The implementation of the IMO 2020 marine-fuel regulation has gone completely off script.

Marine-fuel pricing has actually fallen year-on-year and the predicted savings from exhaust-gas scrubbers have increasingly evaporated. What happened and what’s next?

The IMO 2020 rule, effective Jan. 1, requires all ships that do not have exhaust-gas scrubbers to burn either 0.5% sulfur fuel known as very low sulfur fuel oil (VLSFO) or 0.1% sulfur marine gasoil (MGO). Ships with scrubbers can continue to burn 3.5% sulfur heavy fuel oil (HFO).

Declining fuel spread

Scrubbers worked like a charm earlier in the first quarter because VLSFO was much more expensive than HFO.

In bulk shipping, a time-charter-equivalent (TCE) rate for a spot contract is calculated by taking the spot rate in dollars per ton of cargo and converting it to dollars per day, subtracting voyage costs including fuel. Consequently, if the price of VLSFO is much higher than that of HFO, a scrubber-equipped ship burning HFO earns a much higher TCE rate for the same spot contract than a non-scrubber ship, due to fuel savings.

In early January, a scrubber-equipped VLCC (very large crude carrier; a tanker that can carry 2 million barrels of crude oil) was netting $25,000 per day more in TCE earnings than a non-scrubber ship. A scrubber-equipped Capesize bulker (with a capacity of around 180,000 deadweight tons or DWT) was earning $10,000 a day more than a non-scrubber Cape.

On Jan. 6, the VLSFO-HFO spread peaked at around $350 per ton. A large container ship with a capacity of 10,000 twenty-foot-equivalent units or more, sailing at 16 knots, would burn about 100 tons of fuel per day — meaning that such a ship, if it had a scrubber, was saving $35,000 per day.

All that has changed. On Tuesday, in the wake of the historic 24% slide in the price of crude the previous day, “quotes for compliant fuel [VLSFO] out of Singapore, Rotterdam and Fujairah [were] falling close to 20% on the day,” said Clarksons analyst Frode Mørkedal. “HFO bunker fuel has not seen the same moves. This has made fuel spreads non-existent on the day, with scrubber premiums closing in on zero.”

Clarksons estimates scrubber savings are down to just $1,400 per day for Capesizes and $1,200 per day for VLCCs. These represent declines from January highs of 86% and 95%, respectively.

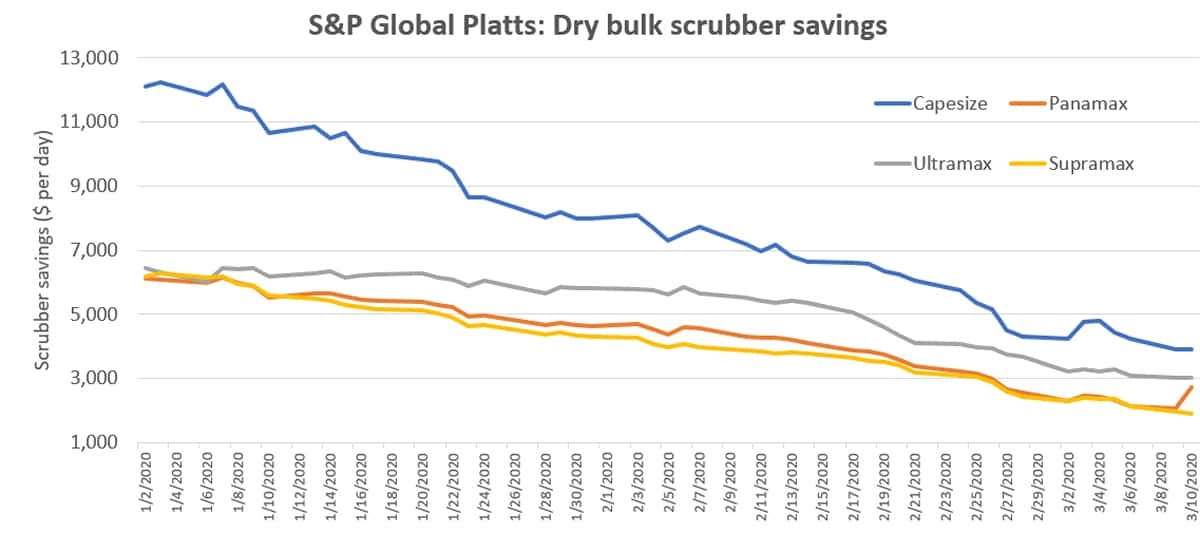

S&P Global Platts began tracking the spread between scrubber-equipped and non-scrubber Capesizes (reference size: 181,000 DWT) in late 2019, via its dual CapeT4 indices. In addition, it has provided FreightWaves with scrubber-savings estimates for three smaller bulker classes: Panamaxes (reference size: 81,000 DWT), Ultramaxes (63,000 DWT) and Supramaxes (57,000 DWT).

While Platts estimates a higher current Capesize scrubber savings than Clarksons, the trend in the Platts data looks the same. From January highs through this Tuesday, Capesize scrubber savings estimated by Platts are down 68%, for Panamaxes down 65%, Ultramaxes 53% and Supramaxes 70%.

Not only are savings from scrubbers being squeezed, one of the rationales for installing scrubbers in the first place — to protect against a higher fuel bill — has been undercut. Ship owners are now paying less for IMO 2020-compliant VLSFO than they did for more polluting HFO one year ago.

The average price for VLSFO in the world’s top four bunkering hubs was $352 per ton on Monday, according to Ship & Bunker. One year prior, the average price of HFO in those hubs was $428 per ton, equating to a year-on-year savings of 18% for non-scrubber ships.

According to Alan Murphy, CEO of Sea-Intelligence, a research firm focused on the container sector, “Two months ago, IMO 2020 was set to be the carriers’ major problematic issue. Today, low-sulfur fuel prices are dipping below the levels for normal fuel last year.” Murphy believes marine fuel has the potential to fall even further, “to levels seen in 2015-16,” rendering “the cost of low-sulfur fuel the least of the carriers’ problems.”

What happened?

The reason for the plunge in scrubber savings is the coronavirus and its effect on global crude pricing, which initially fell due to expectations for decreased demand in China as a result of the Wuhan quarantine and post-Chinese New Year shutdown. Pressure on crude continued to mount as likely demand effects became apparent in Italy, South Korea and now the U.S. The coronavirus then precipitated a dispute between Saudi Arabia and Russia, threatening a price war that has brought crude down further still.

The price of VLSFO has fallen in parallel with the price of crude, but the price of HFO has held up better, squeezing the spread.

In 2019, there were two theories on why the VLSFO-HFO spread would be high and scrubbers would be profitable: Either HFO would stay the same and VLSFO pricing would surge, or alternatively, VLSFO would be on par with where HFO used to be, but the price of HFO would collapse due to a lack of demand. So far, neither has proved correct. VLSFO did indeed surge, but it fell back quickly, and HFO has not collapsed.

On the VLSFO side of the equation, shipowners prepurchased a significant stockpile prior to IMO 2020 implementation, both to protect themselves against price spikes and to ensure quality. A Morgan Stanley research note on Monday pointed out that “the amount of compliant fuel inventory built up in late 2019 created an overhang” and “companies have been producing more VLSFO than initially expected.”

On the HFO side of the equation, the volume not consumed by scrubber-equipped ships must be refined into another product, sold for asphalt production, or used as fuel in less-regulated countries. In 2019, there were dire warnings that there would be so much excess HFO that land-based storage would be overwhelmed and it would have to be stored on tankers.

That didn’t happen. Asphalt pricing has been surprisingly strong due to new infrastructure projects, and more importantly, certain refiners retooled their systems to process more HFO.

During the quarterly call of crude-tanker owner Euronav (NYSE: EURN) on Jan. 29, the company’s head of fuel procurement, Rustin Edwards, explained, “The U.S. Gulf Coast refining system retooled in the third quarter to bring in high-sulfur fuel for full destruction, increasing coke utilization. The Indian refining sector also played a part, ramping up the refining of high-sulfur fuel oil. So in the end, the Russian refining system, which is long high-sulfur fuel oil, found a home for the fuel that they produced and has been shipping large parcels into the U.S. Gulf Coast, and the Middle East refiners long high-sulfur fuel also found a taker in the Indian refiners for the residual that was not going to be consumed by the scrubber-fitted vessels.”

What’s next?

It’s possible that the narrowing of the VLSFO-HFO spread is a temporary anomaly. VLSFO demand could rise after the inventory that built up prior to Jan. 1 is worked through, and as the Chinese supply chain comes back online and cargo volumes increase. Saudi Arabia and Russia could resume talks and the price of crude could revert (Brent rose 9% on Tuesday). And once the coronavirus is globally contained, economic activity would normalize, and oil prices (and assumedly VLSFO prices) would increase further.

That said, the extreme narrowing of the spread less than three months after IMO 2020 implementation could give ship owners pause about ordering new scrubbers, and could give investors pause about awarding a valuation premium to shipowners that buy scrubbers.

The first wave of scrubber installations is taking much longer than expected due to coronavirus-induced yard delays in China; it will extend throughout this year. The second wave of installations may be less likely given recent events. Morgan Stanley cited a scrubber manufacturer who said a VLSFO-HFO spread of $100 per ton was the “tipping point” where owners make the scrubber-installation decision. If so, the spread has just dipped below that tipping point.

Meanwhile, the jury’s still out on share-price upside from scrubbers. Scrubbers have bolstered first-quarter returns for tanker owners, but share pricing is down due to coronavirus (even including the rebound for crude-tanker stocks in recent days).

For dry bulk, scrubbers have allowed owners to break even and avoid steep losses, but stock investors have little interest in dry bulk, given extremely depressed market conditions. A scrubber-centric bulk owner may be the “best house in a bad neighborhood,” but stock investors can simply opt to place their bets on a better neighborhood.

Public shipping companies have invested huge sums in scrubber installations. Star Bulk (NYSE: SBLK) has invested $209 million to put scrubbers on 109 ships. But the real cost of installing scrubbers is much higher when opportunity costs are included. Numerous public shipping companies reported weak fourth-quarter results due to out-of-service time for scrubber installations (which are taking 30-60 days apiece) as well the acceptance of below-market rates on voyages used to reposition vessels to the shipyards for those installations.

The “payback period” for massive scrubber investments is calculated via the savings per day, which is based on the VLSFO-HFO spread. Given what’s going on now, and how the fuel spread is being compressed by the coronavirus, payback periods look like they could be longer than anticipated. More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller