Will enough containers get where they need to be? It’s a crucial question for the world’s ocean shipping network — a question that’s increasingly difficult to answer given how nebulous demand has become.

A shortfall of containers means cargo can’t move. At the same time, repositioning empties fills up ship slots and creates pricing pressure for full containers on the same vessels.

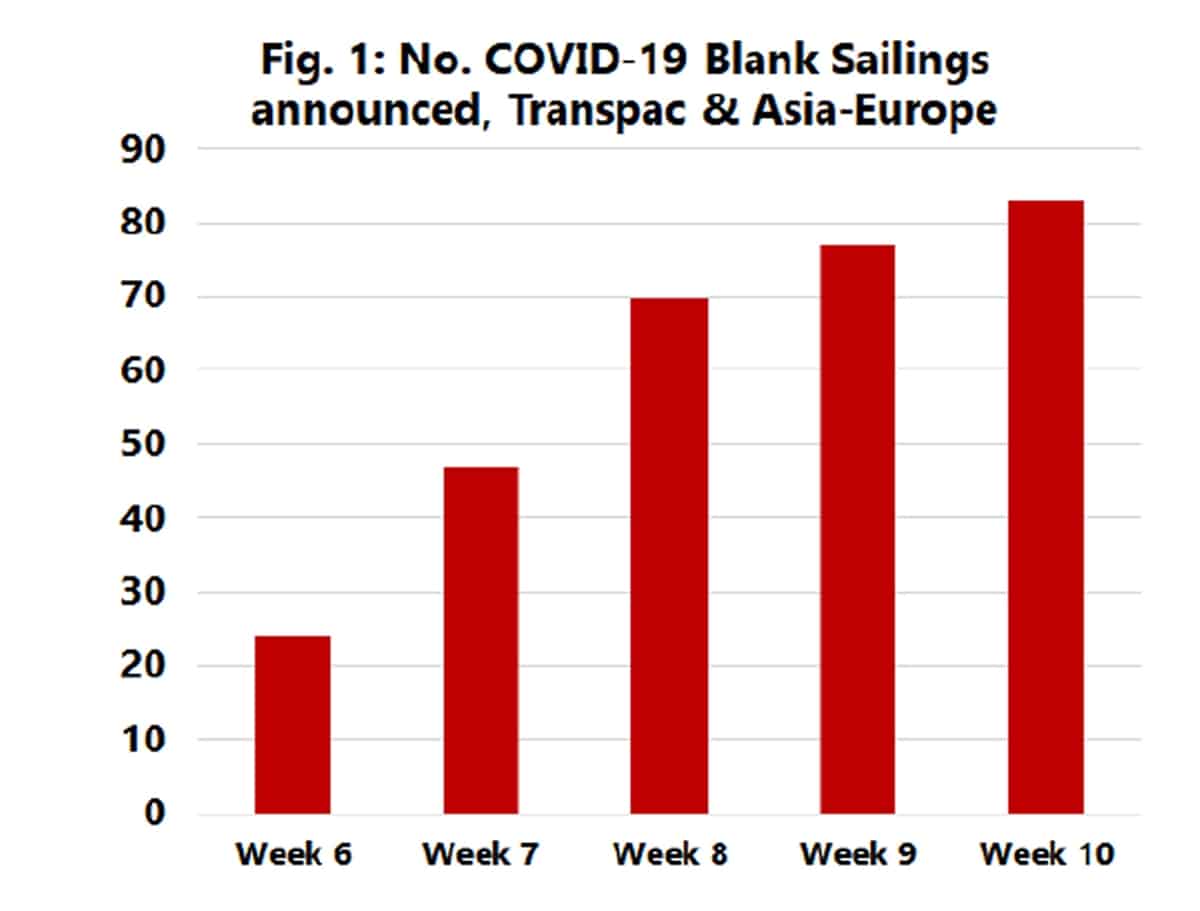

The empty-repositioning challenge was created by the enormous number of blanked (canceled) sailings from China to the U.S. and Europe in the weeks following Chinese New Year, when the coronavirus outbreak brought Chinese exports to a near standstill.

Normally, container ships bring loaded containers on headhaul runs to the U.S. and Europe. The boxes are emptied and then used for backhaul export cargoes from the U.S. and Europe.

The blanked sailings slashed the number of boxes arriving on headhaul routes, and at the same time, impaired the ability to return empties via the backhaul routes.

Box repositioning and freight rates

Alan Murphy, CEO and founder of Copenhagen-based Sea-Intelligence, told FreightWaves, “With the blanking of sailings due to headhaul volume shortfalls, there are a lot of containers in destination regions that will not get their intended return trip back to Asia, either laden with backhaul cargo or for empty repatriation.”

Problems caused by the lower number of empties returned to Asia “will be somewhat balanced by the fact that a lot of headhaul cargo did not move, leaving empty containers in Asia that are ready to go now,” Murphy explained.

“If we see a pickup in demand [for Asian exports], stocks [of empties] will be drawn down and the carriers will try to get the backlogs in destination regions back to Asia,” he continued.

In general, he said, “when we have equipment shortages, carriers usually focus on empty repositioning over backhaul cargo” given that “the premium for backhaul cargo is very low.” This dynamic can “lead to massive spikes in backhaul rates.” In other words, backhaul cargo moving from Europe to Asia, for example, would compete for space on ships with empty containers — and the cost to ship those backhaul cargoes would increase.

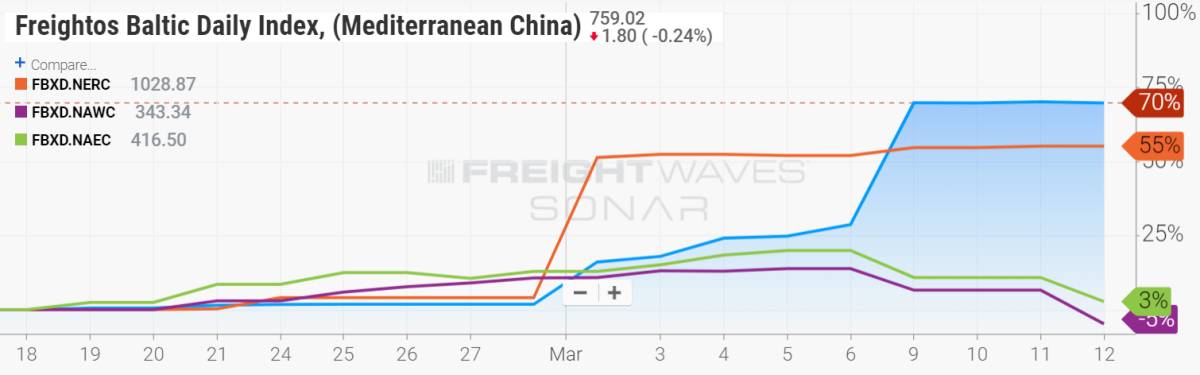

This cost rise is already apparent in the daily indices compiled by Freightos, which track the price to ship a forty-foot-equivalent unit (FEU) container. The rate from Northern Europe to China (SONAR: FBXD.NAEC) is up 55% since Feb. 18, and the rate from the Mediterranean to China (SONAR: FBXD.MEDC) is up 70% (rates from the U.S. have not materially increased).

At the same time empties are being brought back to Asia, Alphaliner is citing efforts in the trans-Pacific market to bring empty boxes in the other direction: from Asia to the U.S. West Coast ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach.

Alphaliner reported that Mediterranean Shipping Co. (MSC) is deploying some of its Megamax-class vessels — which have capacity to carry 19,000 or more twenty-foot-equivalent units (TEU) — into the trans-Pacific for the first time due to “the carrier’s need to address equipment shortages in North America.”

According to Alphaliner, “Since fronthaul cargo volumes have collapsed and only relatively few containers from China arrive in Europe and America with cargo, there is currently not enough container equipment to accommodate European and American export cargo.”

MSC, which usually deploys 13,000 TEU ships in the trans-Pacific as part of the 2M alliance with Maersk Line, is now deploying the 23,756-TEU MSC Mia (the world’s largest box ship), the 23,656-TEU MSC Nela, 19,224-TEU MSCO Oscar and 19,368-TEU MSC Anna.

Alphaliner believes that “the ad hoc deployment of Megamaxes will allow the shipping lines to carry a typical service load and at least an additional 6,000 TEU worth of empty containers to America.”

Containerized cargo demand

The container-repositioning equation hinges on how quickly Asian manufacturing gets back to normal on one hand, and how import demand in Europe and the U.S. is affected by coronavirus on the other.

“The industry not only has to worry about the supply of goods coming out of China, but also about possible drops in demand for those goods in the countries just starting to cope with the epidemic,” said Eytan Buchman, chief marketing officer of Freightos.

The good news is that the number of blanked sailings is declining. According to Murphy, “The weekly measure of carriers’ blank sailings out of China shows that the coronavirus impact is now subsiding rapidly. This means that carriers are seeing demand ramping up back to normal levels over the next few weeks.”

Buchman noted that “one interesting sign that production is picking up is the spike in intra-Asia air-cargo rates, indicating that Chinese factories are restocking the components they need to manufacture the backlog of orders caused by the shutdown.”

He continued, “Carriers are getting ready for a return of demand in the near future and a possible surge in late April.”

The planning conundrum for container lines stems from the giant variable on the demand side. Europe and the U.S. face potentially extreme demand destruction due to coronavirus.

Lars Jensen, CEO of Copenhagen-based SeaIntelligence Consulting (a different company than Sea-Intelligence) addressed the issue in a series of online posts.

Jensen wrote that “until now, the focus has been on the shortfall of cargo from China” but “the next effect we will see” is “due to the virus impact in Europe and the U.S., the import demand will drop sharply.” As a result, he believes that “the expectation of a surge out of China to make up for the earlier shortfall will be postponed.”

Jensen said that “the situation is unprecedented” but “there is one clear comparison: the financial crisis in 2008,” when global container volumes dropped by 10%. If the same contraction rate occurs this year, “this equals a decline of 17 million TEU globally for container lines” and ports and terminals could “potentially be looking at a loss of 80 million TEU of handling volume,” he warned. More FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller

joseph n. graif

are you aware that a viable solution to the problem of re-positioning empty containers, invented right here in the united states, has existed for over ten years? despite earning multiple patents and passing csc testing, the solution has been ignored by the industry and failed to attract any investment. why??

Mary Walls

Most container yards are overflowing with equipment but the SSL all claim to have no empties.

Anyone else find all of this peculiar?