to top it all off, the trade war isn’t over yet.

To better understand how these issues could impact U.S. shippers of containerized cargo and their ocean carriers, FreightWaves interviewed Jim Blaeser, a director in the transportation and infrastructure practice of global consultancy AlixPartners.

Coronavirus and contract season

“How can you negotiate a contract with all this uncertainty?” wondered Blaeser, who pointed out that talks between carriers and shippers on annual contracts often begin at the TPM conference in Long Beach, California — an event that was just cancelled due to coronavirus. “It really says something that we can’t even get together to start figuring this out.

“It’s going to be a wild year. I don’t know how you can set a price today between a shipper and a carrier for a 12-month contract that anybody can feel they have any certainty on.

“Typically, if the market is pretty clear and frankly, if it is favorable to the shippers, the shippers will contract early,” he explained. “They’ll get contracts done in April. If they’re not certain, they may not finalize contracts until June. This year, I can’t imagine that anything will get settled until late May or early June — and a lot can happen between now and then.”

That timetable implies some of the uncertainty around coronavirus and other issues will clear up in the next few months. “If the world continues to become increasingly uncertain, then all bets are off and we’d start to enter the territory where we’re shipping off-contract.

“But even so, if you’re a mega-shipper, your freight is still going to move. It’s just a matter of with whom and what you’re paying. It’s not like the world ends in a stalemate if you don’t have a signed piece of paper. And it’s not like it would be totally unheard of. There is a spot market on the trans-Pacific and most of the European trades work on more of a spot-market basis anyway.”

A pivotal timing question is: When will a return to normalcy for the Chinese export system lead to a catch-up period of increased freight demand? When that happens, the carriers would want to be in position to charge higher rates to compensate themselves for what they’ve lost. “If you lose several weeks in a 52-week cycle, it’s significant,” said Blaeser. “Shippers are going to be desperate to get their cargo moving and get their inventory levels back to where they need them and carriers will need to be opportunistic to recover their profitability for the year.”

There is increasing confidence that Chinese factories and transport systems are normalizing, but this headwind is being supplanted by demand risks in consuming nations such as the U.S. as the virus spreads. “The more this [coronavirus] takes root here, the more we’re trading one problem for a different problem,” said Blaeser.

IMO 2020

The disappearance of IMO 2020 from the headlines shows just how overwhelming the coronavirus issue has become. IMO 2020 requires all vessels without exhaust-gas scrubbers to switch from cheaper 3.5% sulfur heavy fuel oil (HFO) to more expensive 0.5% sulfur fuel known as very low sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO).

Coming into this year, the IMO 2020 regulation was trumpeted as an existential threat to container lines, on the premise that they would go bankrupt if they did not successfully pass the added cost of VLSFO along to shippers.

So far, it hasn’t turned out as predicted. According to data from Ship & Bunker, the average VLSFO price at the world’s top four bunkering hubs was down to $434.50 per ton on Thursday. A year ago, the average price for HFO at those hubs was $429.50 per ton.

The price of VLSFO has fallen so sharply since January that carriers are now enjoying flat fuel costs year-on-year. And with the price of crude plummeting in the wake of Friday’s failed OPEC negotiations, carriers could soon be paying less for fuel than they did a year ago, despite IMO 2020.

Nevertheless, Blaeser believes IMO 2020 could have lasting implications in terms of how carriers charge shippers for fuel. “In our view, carriers have been using surcharges even before IMO 2020 to effectively pass along fuel costs — and then some. We believe they were making a profit [on surcharges] before and that they’re making a profit now.

“But fuel has really become center stage for the freight industry this year and the question is: Will the shipper community continue to permit carriers to charge for fuel in this very opaque and fragmented manner? When you think about how the mega-shippers — the Walmarts and Targets — have driven the uniformity of trans-Pacific contracting practices over the years, it’s not out of the realm of possibility that the next frontier will be the shippers driving uniformity and transparency with fuel. That is a real risk to carrier profitability.”

Carrier financial health

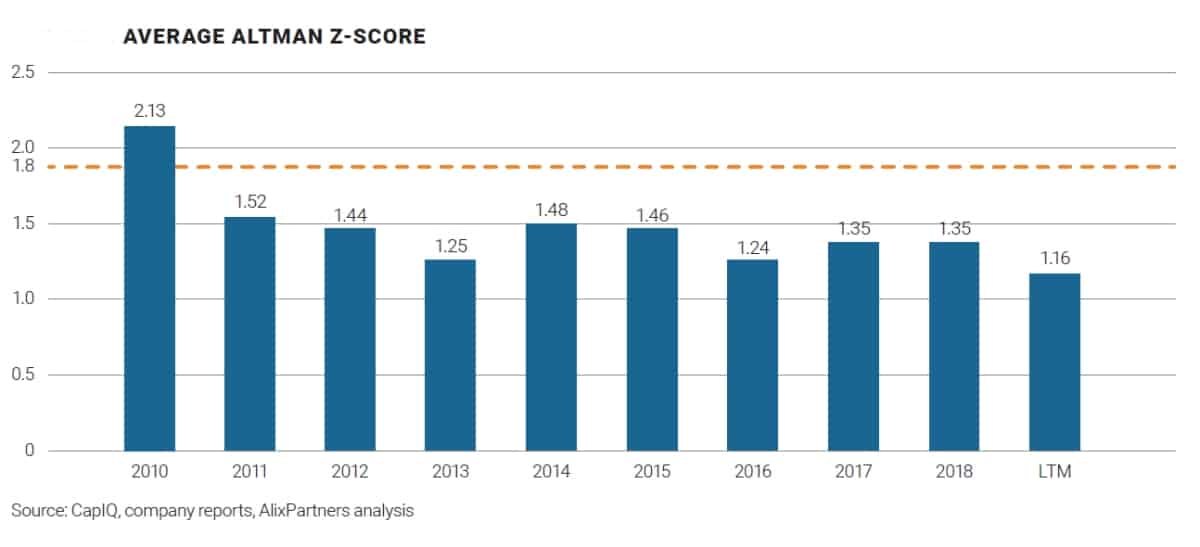

AlixPartners released its annual outlook on the container sector earlier this month. One section of the report that’s garnering attention features the average Altman-Z scores of 14 carriers that publicly release financial results. Altman-Z is a metric measuring the likelihood of the carriers seeking bankruptcy in the next two years; a score of 1.8 or lower is considered “high risk.”

AlixPartners found that the carriers’ average score in 2019 was at its worst level in a decade, implying that “any financial shocks in the coming months could shift some carriers’ finances from worrisome to downright distressed.”

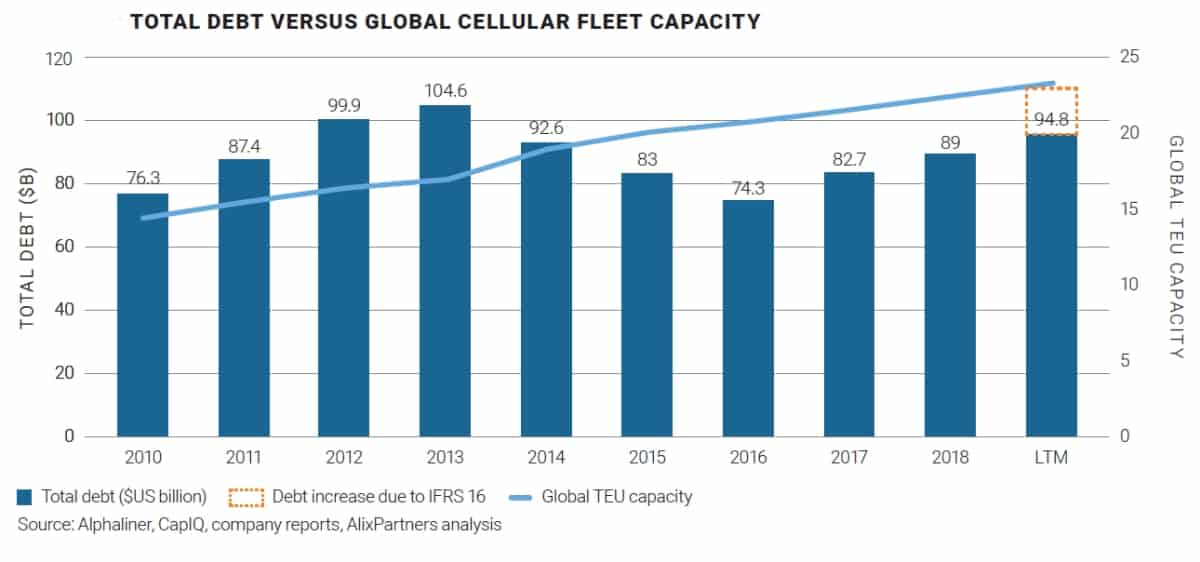

Blaeser put this data in context when speaking with FreightWaves. Debt levels remain very high, at $94.8 billion in 2019 (excluding leases reclassified as debt due to new accounting rules), up 28% from 2016 levels.

When debt previously peaked in 2013 at $104.6 billion, Blaeser explained that liabilities were driven up capital investments in fleets — “newbuilding orders during a period where there was an arms race towards bigger and bigger ships.”

The latest peak has a different driver: consolidation. “These deals were not financed using all cash and stock; a lot of it was financed with debt. So, the debt burden is not just from the fleet investment cycle, it’s also from the consolidation cycle.”

High debt mixed with the coronavirus sounds like a particularly dangerous cocktail, but there’s at least one factor that could stave off carrier failures. “Some of these carriers are outwardly nationally sponsored, and in some cases it’s a bit more behind the scenes,” said Blaeser. “This has always been the case and national sponsorship has given carriers a few extra lives beyond what their finances would suggest.

“I don’t want anyone to read our Altman-Z scores and say, ‘Somebody’s about to go out of business.’ We’re just highlighting that the risks are there. I don’t think one of the majors will go under. Actually, I think that’s highly unlikely due to national sponsorship and other factors.”

For larger carriers, the more likely outcome would be “significant reorganization and a shuffling of what they look like in terms of the markets they service and the service levels they offer.” The 2020 insolvency threat is much higher for the smaller players. “The smaller and more niche carriers face a greater risk of distress and failure,” warned Blaeser. More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller