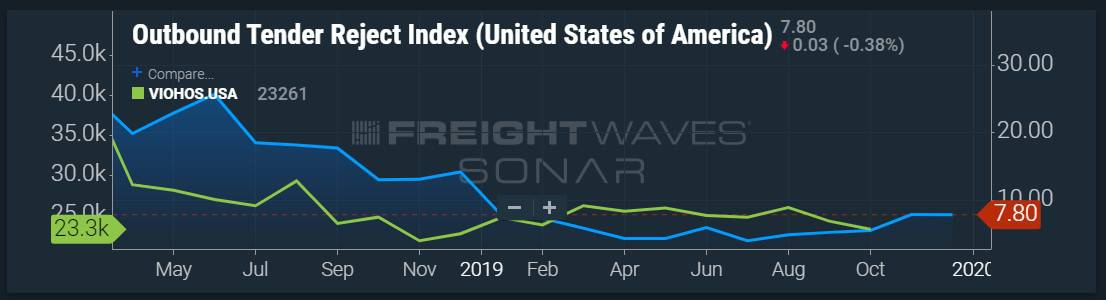

When electronic logging devices (ELDs) became the law of the land in the United States two years ago, trucking rates edged up as capacity left the market after drivers used to cheating the system were sidelined by stricter enforcement of hours-of-service rules.

But the federal Drug & Alcohol Clearinghouse, set to launch on Jan. 6, will have an even greater effect on capacity, according to top industry executives, because of the number of drivers who will no longer be eligible for a job.

“I think a 3% capacity reduction within the first six months of the year is realistic and will have a material impact on what the supply-demand dynamic looks like in 2020,” Derek Leathers, president and CEO of Werner Enterprises [NASDAQ: WERN], told FreightWaves.

“A winter storm that lasts one or two days and covers a four- to five-state area is plenty big enough to cause capacity constraints that ripple through the entire network and take multiple weeks to work out of. So even at a time where capacity has been looser in 2019 than in 2018, it is still within a point or two of equilibrium. And it doesn’t take much to affect that balance.”

The clearinghouse, to be administered by the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA), will close a loophole that currently allows drivers who are fired for failing a drug test to get hired by another trucking company by lying about failing the test. Driver consent records will be retained in the database for three years, which means it will take at least that long to fully populate the system. Once that happens, the industry could see an even bigger shakeout.

“It won’t be a Day One [capacity] fallout, but once [the clearinghouse] gets populated, I think you’re going to have up to 10% of the driver population being excluded” based on current drug test failure rates, predicted Eric Fuller, president and CEO of U.S. Xpress [NYSE: USX].

“That’s not only going to affect the current pool of drivers, but also greatly minimize the pool of people available to come into the industry. So there’s going to be some significant headwinds on a go-forward basis as it relates to getting the numbers of drivers that we need in our market. But we also don’t need someone actively using drugs driving an 80,000-pound truck down the road at 65 mph.”

While he agrees that the FMCSA clearinghouse will likely have an even bigger effect on trucking capacity as did ELDs, Dean Newell, vice president of safety and training at Maverick Transportation, also views the new regime as a positive for safety.

“I think it’s probably going to take people off the road, so from a capacity standpoint I think there could be more trucks sitting empty,” Newell said. “But it’s also going to make it much more difficult to hide” positive test results, he said.

Unseated trucks

While trucking rates tend to shift upward when capacity exits the market – a good thing for carriers – there’s a downside to having cabs sitting idle. “The cost of equipment is more expensive than ever, and if you have unseated tractors, it’s difficult to survive for very long,” Leathers said. “Depreciation doesn’t stop, and the bills don’t stop coming in for that equipment.”

Fuller pointed out that to avoid the expense of unseated trucks, many carriers will resort to hauling inferior freight or participating in less desirable lanes. “The next step would be to sell that piece of equipment to avoid that fixed cost,” he said. “Strategically you wouldn’t see a lot of people parking trucks and keeping them in their fleet. They’d want to divest of them or do whatever they had to do to keep that truck operating and producing revenue.”

Enforcement snag?

To give state motor vehicle agencies more time to work out how their IT systems will interact securely with the clearinghouse to ensure privacy, the FMCSA recently extended the compliance date for state agencies by three years, until Jan. 6, 2023.

“The compliance date extension allows FMCSA the time needed to complete its work on a forthcoming rulemaking to address the states’ use of driver-specific information from the clearinghouse and time to develop the information technology platform through which states will electronically request and receive clearinghouse information,” the agency affirmed in its Dec. 12 rulemaking.

But Dave Osiecki, president and CEO of Scopelitis Transportation Consulting, cautioned that delaying the deadline for state agencies weakens the ability of the clearinghouse to be effectively enforced – which could mitigate the constricting effect on capacity.

“There are three enforcement mechanisms with regard to the clearinghouse – the employer, law enforcement using roadside checks, and the state law enforcement agencies,” Osiecki told FreightWaves. “If the state agencies aren’t part of the equation, it becomes, for the most part, an industry-based enforcement system. The state agencies are a major cog in the wheel, and when that’s taken out, the wheel doesn’t turn as smoothly as it should.”

The hair-test effect

Industry executives emphasize that an even larger capacity shakeout is lurking – the effects of which could begin as early as the fourth quarter of 2020 – once hair testing becomes a federal requirement.

A survey released earlier this year by the Trucking Alliance (of which U.S. Xpress is a member) projected with a 99% confidence level that more than 300,000 truck drivers currently on the road would fail or refuse a hair analysis, effectively knocking them out of industry.

David Heller, vice president of government affairs for the Truckload Carriers Association, considers a 10% hit on capacity using hair testing “fairly conservative and has the potential to be higher, considering what some of the fleets that already are using hair testing have reported,” he said.

Draft guidelines for government-wide hair testing “have been distributed to all federal agencies for a second round of comment and review, and the length of time for review will be determined by the Office of Management and Budget,” the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services confirmed in early December. After OMB approval, the FMCSA would be required to propose a rulemaking on how a hair testing regime would apply to motor carriers.

Filling the driver gap

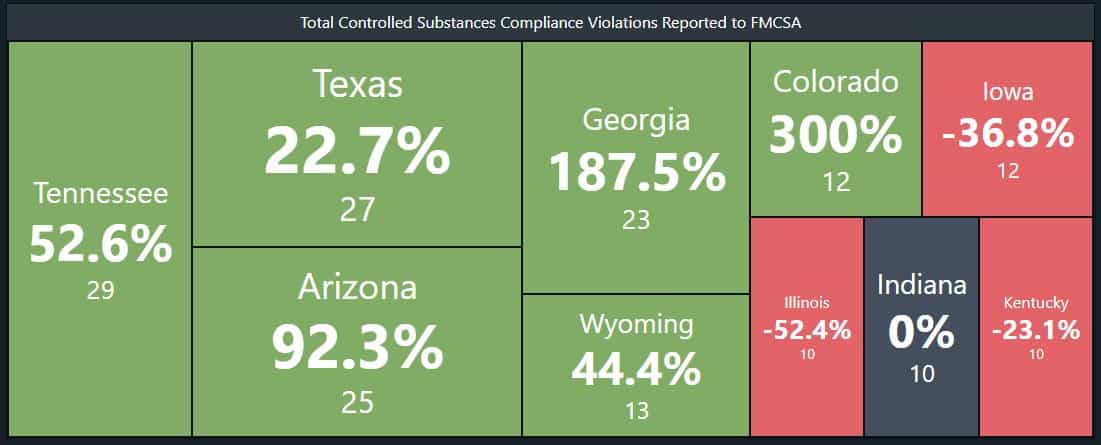

The American Trucking Associations (ATA) stepped up efforts this year to crack down on drug use in the trucking industry, particularly marijuana and opioids, by creating a Controlled Substances, Health and Wellness subcommittee, with the goal of better informing lawmakers and regulators about the safety implications of drug use on the nation’s highways.

A big proponent of hair testing, ATA President Chris Spear acknowledges the effect on trucking capacity if hair testing were to be incorporated into the Drug & Alcohol Clearinghouse.

“That’s why I think being able to hire under-21 drivers is extraordinarily important,” Spear said. “Driver retention is important. Urban hiring is important. Veteran and existing military service people is important. These are all key things we need to be doing collectively in order to supplement the effects of the clearinghouse. I’m not too concerned about the capacity question so long as we’re doing these other things.”

The carriers least concerned about a capacity shakeout once the FMCSA’s clearinghouse gets rolling are those that have already put themselves in position to take advantage of the supply-demand changes that the new system is expected to bring.

“You have to have your trucks seated and ready and then realize the opportunity for rate relief that is required and needed right now,” Leathers emphasized. “Those will be the companies that will come out winners.”

Daniel Kennedy

All transportation has had random testing. Also 25 years ago some folic testing was used as a defense if a random was taken to court. Transportation workers are unique in that we should value our sobriety while working! If our society has become so irresponsible as to think one can get away with a spot check then the person does not deserve to be in our industry.

James Darton

It’s not drugs that’s the problem you’re using it as a smoke screen. The problem is the fast tracking an undertrained person into a cmv to fill the seats of all the equipment the mega carriers have . Even to the point of putting the motoring public in great danger. You can’t fast track safety. The fruits of your labor is showing it’s self look at the massive pile ups ,drivers Operating in adverse weather when they should have been parked. Proper training that driver would have known weather it was safe to drive or not. I see first hand what you’re up to one day it’s going to be your love ones in front of one of those undertrained drivers in freezing fog.

Chet Manly

Let’s see, the 2 acceptable vices are cigarettes and alcohol. Both known to cause a multitude of ailments. Yet marijuana, becoming legalized and prescribed in more states every year, is still a death sentence for a driver. Wtf. It’s ok to park the truck and pound the sauce on my ten, but a joint after a stressful day is criminal. The hypocrisy knows no bounds. Political bullshit.

Noble1

HEY ! Don’t do drugs , politicians hate competition .

GOOGLE IT !

politicians caught with drugs

And most behind the wheel don’t do drugs , they smuggle them in , LOL !

Quote :

Trucking co. owner arrested for allegedly using business to traffic drugs

“The owner of an Orlando, Fla.-based trucking company has been arrested and charged in connection with allegedly using his trucking business to haul large quantities of marijuana and cocaine into Florida from other parts of the country.”

November 28 2019

UPS workers ran massive drug shipment operation for a decade, police say

So , drivers and carriers don’t necessarily do drugs , they smuggle them , LOL !

Who is to “prevent” the pencil pushers behind the desks whether they are in politics creating ignorant laws etc , from being on or involved with drugs ?

And what about the “other” motorists” ???

In my humble opinion …………

Sandra

The drug test is the best thing DOT can start doing, but….drinking on your time off is your right as an American. But….if you still have alcohol in your system when you get behind the wheel, you can be tested and fail.No one wants people who are drinking or doing drugs behind the wheel of any kind. With a hair test….these companies will get the better drivers, but the clocks are causing alot of problems. Drivers are dying from stress and heart attacks because these companies are still using forced dispatch. They can go in and fix a clock from the office and expect a driver to keep driving when he should be sleeping. So what good are these stupid computers? They aren’t worth a shit. There is still alot of illegal driving on the road. GET REAL, COMPUTERS ARE A JOKE

Mike

Shakeout? Hardly, they will just import more foreigners. There is no shortage of anything out here…

Operating authority is handed out like candy at Halloween to any and all that apply. Imported drivers, who cannot even pass a written exam in English, easily obtain their CDL. The foreign owned companies 1099 the drivers, and run their operations from overseas, pick your continent. They have no skin in the game, and routinely cheat the system.

We need REAL regulations, not ridiculous regulations that punish the driver, but regulations to get this industry back to a semblance of sanity. They can start with enforcing the rules requiring drivers speak and read English. Then they can make it difficult to obtain operating authority, how about you have to be a naturally born US citizen to obtain and pass a stringent background check as well as being deemed financially strong enough to weather a few storms? Would this not fit in well with our national security initiatives?

Sure, a few will be weeded out, and more experienced drivers will hang it up. The only winners in all of this are the insurance companies and the drug clearing houses/labs. Follow the money. No different than the Sleep Apnea scam.

Rick

Well said Mike. Just thinking out loud, can you use your arm or leg hair to test if someone is bald, or shaves their head?

Mike

They cut hair off my chest once, I had a crew cut, but I always do. Any body hair will do.

Noble1

Quote :

” There is no shortage of anything out here…”

Oh yes there is . There is an enormous shortage of developed brain cells & ethics in this industry .

I challenge you to refute my statement . LOL ! (wink)

In my humble opinion ……………….