Pandemic, hurricanes, wildfires, social upheaval, geopolitical and financial crises, swarming locusts, an exploding port … 2020 has been a biblically ominous year. And it’s only September.

U.S. importers are realizing that supply chains must change. They must have more resiliency. Because this year is almost certainly not a one-off. As the philosopher Jacques Derrida put it, “The end approaches, but the apocalypse is long-lived.”

The effect of trade shocks is the focus of a new report by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI), “Risk, Resilience and Rebalancing in Global Value Chains.” To find out more about how this issue will shape the future of ocean freight, FreightWaves interviewed one of the report’s authors, McKinsey partner Ed Barriball.

“Everyone built these global value chains under a set of assumptions about what the world looked like and the probabilities of different events,” Barriball told FreightWaves. “Now, everyone is finding out that some of those assumptions weren’t right. That it’s time to reassess what the next five or 10 years will look like.”

More shocks are coming

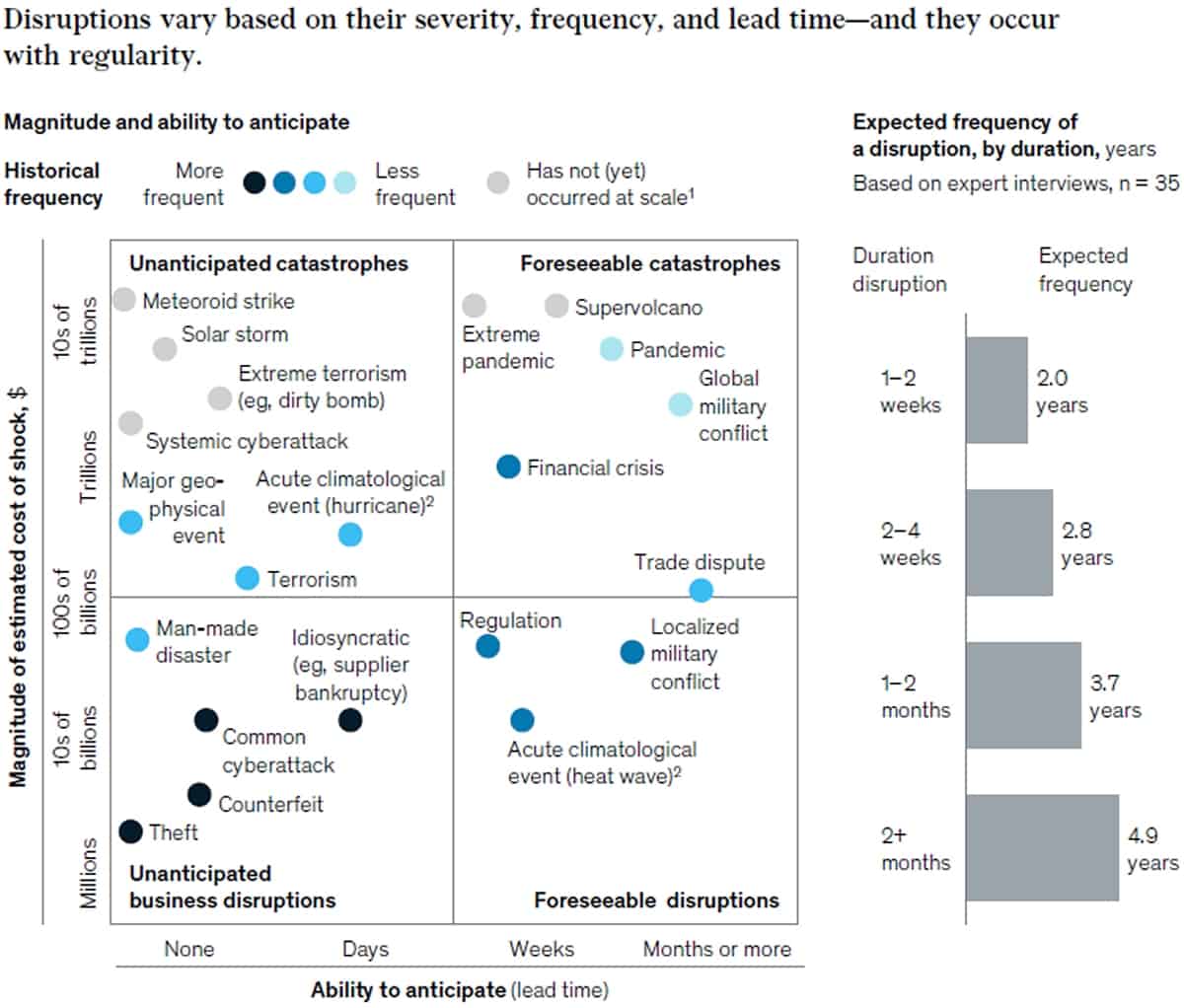

A central assertion of the MGI report is that “shocks that affect global production are growing more frequent and severe. Global flows and networks offer more ‘surface area’ for shocks to penetrate and damage to spread.”

MGI estimated that once each decade, disruptions could erase 40% of a year’s profits for some companies. Severe events occurring every five to seven years could erase almost an entire year’s profits for companies in some industries.

The researchers applied risk analytics to a list of events that call to mind the Book of Revelation or Yeats’ “The Second Coming” (“Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold. Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world …”).

Lead times of super-volcanoes were plotted against dirty bombs; cost magnitudes of meteoroid strikes and solar storms were weighed against fallout from cyberattacks and heat waves.

The MGI team began this project last year, before the outbreak. Suddenly, right in the middle of the research, one of the dots on the risk chart was no longer hypothetical. A dot at the upper end of the “magnitude of estimated cost” scale — in the “tens of trillions” zone.

Coronavirus “is a tragedy but also a call to action in terms of thinking about the resiliency issue,” said Barriball. The outbreak will be a tipping point, moving more companies to act, he believes.

A McKinsey survey conducted in May found that 93% of respondants plan to increase resilience. Top strategies were dual sourcing of raw materials (53%), higher inventories (47%), nearshoring (40%) and regionalizing supply chains (38%).

All of these cargo strategies have implications for ocean shipping, from bulk transport of oil and ore to containerized transport of textiles and electronics.

Bulk shipping: Appetite for destruction

Vessel demand is not measured in cargo volume, but rather, in “ton-miles”: volume multiplied by distance.

In bulk shipping, which accounts for the majority of ocean volumes, the longer the average voyage length, the more ships are occupied, the less ships are available to bid on the next spot contract, and the higher the spot freight rates.

Disruptions such as geopolitical conflicts and severe weather often force bulk ships to take longer routes, or tie ships up, causing spot rates to spike.

Decades ago, fortunes were made when the Suez Canal closed and tankers had to circumvent Africa: Think Aristotle Onassis.

Rates spiked last fall when tanker attacks in the Middle East spurred Asian importers to bring imports forward and tap Atlantic Basin supplies further afield.

As BIMCO’s Peter Sand told FreightWaves in a recent interview, “If you’re a tanker owner, you beg for geopolitical instability.”

Barriball offered words of caution on this mindset. “If someone is looking at this report and saying that shocks are good for my business and this is a positive, they may not be thinking about the problems from all the angles they need to be. They are not appreciating that if shocks are bad enough, volumes won’t be on those routes anymore.”

Indeed, shocks and catastrophic events that affect the demand side of the equation can reduce ton-miles. Case in point: the initial collapse in oil demand due to coronavirus lockdowns.

Container shipping: demand and supply fallout

Demand collapses from global shocks have the same negative effect on container shipping as in bulk shipping. But for container shipping, fallout is compounded by the fact that box carriers have scheduled service.

Bulk shipping is a “tramp” model. The ships go where they have to go, when there’s a load to carry. In container shipping, carriers provide “liner” services on designated routes at designated times. When transport demand collapses, carriers “blank” (cancel) some sailings — as they did at the height of the coronavirus crisis. But even so, most ships still sail.

Depressed utilization brings in less revenue to cover fixed costs such as crew and debt service for owned ships. For leased ships, there’s less revenue to cover charter payments.

A key focus of the MGI report is how the threat of ongoing shocks could change shipper supply chains in the years ahead.

How these changes play out will have major effects on ocean shipping. Particularly so for the scheduled services of container lines that are, by nature, far less nimble than the tramp bulkers.

Regionalization and box-ship size

The container shipping industry built its fleet for extreme globalization, with a focus on giant ships with capacity to carry 15,000 twenty-foot equivalent units (TEUs) or more. Owners build these ships for extra-long-haul, Pacific-to-Atlantic Basin runs, primarily the Asia-Europe trade.

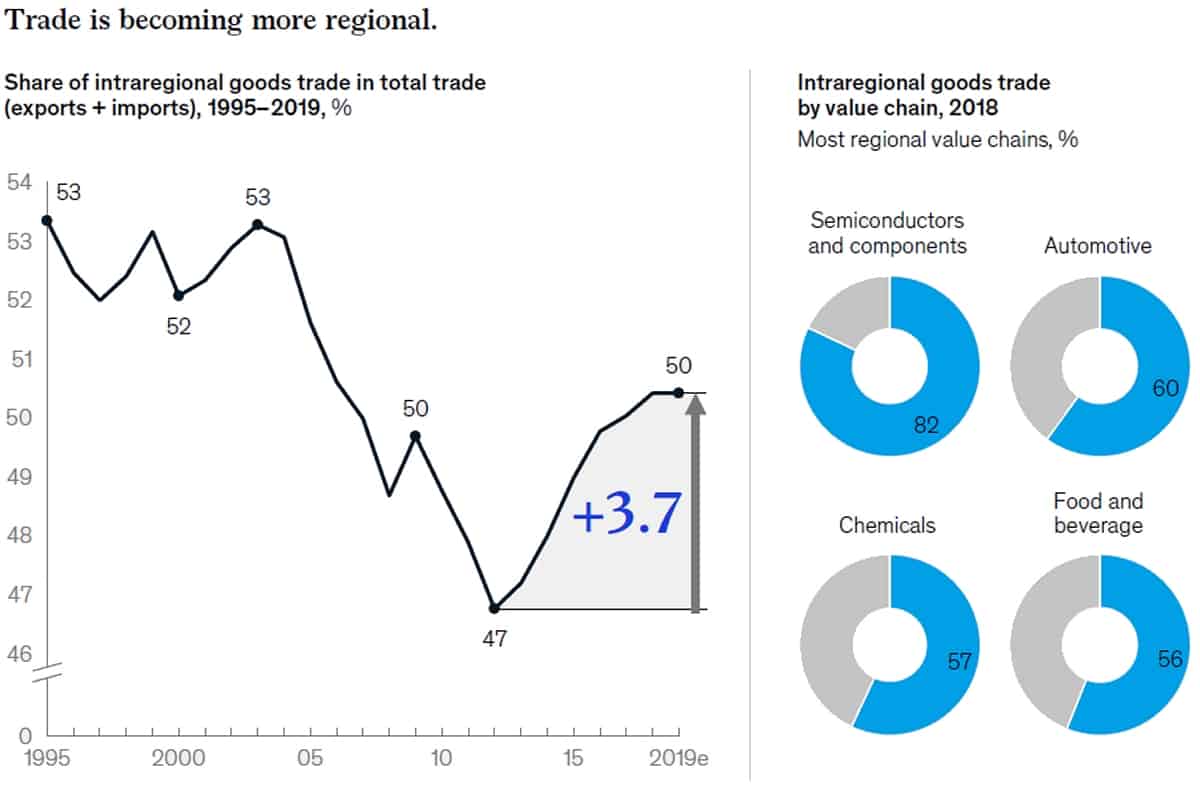

The more trade becomes intraregional as opposed to basin-to-basin, the less the global container-ship fleet fits reality.

Industry guru Martin Stopford, non-executive president of Clarksons Research Services, said earlier this year that “we might be entering into an era when globalization is no longer the [driving] issue, so we may be looking at more short-sea shipping and more regional clusters.” There will be less demand for ultra-large container ships, he predicted.

BIMCO’s Sand said told FreightWaves: “Once the ships are built, they’re sailing for 20 years. There’s no relief from those mistakes. And this whole trend of supersizing trade lanes and putting ultra-large container ships in place from one hub to the next will be challenged. You just cannot call at 10 ports with an ultra-large container ship. That is simply not efficient.”

More regionalization means that carriers would need more medium-sized ships to serve multiple hubs, and more smaller feeder ships — and the MGI report points to more regionalization ahead.

Regionalization and resilience

“Regionalization is ongoing,” explained Barriball. “You saw intraregional trade go from 47% in 2012 to about 50% [in 2019]. For freight carriers in long-distance global trades, it would be prudent to start thinking about scenarios where we come out of COVID and see even more regionalization of supply chains.”

The ocean shipping aspect of the supply chain has proved highly resilient in the COVID crisis, raising the question of why shippers see regionalization and shorter ocean transits as a defense against disruptions.

Barriball responded, “It comes in two different flavors: one upside flavor and one risk-mitigation flavor. On the upside, having things closer is desirable, as we saw in recent years with ‘fast fashion,’ where someone wears something and suddenly everybody wants it and companies are able to rapidly churn it out. It’s the same across a lot of consumer products.

“The desire to be closer to the consumer has nothing to do with the performance of ocean carriers. It’s about folks not wanting inventory tied up on the ocean for a few weeks.”

Global disruptions can quickly change the kind of products consumers want, which means shippers need to respond quickly. “It’s about being more agile. The most recent example you’ve seen is toilet paper and manufacturers switching over lines of household paper to toilet paper.”

The best example of the downside-risk argument for regionalization arose from the Japanese tsunami in 2011. “Automakers were some of the first to move towards more regionalization because of the tsunami,” recounted Barriball.

“They realized how much critical production they had in Japan and the tsunami actually shut down assembly lines globally. They decided: When affordable, let’s have regional production for critical commodities so if this happens again, we don’t experience a global disruption.”

Rising inventories could boost shipping demand

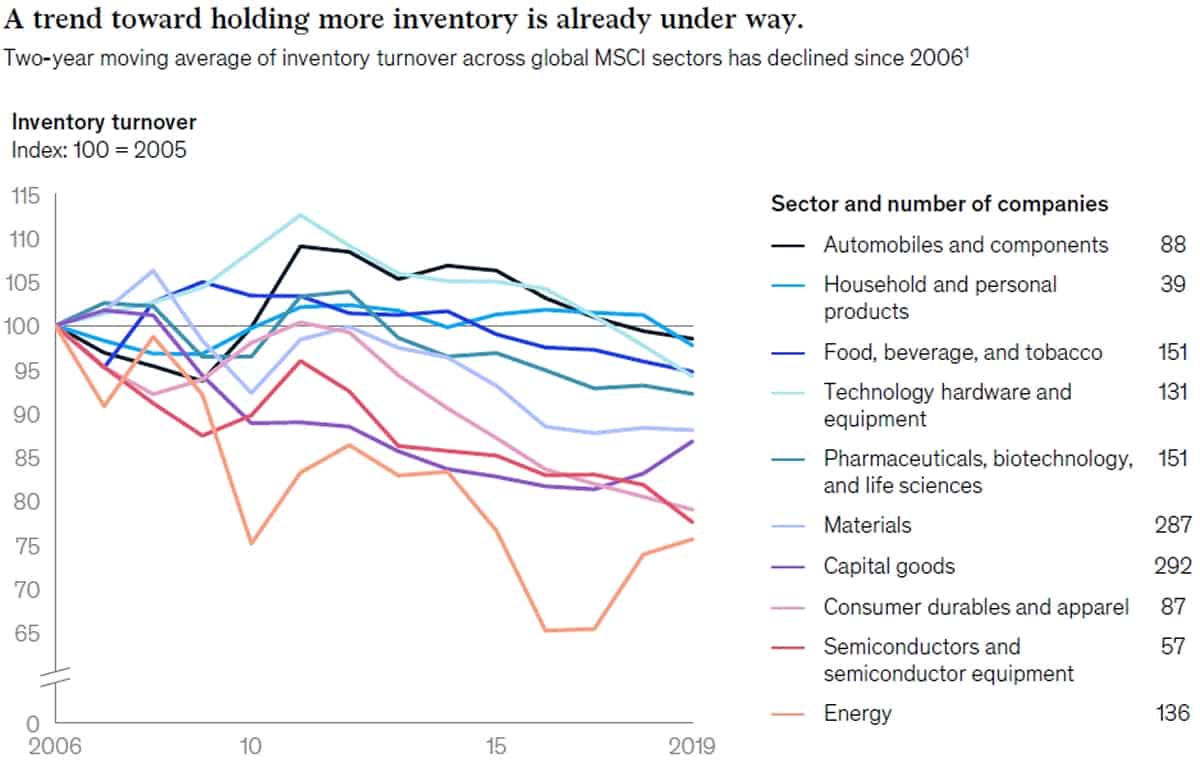

Another U.S. importer strategy to protect against global shocks is to increase inventory levels. A change in strategy toward higher inventory levels would lead to a short-term increase in inbound container volumes. Given flows from China to California over recent weeks, this transition might already be underway.

According to Barriball, “After COVID, I think there will be a divergence. Some industries will go more along the lines of the automotive industry, and say they will regionalize more, and some will hold more inventory.

“I do think that building more inventory of critical products is a lever — especially in the near to medium term — that executives are looking at. They’re looking at how to get through the uncertainty of what we’re experiencing right now. Over the longer term, beyond the next 12 to 18 months, I think the question of whether inventory levels will stay higher is not yet solved. And I don’t think there will be a one-size-fits-all answer.”

Digital transparency pays dividends

Regardless of where U.S. importers stand on regionalization versus higher inventory, the threat of supply chain shocks could push them toward more transparency solutions.

Companies with high transparency have been able to move quickly in response to the coronavirus. “One example we talked about in the report is Nike,” said Barriball.

“In the first quarter, when China started shutting down, Nike was able to quickly understand what inventory they had in which brick-and-mortar locations and in which warehouses. They were able to rapidly reposition that inventory for online sales.

“The sales team was able to figure out which orders they would not be able to sell, and to stop them, and then push the marketing team on what they could sell. As a result, they suffered a much lower sales decline than their competitors.

“This is a moment where executives say: What can I do in a timeline not of months and years but of days and weeks to stitch together data from multiple places to get transparency on where things are that are coming from China, or wherever they’re sourcing from? How are they getting to the container ships to the ports to the trucks or the train to the stores? Very few companies have that transparency. The ones that do have it are going to do better during a crisis.

“This crisis has really motivated people to look more at digital. Logistics has been ripe for more impact from digital and AI for a long time. A lot of companies haven’t fully embraced it yet for a lot of good reasons, but I think it’s now showing its value.

“Our report found that that the frequency of shocks is increasing — whether it’s cyberattacks, geopolitical issues or a range of others — and one might reasonably expect them to continue to increase. So, we really think that this is the time it makes sense to do this [invest in digital transparency].”

Headwinds for change

Of course, the cynic would respond: We’ve heard all this before, but change has been slow. If company decision-makers are salaried executives, not owners, they may focus on the short-term incentives. Such executives may conclude that changing global supply chains, increasing inventory costs and investing in transparency solutions could lower short-term returns to their personal detriment, even if it’s to their company’s long-term advantage.

Asked about the headwind of “short-termism,” Barriball responded, “It’s a fascinating question. I think the answer is that there are responsibilities for three different parties. First, you need companies to appreciate the value of resilience and incorporate that into executive performance, and measure resilience just like you measure growth.

“Second, you need investors to understand the value of resilience and hold management teams accountable. Otherwise, you might end up with a race to the bottom.

“And third, you need customers — both business customers and retail customers that experience the effects of disruptions — to really start asking questions about resilience.

“These three parties really need to work together to increase the overall resilience of value chains. And the message we have, for executives in particular, is that resilience isn’t a trade-off. We don’t think being more resilient is being more costly. We think you can be both more resilient and more productive, and digital transparency is a great place to start.” Click for more FreightWaves/American Shipper articles by Greg Miller

MORE IN-DEPTH FEATURES ON THE GLOBAL SUPPLY CHAIN: Q&A with BIMCO shipping analyst Peter Sand: see story here. Shipping guru Martin Stopford sees less globalization, more tech: see story here. Q&A with IHS Markit’s Paul Bingham on how the virus will impact the global supply chain: see story here.