Sanctions and a currency crisis are adding to instability in Iran

On Sunday in the southern Iranian cities of Khorramshahr and Abadan, a clash between demonstrators and police turned violent when the security forces put down the protest with gunfire. Iranian state news agency IRNA sought to downplay the unrest, claiming that only one person, a police officer, was injured, but the Washington Post is reporting that at least 11 people sustained injuries. ZeroHedge published a roundup of videos of the protests uploaded to social media that appeared to show that both sides were armed.

Rudy Giuliani was in France speaking before the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), an umbrella organization for exiled opponents of the Ayatollah’s clerical rule in Iran, and said in a Reuters interview that “I can’t speak for the president, but it sure sounds like he doesn’t think there is much of a chance of a change in behavior unless there is a change in people and philosophy.”

There are two external factors outside of Tehran’s control contributing to instability in the country. The first is a decade-long drought that has made potable water scarce in several areas in southern Iran, the region most severely affected by the drought.

“Over 90% of the country’s population and economic production are located in areas of high or very high water stress. This is two to three times the global average in percentage terms, and, in absolute numbers, it represents more people and more production at risk than any other country in the Middle East and North Africa,” Claudia Sadoff, director general of the International Water Management Institute, told Al-Monitor in March.

The days of protests in Khorramshahr came after residents complained of muddy, salty water coming from their taps. This isn’t the first time that water crises have inflamed sociopolitical instability in the Middle East: Syria’s instability prior to its civil war in 2011 was partly due to its overcrowded cities, whose populations had been swelled by up to 1.5M rural farmers fleeing drought-caused crop failures.

The second external factor is the effect of the United States’ renewed sanctions on Iran, part of President Trump’s decision to pull out of the Iran nuclear deal. The Iran rial has fallen to 42,605 against one US dollar on the official markets, but trades at about half that value inside Iran. Last week, Iran banned more than 1,300 imported goods that the government says it can produce inside the country, including home appliances, textile products, footwear, furniture, healthcare products, and some machinery. The import bans mark a resumption of Iran’s ‘resistance economy’, initially declared in 2012 as a strategy to promote Iranian self-reliance in the face of Western sanctions. That policy had been eased in 2016 after the nuclear deal was struck, and Iran was starting to let more foreign investment into the country.

Merchants in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar were on strike last week, protesting the deterioration of the Iranian rial, recession, and rising prices.

OPEC has struggled to deal with the collapse of Venezuelan oil production, reaching an agreement in principle that production among member states should be increased, without saying by how much or by who. If the United States is able to persuade the international community to shun Iranian oil and exclude it from the world markets, or if the rial loses its value as steeply as the Venezuelan bolivar and oil workers can no longer be paid, the shock to the world oil supply would be even greater. The Venezuelan state oil company, PDVSA, was contractually obligated to export about 1.5M barrels per day to its customers in the month of June, but fell well short of that, only making available about 694K bpd.

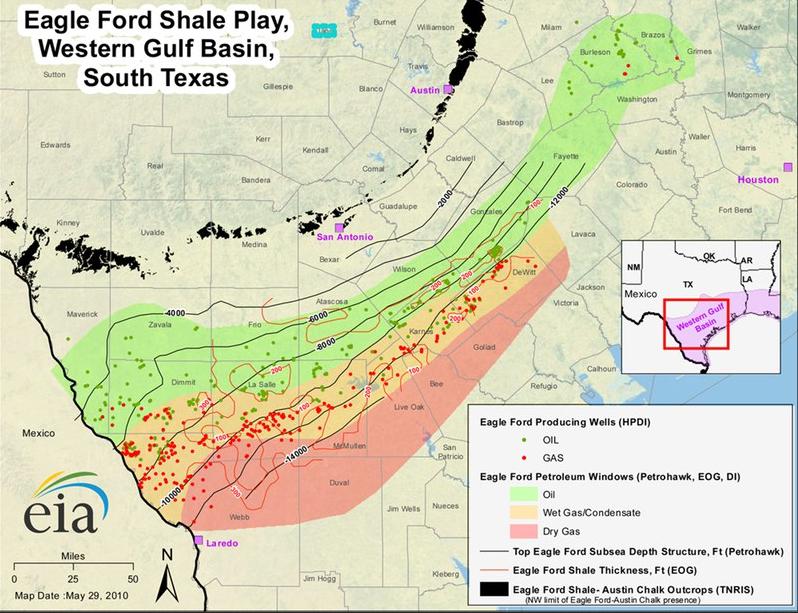

Iran, on the other hand, maintained a daily export rate of 2.13M bpd for 2017—a failure of its oil economy would be of an even greater magnitude, and would spike the price of Brent crude and potentially widening the Brent-WTI spread. A wider Brent-WTI spread means that American oil (West Texas Intermediate) would trade at a larger discount to the internationally benchmarked oil, potentially spurring increased production in areas like the Eagle Ford shale play, which still have not maxed out their takeaway pipeline capacity. The Eagle Ford stretches upward in a northeast direction from the Mexican border just north of Laredo up under San Antonio and comes to an end between Dallas and Houston:

President Trump said that he asked Saudi Arabia to produce an extra 2M bpd to offset the effect of sanctions against Iran, but Saudi officials have not indicated that a formal agreement was reached. For now, Iran’s oil production is threatened by significant geopolitical risk that may grow more acute if President Rouhani fails to find a way out of the country’s economic crisis.

Stay up-to-date with the latest commentary and insights on FreightTech and the impact to the markets by subscribing.