Differences remain in what is best path for drivers to follow, but all agree that port congestion is a problem that needs fixing.

The Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are among the best in the nation for freight demand as FreightWaves’ SONAR platform has shown. But according to some, they are the worse places for drivers to work.

The issue came up this week as drayage drivers, warehouse workers, union organizers, and their supporters walked picket lines in Southern California, the 16th such action in five years.

The event did not significantly impact container operations in the region. But even as tight labor creates a driver’s market, some Southern California drivers remain dissatisfied and ready to walk off, potentially putting one of the nation’s most vital supply chains at risk.

While testifying before the Los Angeles City Council, Gene Seroka, executive director of the Port of Los Angeles, was asked whether labor disputes impacted shipper decisions as to where they route their cargo.

The answer is “no,” Seroka said. But he acknowledged that there are other ports that could attract containers should port disruptions raise concerns.

Container volumes through the Port of Los Angeles reached 9.1 million twenty foot equivalent unit (teus) in their fiscal 2017 year. That was down 1.1 percent from a year earlier. And the volumes for the first half of 2018 are down close to 4 percent from the year earlier period.

Over the same time, the Port of Long Beach saw container volume reach 8 million teus, nearly 16 percent higher than a year ago.

“What I can say is that beneficial cargo owners will pivot and adjust based on what is happening in and around the harbor,” Seroka said. “Other arrangements will be made.”

As for the week’s protests, Seroka did not take sides in the issue. But he thanked the city council and the Teamster organizers for “shining a light on a part of our business that needs to be improved greatly.”

The Teamsters said the strikes involved Southern California drayage drivers for XPO Logistics (NYSE: XPO) and privately held, third-party logistics provider NFI Industries.

Barb Maynard, a spokeswoman for the local Teamsters 848, said this week that protests occurred outside of XPO warehouse in Los Angeles and San Diego, and outside a NFI-owned warehouse near the Port of Los Angeles.

The strikes were peaceful, but 60 people were arrested at a civil disobedience rally at a local park on the last scheduled day of the protests.

The size of the action was unclear. One source estimated that NFI employs about 150 to 200 drivers, while XPO employs about 250. But the Teamsters says about 1,000 drivers at both companies have been classified as independent, which has been at the heart of the disputes.

Maynard was not able to determine the number of drivers striking during the week. But she says the actions were slowing movements around the nation’s busiest ports, and forcing shippers to switch carrier plans.

“What we’ve heard is that at some terminals, If they can substitute the job out to someone else, they are doing that,” she said. But she said “the workers feel incredibly empowered by the action.”

The Teamsters took their protests to other targets as a new California gives drivers more leverage with motor carriers in pay disputes.

Next year, the Labor Contracting-Customer Liability law takes effect. The law requires shippers to “share with a labor contractor all civil legal responsibility and civil liability” for any disputes over payment of wages and workers’ compensation coverage.”

The Department of Industrial Relations says 987 drivers have filed wage and other disputes between 2011 and 2018, winning 451 of those cases for $48.3 million.

Numerous companies other than XPO and NFI are named in those disputes. But in many instances, NFI and XPO are the successor companies

Maynard said protests also occurred at Amazon’s (NASDAQ: AMZN) Moreno Valley warehouse and at international miner Rio Tinto’s (NYSE: RIO) facility in Boron, California. Protests were also said to have occurred at the Union Pacific (NYSE: UNP) operated Intermodal Container Transfer Facility and the LATC near downtown. Los Angeles.

The Teamsters took the protests to customers because “they are turning a blind eye to their supply chain,” Maynard said.

Maynard admits some of the problem is structural as the industry remains intensely fragmented. Some 600 listed carriers employ somewhere between 12,000 and 17,000 drivers in the Southern California market.

Carriers say the Teamsters push the strikes in order to add members. But Maynard says its only interest is in seeing more drivers classified as employees so “they would have basic workplace protections they do not presently have.”

She says the misclassification of drivers results in unjustified expenses being taken from drivers’ paychecks and other instances of wage dispute.

“What we are fighting for is them to be properly classified so they can get disability insurance, they can get workers’ compensation,” Maynard said. “Once they are employees, it’s entirely up to the companies what to pay them.”

Day 3 #Portstrike at @NFIindustries whose customers include @amazon @Lowes @RTBorates – We are ALL Employees!! pic.twitter.com/rSa1OYft1J

— Justice4PortDrivers! (@PortDriverUnion) October 3, 2018

But Weston LaBar, chief executive officer of the Harbor Trucking Association disputes the idea that the end goal for most drivers is to be an employee. LaBar says about 80 percent of the 17,000 drivers registered to work in the Ports are independent owner operators, with the rest employees.

“Driver morale is at an all time high,” LaBar said. “If there was a such big push for an employee model, why wouldn’t the ratio be the other way?”

He says drivers typically start out as employees at motor carriers, but decide to become owner-operators as they find shipper accounts that the motor carrier does not want to take.

“Within 12 months, many employees become an independent contractor because they want to make their own hours and business,” LaBar said. “They find a furniture store that just needs to ship three containers a month.”

LaBar says the head of one unidentified local carrier told his drivers that the company would go to an employee model to avoid regulatory risk. But nearly two-thirds of the drivers then left, LaBar says.

LaBar says independent contractors can make up $65 per hour, depending on the number of hours worked and routes served. It was not clear if that wage is net of operating expenses.

Employee drivers can make between $17 and $27 per hour. An online ad for XPO listed driver positions starting at $22 per hour.

LaBar says many drivers are “able to make six figures annually” through the owner-operator model.

But owner-operators, along with the entire market faces ongoing risk. The Ports continue to push new environmental regulations on trucking companies. This month, any new trucks registered to work in the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach are required to be model year 2014 or newer.

Demand may also change with new projects. The Port of Long Beach okayed an $870 million budget for an on-dock rail project which aims to take trucks off the road. The Port of Los Angeles and BNSF continue to work toward developing the near-dock intermodal yard Southern California International Gateway.

The one issue that all sides agree on is improving port efficiency. Port of Los Angeles’ Seroka says turn times are very important for both employee and owner-operator drivers.

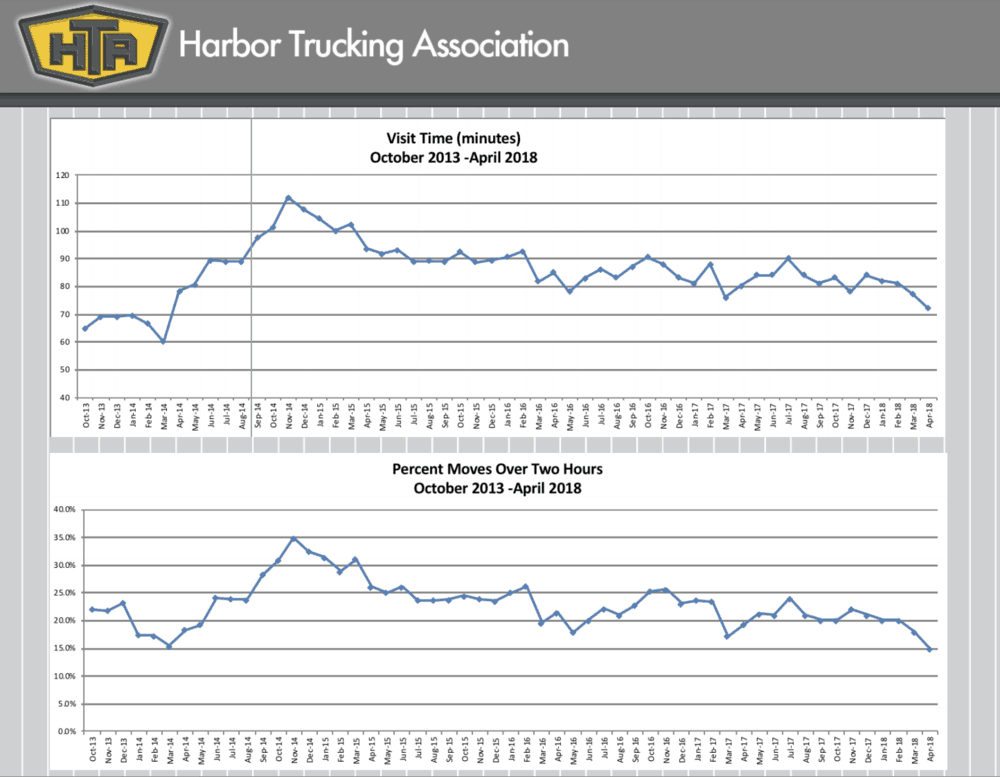

He says the Port of Los Angeles’ turn times average 87 minutes, “which is among the worst in the nation.”

“We must improve the visiting process for the drivers so they can bring their cargo to and from our facility in an expeditious fashion, Seroka said. “That helps with how much money they make and the types of companies that we attract to this port complex.”

The HTA said that average turns at both ports was 82 minutes in September. That is slighly worse than the 72 minute turn-time it saw in April. LaBar says turn times have decreased sharply from the levels seen during the start of the West Coast port strikes, but still remain elevated compared to periods prior to 2014.

“Turn times have gotten better,” LaBar said. But Port of Los Angeles remains the longest turn at 90 minutes compared to the 70 minute turn at Port of Long Beach.

Much like drayage, the fragmentation of the ocean shipping business is causing its own problems. LaBar says the change from an integrated ocean shipping business to one where there are separate terminal owners, chassis pools, and motor carriers has also reduced efficiency. LaBar says the ocean carriers’ push for larger shippers discharging more containers in less time has caused problems for surface transportation.

Terminals are also refusing to allow drivers to drop off empty containers at where they pick up loaded containers, instead requiring that they be dropped off at another terminal. Those moves through the port can mean additional higher turn times, LaBar says.

“Shippers, carriers and terminals don’t like missed appointments,” LaBar said. “But it’s the ocean carriers that are causing the missed appointments.”

“I blame the ocean carriers,” he said. “They made the most selfish decisions. It’s all about turning the ship as fast as possible.”

Turn times continue to vary by terminal. Among international ocean carriers, the Orient Overseas International-owned Long Beach Container Terminal remains the standout due to the high level of automation at the facility. The LBCT, which primarily serves the CMA CGM-controlled Ocean Alliance, sees turn times under 40 minutes.

Depending on destination distance, that turn time allows a drayage driver to make between three and five turns a day.

But other ocean alliances are seeing much worse turn times. The International Transportation Service terminal, which serves the Ocean Network Express, the alliance of Japan’s major carrier,s saw turn times over 80 minutes.

The 2M Alliance-controlled Total Terminals International saw turn times drop from 100 mintues last year to near 80 minutes this year.

The disparities at the terminals echo down to chassis where drivers face imbalances, LaBar said. A driver having to get a chassis from a pool, rather than bringing their own, can face an additional half hour of turn time or more.

But the port continues to make improvements. LaBar says the Nippon Yusen Kabushiki Kaisha and Macquarie Infrastructure Partners-owned Yusen Terminals in the Port of Los Angeles has stood out for improving its appointment systems. London-based Voyage Control is providing the software and integration for Yusen Terminals.

LaBar was also optimistic about the GE Port Optimizer project which aims to integrate the disparate software systems at the port through APIs into a common interface easily available to motor carriers.

“We feel like GE Port Optimizer is a game changer,” LaBar said. “The more visibility into the different silos at the port is more opportunity for everybody.”

Maynard of the Teamsters agrees that any initiative to improve port congestion would be welcome among the drivers.

The Ports “are a mess,” she said.